Images of Lucknow

Roshan Taqui (ed)

Taqui, Roshan (ed);

Images of Lucknow

New Royal Book Co., 2005, 192 pages

ISBN 8189267043, 9788189267049

topics: | history | lucknow

A collection of articles on the heritage of Lucknow, with the aim of trying to preserve more of the historical buildings and palaces. Based on a conference organized by the HARCA, an NGO, on Nov 15-16, 1998 at Lucknow.

HARCA, Historical and Archaeological Research and Conservation Agency, works for conservation and restoration of heritage buildings in Lucknow. Roshan Taqui, who specializes in the 1857 rebellion, is its secretary.

Taqui is also the author of "Lucknow 1857 - The Two Wars at Lucknow" (the second war was the recapture of the city amid a huge bloodbath in 1858). His grandfather and great-grandfather died in the rebellion.

I was not aware that a very large part of the city - between two-thirds to three-fourths of the central areas according to some contemporary authors - were demolished after its recapture. It appears that regiments from outside were brought in to implement the demolition :

All of a sudden the city demolition started. Typical type of excavators were they. Those madrasi men, negro faced, any type of walled ccnstruction and high rise building was excavated by them in three attacks -- even the foundation. Regiment after regiment came and razed to the ground the houses of the famous and popular persons using bull dozers. [Munshi Mendi Lal in Naunga, known as Maharba-e-ghadar) While this book is a treasure-trove of hard-to-find information, the editing is terrible, and lapses of english on every page indicate a very cavalier attitude towards quality. No doubt the authors and editors were hard-pressed to meet the deadlines of publishing, but such a large number of grammar and spelling errors are quite unacceptable in this digital age. They are particularly grating in the excellent lyrical essay by Nayyar Masud whose translate text could surely have done with some careful editing.Some of these articles have also appeared in other work. Thus, P.K. Ghosh's "Impact of The West in the Court of Avadh" is largely similar % to his "Impact of Europeans on the Court of Awadh" in "Region in Indian % History" (2008) ed. Pratap / Jafri; and Rosie Llewellyn-Jones "The Queen Mother's visit to England" has been reworked into her "Last King" (2014) elephant with howdah approaching gate of macchhi bhavan, painting by the daniell brothers, 1801. the entire complex is no longer there.

Excerpts

First Census of Lucknow (1857) : Roshan Taqui

This census counted the number of houses in each neighbourhood (mohalla)

and not the inhabitants. For each locality, it also identifies the level

of wealth, and also the religious groups.

The census numbers were published in the short-lived Urdu weekly, "Tilism

Lucknow". As we find out from the article by Iqbal Hussain (ch. 8), Tilism

was brought out every Friday from July 25 1856 till May 8 1857, right upto

the eve of the rebellion. It thus covered the period immediately after the

annexation of Oudh (Feb 1856) and the expulsion of Wajid Ali Shah. The

summaries provided by Hussain documents a widespread disaffection with the

English rulers.

[The journal was written in ornate and elegant Urdu, and is the first

Urdu "newspaper". It was edited by Maulvi Muhammad Yaqub Ansari (d.1903).

It is among the earliest papers outside Calcutta.]

The census results started appearing in the Tilism on 20 March, and the last

reports came out on May 1. However, it reported a count of houses only, and

not people.

The author of this article (Taqui) has extrapolated population figures by

assigning 5 per house for the poor sections and 10 per house for the richer

sections - giving an average of 8 per house.

The detailed mohalla-by-mohalla count is organized by police station (thAnA).

There are six thAnAs, of which the last, Chini Bazar, seems to have been

covered a bit cursorily. In the first five thAnAs, most mohallas

have a few dozen houses and only a few mohallas cross hundred houses.

Thus the average population per mohalla in the

first five are from a few hundreds to a thousand, with a very occasional

2-3K. However, the houses per mohalla for Chini Bazar is in the thousands,

resulting in many population entries of 28K, 20K, 32K, 40K, etc.

Here are the number of mohallas in each station and the population as

extrapolated by Taqui:

Kotwali (K) 84 72K

Daulatganj (D) 41 45K

Haidarganj Qadeem (H) 21 53K

Ambarganj (A) 29 33K

Wazirganj (W) 73 77K

Chini Bazar (C) 24 362K

------------------------------------

+ Floating population 50K

Total estimate: 7.0 Lakhs

The entries for each mohalla are accompanied by short descriptions of the

population in terms of wealth, and religion. A few sample entries:

count (pop) wealth remarks

K Bagghi Tola 50 All mahajans bankers

K Nal Darwaza 171 rich + mahajans kins of Nawabs

K Kagzi mohalla 65 Prosperous all faiths

K Bahmani Tola 26 middle level Hindu & Muslim

K Mahmood Nagar 77 middle level Muslim

K Moughal Pura 13 Wealthy Muslim

K Teela Naqab Akhas 25 middle Govt Servants

D Shiv Puri 276 12 wealthy, Hindu

rest poor

D Chaturiya Ghat 14 one royal house of Nawab

rest poor Ali Naqi Khan

D Chamari Tola 75 poor chamar and Teli

D Chikwa Tola 53 half are wealthy qasai (butchers)

etc.

The enumeration may be more interesting from the point of view of

recreating these lost neighbourhoods.

As we learn from the chapter 3 (Nayyar Masood) and also ch 4 (M. Kaukab),

much of nawabi lucknow was viciously demolished during the years following

British re-occupation.

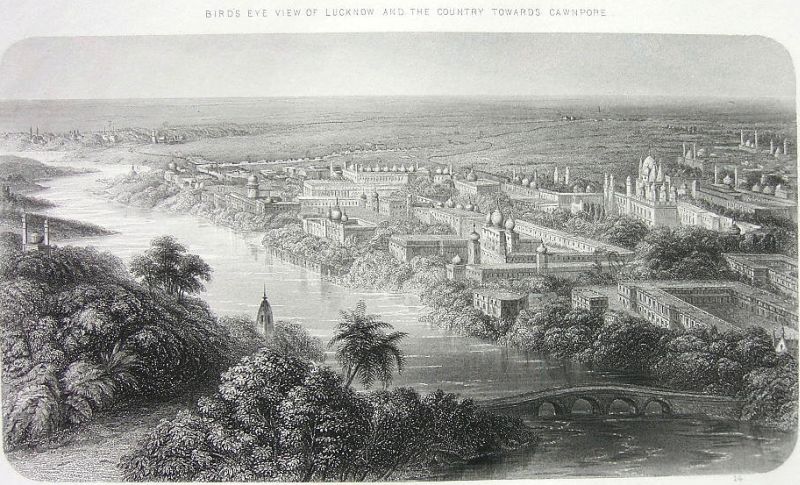

the impressive river-front of lucknow was almost completely razed.

the impressive river-front of lucknow was almost completely razed.

3 Nayyar Masood: Discovery of Lost Glory

Before we talk of preservation, [a] description of the destruction of this city by the English is necessary. After the war of 1857, they started demolition and without exaggeration, hundreds of inhabited localities (mohallas) and thousands of grand buildings had been razed to the ground. This act of demolition was started before the war when the area around the residency had been cleared by the British for tghe unhindered movement of their army. p. 39 Qaiser-ut-Tawareekh v.II, p.10: According to Kamal uddin Haider, sensing the war clouds looming large, the British officers in Machchhi Bhawan demolished the buildings nearby, and then in the periphery of the Residency... After the war, pro-English historian Munshi Mendi Lal stated: All of a sudden the city demolition started. Typical type of excavators were they. Those madrasi men, negro faced, any type of walled ccnstruction and high rise building was excavated by them in three attacks -- even the foundation. Regiment after regiment came and razed to the ground the houses of the famous and popular persons using bull dozers. [Naunga, known as Maharba-e-ghadar) Munshi Kalka Prasad Naheef: Thousands of palaces and worthy buildings came under the axe. [Rangeen bazaar-o-insha-e-Naheef] The dust from the razings was so thick that movement became difficult. After a short period, the map of the city had changed - entire localities vanished new roads were constructed over buildings. Even the old citizens found it difficult to reach their well-trodden destinations. Even in the poetry of Lucknow poets, the destruction became a theme. The famous poet Imdad Ali 'Bahar' (d.1878) wrote: luT gaye bashindgane lucknow ghar khud gaye khak uDAte hain bagoole khana-e-barbAd ke. the citizens of lucknow are now looted their houses dug up - winds blow the dust storm of (those) destroyed premises.] p.40 Late Dina Nath alias Husain Baksh "wajib" said in his poem: shAhon ke mahal gada ke ghar khudte hain darveshon ke atqia he ghar khudte hain, [was "khedte"] bande ka makAn khuda to kya wajib andher yeh hai khuda ke ghar khudte hain. [the palaces of kings (and) beggars are dug up The houses of saints and preachers are dug up If my house has been razed to the ground so what, The houses of God have not been spared. "Aneer Minai" the famous poet wrote these lines: ghar khudne ki poochho na museebat hum se, roti hai lipat lipat ke hasrat hum se, ya hum jAte the ghar se rukhsat ho kar ya ghar hota hai aaj rukhsat hum se. don't ask me the problem of house demolition desire weeps embracing us either we are going to have to leave the house or the house is going, leaving us behind. Mir Moonis told: hua ghar bhi azakhana bhi barbaad rahi baaqi mohalle ki na buniyad. not only residence but imambara is also destroyed - the very locality doesn't exist any more. Syed Mohammad Wazir (son of Mufti Mir Abbas) has written the couplet: masjiden khudti hain mutlaq bhi nahin jai namaz, hazrat isa hain ab parwardigar-e-lucknow woh saRak par gard uRti hai khaliq ki panah kor kar de chashme bina ko ghubar-e-lucknow. mosques were razed to the ground, there is no room for prayer. now christ is the god of lucknow. og god, there are such dense clouds of dust on the roads that would blind the sight of eyes. the statement is found are several places that three-fourth of the city has been razed to the ground during this action. "Qalaq" Lucknowi rhymed this: teen hisse se siva shahar khuda paya tamam jis taraf dekho nazar ata hai ek hoo ka muqam. more than three fourth of the city has been found excavated there is only desolation to be seen everywhere. the calculation is simple. half the city became the hunt of vengeance and one fourth the part of the roads, which were constructed in different parts of the city. A few names of loalities are also found in the demolished areas. For instance, Azmat Ali Kakorvi said: From near Aminabad to Shah Najaf to Beleguard (Residency) to Roomi gate, there was only desert like open land -- all the houses and low-lying areas were razed and the area made a dump. Half of the city of this area had been turned to rubble and dust till July / August 1858. The huge dargahs (tombs) of Shah Mina and Shah Peer Mohammad etc. came under the axe. Muraqqa-e-Khusrovi, p. 576 Kamal uddin Haider, the famous historian of the royal period, says: Right from the Residency to Dilkusha a wide road has been constructed aftger clearing the debris... Fifteen hundred feet around the fort (Machchhi Bhawan), ground has been leveled. Two roads from there are much widened... (Asifi) Imambara to Husainabad, all the houses and great localities fell under the radius of Fort Panch Mahala, Sangi Mahal, Hasan Manzil, etc. and other grand buildings, which came under 1500 feet of the fort, have been razed to the ground. Imambara Hasan Raza Khan, Masjid... bulldozed to the ground. Only tomb of Shah Mina left in Meena bazar. Other older graves passed into the radius of fort. Imambara Agha Baqar Khan demolished and levelled... houses that existed within the radius of the fort in the trans-Gomti area were also razed to the ground. Qaisar-Ul-Tawareekh, v.II, p. 354 Hakeem Mohammed Kazim has in his autobiography: There would have been no house left in the west and north of the city. All main markets - Ardali Bazar, Khayali Ganj, Ismailganj, Golaganj, Sitahti, Nabahra, Meena Bazar, Makaniya Tola, Shekhan Darwaza, Kaghzi Tola, Chandni Bazar, Thatheri Bazar, Johri Bazar, etc. have been demolished and levelled. The grand palaces of Haider Bagh and Machchi Bhawan, Kothi of Lala Guzari Mal Khazanchi (cashier), Panch Mahala and other beautiful buildings, which were constructed in lacs of rupees and all the royal palaces, excepting one or two, were razed. In short, two-third of the city was demolished and one-third was left, thousands of houses leveled in the construction of wide roads in this area. [auto-biography] People who had seen the thickly populated Lucknow of the royal period, termed this open city as desert. Most of the names of localities and buildings disappeared with the vanished historical sites. A few however, are left. Some of the photographs are also available. Some monuments like Chhatar Manzil, Chhota imambara, Asifi Imambara and Roomi gate etc are still existing, but most other monuments are in dilapidated condition - e.g. Satkhanda, Jama Masjid, Tomb of Hakeem Mehdi, Naubat Khana of Asifi Imambara, Darshan Bilas, Chhoti Chhatar Manzil, and so on. Concerted efforts are needed to preserve and maintain these buildings by the people who know better aboutt it. Some of the ruins - with the remains of walls and doors, minarets and stucco works, tell about its original grandeur. Now 3D pictures of these buildings can be created on computer.... Old photographers have painted a number of buildings of Lucknow. These include photographs of those buildings which are no more. the whole of the Qaisar Bagh, Lakhi Darwaza, Machchi Bhawan, Shekhan darwaza, Panch Mahala, begum koThi etc, can emerge before us with a little attention and expense. 43

4 Dar-e-Daulat : M. Kaukab

"Dar-e-Daulat" by M. Kaukab uses a famed gate to speak of the destruction of Lucknow post-mutiny. Where was this gate located? Today, a door standing near the Kaiserbagh complex is sometimes called Dar-e-Daulat and sometimes Sher Darwaza. Kaukab shows that the original Dar-e-Daulat had been a far loftier structure, and that elephants could pass through with passengers on their howdahs. it is today completely lost. Kaukab suggests that perhaps it was destroyed because it was from above this gate that some snipers had shot the infamous General Neill, sometimes called the butcher of 1857 for his savage killing of sepoys and indians, along his route. Kaukab feels that the gateway that remains is the one under which Neill died, which has a plaque commemorating the event (possibly it was spared owing to this). Dar-e-Daulat he guesses, must have been on a completely different wall, in the extensive Kaiserbagh compound. probably overlooking this existing doorway.

Munshi Nawal Kishore

Munshi Nawal Kishore As an aside, kaukab refers to Munshi Nawal Kishore in vehemently negative terms, calling him a traitor and his prose as deliberately not mentioning features of Lucknow since they may hold unpleasant echoes for the English masters... I had always thought that Munshi Naval Kishore was one of the more respected figures in Urdu publishing, but it seems that his success largely owed to his loyalty to the British. The India Govt issued a stamp honouring him in 1970, and he continues to be lauded in the media today.

from other sites: A Journey through Kaiserbagh

http://www.tornosindia.com/article_copy%2816%29.php [This is a detailed description of the extensive royal complex at Kaiserbagh, and its destruction in 1858-59.] After the siege it had become clear to the British military that large palace complexes such as Kaiserbagh, mosques, and big kothis must be seized and demolished since they provided convenient shelter to the enemy Indian forces. A letter from the Secretary of the Chief Commission to the Commissioner of Oudh clearly talked about wreaking vengeance: It is not by an indiscriminate massacre of the wretched sepoys that we should avenge our kindred. [instead, the city of Lucknow would be destroyed so that the] "mutineers were taught a lesson... No mosque - no temple should be spared." Another letter stated that, "As to Buildings in Lucknow, the only one that I think it might be well to level to the Ground is the Kaiserbagh as that is the palace where our chief enemies have resided during the rebellion." The death sentence was thus passed over Kaiserbagh. The work of reshaping the unhealthy and indefensible city of Lucknow was given to Colonel Robert Napier of the Bengal Engineers. He produced a document known as the 'Memorandum on the Military Occupation of the City of Lucknow,' dated 26 March 1858. Therein he proposed to open broad streets through the city and to demolish any enclosures not required for military purposes. Anything that came in the path of the proposed road was demolished. As a result, Kaiserbagh was slowly demolished and had wide streets passing through its main courtyards. The whole of the southern wall was demolished together with the Chaulakhi Kothi. Gradually the freestanding buildings inside the Kaiserbagh were demolished. Slowly the northern walls of the Kaiserbagh also vanished. Some enclosures became weak and collapsed as a result of structural instability. The passageways between Kaiserbagh and Chattar Manzil disappeared with the exception of Sher Darwaza. This gate had an emotive significance for the British because one of the relieving officers died under the gate and it was renamed Neil's gate after him. The tombs were stripped off their enclosures and they stood starkly by themselves. Kaiser Pasand was denuded of its upper storeys. No other building of Lucknow was as glorious as Kaiserbagh and none other was mutilated as badly. Today it requires great effort and imagination to recreate the vision of the palace complex as only a few structures of the Kaiserbagh palace remain. The important among these are Sufaid Baradari, some parts of Paree Khana, and the Lakhi gates. Sher Darwaza and the two tombs. The two tombs are protected monuments and well looked after by the Archeological Survey of India. The Baradari is used as a community hall and the Lakhi gates are in dilapidated condition whereas the Sher darwaza looks much diminished in size in most of it plinth has been silt. The Paree Khana has been modified beyond recognition. The presences of Lakhori bricks in these structures confirm their association with the palace complex. Two new buildings the Aminu-ud-daula library and Bhatkhande College of music are part of the main Kaiserbagh quadrangle. As the whole with the streets piercing in through the main quadrangular and heavy traffic plying through them, the essence of the garden palace is difficult to recreate.The riverfront swathe that was cleared. This included almost the entire kaiserbagh palace complex - what remains today is a part of the zenana, the "parikhAnA". A number of other buildings such as the Dilkusha and the Qadam Rasul were not allowed to be inhabited and gradually turned into ruins. [image: Veena Talwar: Making of the Colonial Lucknow, 1984, p.32]

Anindita Chakrabarti : The demolition of Lucknow

lec 38: Rural and Urban Sociology [ Objectives of the new urban planning: to create a rebellion-proof environment that would restore the confidence of the ruling class and make the capital a solid base from which the rest of the province could easily be governed and the revenue collected. Colonel Robert Napier of the Bengal Engineers, the Chief Engineer for reconstruction, proposed the following changes which aimed at improving the defense in the city: ● Establishing several military posts in prominent buildings of the city. ● Clearing the habitation and construction around these posts and along their lines of communication with the countryside. ● Opening broad streets through the city and practicable roads through and around the suburbs to ensure efficient and quick movement of troops to the danger spot. [AM: Interestingly the document does not speak of revenge - it only talks of security and safety, health etc. ] Large-scale demolitions were undertaken and Napier justified the destruction of two-fifths of the city by implying that the ‘dangerous overcrowding’ inside the old city would be automatically reduced with these demolitions.2 For the citizens of Lucknow this frenetic construction work where blasting was done with three days notice, was an extension of the battle they had just lost. ● The nawabi Machhi Bhawan fort which had commanding view of the two bridges and the densely built native city was converted to the principal post of the city. ● Clearing out a 600 yard wide esplanade in the most heavily populated and built up area of the city around Machhi Bhawan, for building roads that diverge through the city map. ● Napier justified the destruction of two–fifths of the city by implying that dangerous overcrowding inside the city would be automatically reduced with these demolitions. He professed that the losses incurred by individuals would be compensated by the benefits achieved for the community. ● Even the elementary precaution of ensuring that the buildings to be razed were empty was often not taken during demolition. The Asafi Imambara was taken over as regimental barracks. This was deeply resented as it was the tomb of their beloved nawab. British troops ate pork, swilled alcohol, trampled the sacred hall in regimental boots, and manifested every other kind of contempt for the religion of the old rulers of the province. ]

Contents

Foreword : Justice S.H.A Raza i

Prologue : Yogendra Narain, IAS iii

Preface : Roshan Taqui iv

Recommendations : 1st and 2nd International Conferences vii

1. Archaeological Sites and the Gazette of India

R. S. Fonia 1

2. First Census of Lucknow before first war of Independence

Roshan Taqui 10

3. Discovery of lost glory

Nayyar Masood 39

4. Dar-e-Daulat

M. Kaukab 44

5. The Queen Mother's visit to England

Rosie Llewellyn-Jones 59

The mother of Wajid Ali Shah goes to London to meet

the Queen - Wajid is supposed to go, but has been in

ill-health. While the group is in England, rebellion

breaks forth, possibly increasing the negative

reception. After a meeting with Queen Victoria and

her son Edward, the Queen-mother dies in Paris on the

way back and Wajid's brother dies a few months later.

They are both buried in Paris.

6. Period Photographs : The unpublished pages of Avadh history

P. C. Little 75

7. Impact of The West in the Court of Avadh

P.K. Ghosh 80

The Nawabs started learning western mores. A number

of scholars learned english and latin and started translating

texts into arabic and persian.

8. Avadh on the Eve of 1857 : Evidence of the Urdu newspaper "Tilism"

Iqbal Husain 89

Fascinating excerpts from the urdu weekly TIlism,

Lucknow. Tilism was brought out by Maulvi Muhammad

Yaqub Ansari (d.1903), of the every Friday from July 25

1856 till May 8 1857, right upto the eve of the

rebellion. It thus covered the period immediately after

the annexation of Oudh (Feb 1856) and the expulsion of

Wajid Ali Shah. The summaries provided by Hussain

documents a widespread disaffection with the English

rulers.

[The journal was written in ornate and elegant Urdu,

It is among the earliest papers outside Calcutta.]

Also mentioned in the discussion of the census above.

This journal has remained largely unknown to

historians of the mutiny; IH first wrote about it and

then rudranshu has also mentioned it. It was hard to

find, but Aligarh Muslim University has managed to

procure a nearly full set (except issue 37) from the

heirs of the original publishers.

What struck me in the Tilism stories is the arrogance of

the British as a ruling race. In one incident, the Deputy

Commissioner of Police for Daryabad

fatally wounded a brahman when the latter

attempted to save himself by showing a bamboo

stick to the former's dog. The matter was

enquired into by the Commissioner. The Dy

Commissioner, by way of punishment, was

transferreed to another place.

[10 Oct 1856, 10 Apr 1857]

[somehow, the image of the british as benevolent

rulers is so ingrained that it is difficult to imagine

that a colonial officer could have killed a man for

merely showing a stick. Even granting that Tislim may

be underplaying the offence - maybe the dog was hit -

even then it is surely excessive, and the standard of

justice is surely not deserving a civilized

government.

Also, interestingly, the Tilism reports openly that

following the forced exile of the monarch, there was a

planned insurrection involving as many as 12,000

potential combatants. However, the british spy

network got wind of the affair and it was

extinguished.

What surprises me is the temerity of the press. Of

course, the Press act (Act XVI) of 1857 ("the gagging

act") had not yet come into force, and the press was

only monitored for intelligence purposes. the Tilism

was thus able to report it freely.

Nonetheless, the very presence of such an act,

occurring outside the native soldiery, certainly gives

impetus to those theories of broader participation

among the citizenry, especially in Awadh.

9. Avadh on the Eve of Annexation

Roshan Taqui 101

10. Growth of Unani System of Medicine in Avadh

S. M. K. H. Hamadani 111

11. Administration of Avadh During the Period of Nawabs

S. N. Singh 130

12. Contribution of Nawabs to the Classical Music

Meena Kumari 133

13. Dulari: The Consort of King Naseer-ud-din Haider

P.K. Ghosh 137

14. Lucknow As I know it

Jafar Abdullah 142

15. This Lucknow and That

Ratan Mani Lai 148

16. Contribution of Courtesans in the Culture of Avadh

Dr. Manju Tripathi 151

17. Need for Preservation of Islamic Calligraphy of Nawabi Buildings

in Lucknow

S. Anwar Abbas 155

18. Monument to Hunger

Roshan Taqui 158

[history of bara imambara]

19. The First Queen and Third King of Avadh in Exile at Chunar

S. Anwar Abbas 162

20. Conservation of the Imambaras; Search for a

Neeta Das 167

Solution

21. Stratification of Peasants in Avadh (1722-1856)

Hamid Afaq Qureshi 173

22. Peasantry in Economic Distress During the Great Depression: The

United Provinces of Agra and Oudh (1900-1940)

S.P. Mishra 179

23. Avadh 1856-1916: A Social, Political and Economic 185

History

Bibliography 188

blurb

History of Avadh is not so old. Take the case of Lucknow, its rapid growth started from 1775 when Asif-ud-daula shifted his capital from Faizabad to Lucknow and continued till 1856, when Avadh annexed to the territories of East India company’s rule. During this short span of 80 years, rapid changes took place in the political arena but the basic doctrine of the rulers prevailed-the religious harmony and Integrated Culture. First International Conference has been organized by HARCA, a Non-Government Organization, on November, 15,16,1998 at Lucknow on the same subject. The papers presented by learned historians and paras recommended by justice haider Abbas Raza (now Lokayaukta Uttaranchal) and the social activists like Prof. Roop Rekha Verma Ex-vice Chancellor of Lucknow University, Dr. Ajay Shanker, Director General ASI, have been included in this book. thirty seven Papers were presented in the conference including five in Urdu Language. After discussion with the experts 23 papers were chosen including two in Urdu. These two Urdu Papers were then translated into English namely “Discovery of Lost glory” by Dr. Nayyer Masood and “Growth of Unani System of Medicine in Avadh” by Dr. Hamadani. HARCA-The Historical and Archaeological Research and conservation Agency has started a series of Seminars, and workshops for crating awareness in the public for real understanding of the culture and solution to the problems of conservation of heritage buildings. This Book is the first in this series. About the Author Rashan Taqui was born in 1958 at Lucknow. He has been published 40 research papers out of which 32 were exclusively on the History of Avadh. He helped three research scholars in completing their Ph. Ds. He wrote about cultural heritage of Avadh and the last Integrated Cultural of the world. His two books "Lucknow Ki Bhand Parampara" (The Traditions of clown of Lucknow) wer the only books on the subjects. His two books on contribution of rulers of Avadh to Indian music and dance, namely "Bani" and "Chanchal" have already been published . He has been associated with theatre and wrote fourteen plays including "Dada Jan Ne Kaha Tha", "Bezuban Biwi", "Do Gaz Zameen", Yeh Ho Raha Hai", HIs two drama Collection, "Ajaib Nagar" and "Dada jan Ne kaha Tha" have been in the market. He also directed several plays including "Desire Under the Elms", "She Stoops to Conquer", "Gidh", "Chanakya" Chacha Chhakkan Ki Wapsi", "Khalid Ki Khala", "Uljhan" and "tamrapatra". Like old Lucknowites he believes in religious harmony and National Integration. At present he is member secretary HARCA, Historical & Archaeological Research and conservation Agency, which is looking after Conservation and Restoration of Heritage Buildings at Lucknow.

links and other sources

from "The Walled palaces of Kaiserbagh" : Anil Mehrotra and Neeta Das

http://travelersindia.com/archive/v6n2/v6n2-walled_palaces.html After the first war of Independence in 1857, the British ordered the demolition of Kaiserbagh, as it was the stronghold of the Nawabs under the leadership of Begum Hazrat Mahal, who had assumed leadership after her husband, Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, who was exiled in 1856. Kaiserbagh was slowly demolished and had wide streets passing through its main courtyards. No other building complex of Lucknow was as splendid as Kaiserbagh and no other historical monument was so completely destroyed. Today it requires considerable imagination to recreate the vision of the palace complex as only a few structures of the Kaiserbagh palace remain. The impregnable complex of yesteryear today stands fragmented. The tombs, imposing in their solitude, have neatly laid out lawns where frolicking kids roll down their grassy embankments. The internationally famous Bhatkhande College of Music stands on the remnants of the palace structures, which, during the time of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, patron entertainer and music connoisseur, echoed with ghazals, thumris, and dadra. The Sufed Baradari, other than its royal occupants, stands unchanged in the midst of the complex. Graceful, with flowing contours in marble, it is witness to various events and thousands of marriages solemnized under its majestic marbled opulence. It continues to be one of the best-preserved edifices from the complex created by the Nawab. The two Lakhi gates are today but a shadow of their magnificent past. From dominating the entry into the palace complex, they appear humbled by the volume of traffic, rumbling under their aged portals. Aware of the cultural importance and heritage of the Kaiserbagh complex, the Government of Uttar Pradesh in close co-operation with the Archeological Survey of India has an ambitious plan to revitalize the area. [

Interview Roshan Taqui : 38,000 Indians were killed here

Apr 29, 2007 http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/sunday-toi/special-report/38000-Indians-were-killed-here/articleshow/1973989.cms?referral=PM Roshan Taqui's great grandfather and great granduncle were killed in Lucknow during the uprising. He is a government engineer by profession and has authored Lucknow 1857: The Two Wars at Lucknow . Another book on Begum Hazrat Mahal will hit the stands next month. Taqui is also secretary of the Historical & Archaeological Research Centre for Awadh (HARCA). What is your link to 1857? My grandfather Agha Mir Habeebi was posted with the Alambagh morcha (unit) at Jalalabad Fort, a few kilometres from Hazratganj. He was killed during the second relief of Lucknow, which I prefer to call the second war in 1858. He had 13 brothers, one of whom was Agha Najaf Ali, the jail doctor in Faizabad. Agha Najaf Ali befriended Maulvi Ahmadullah Shah, also known as the Faizabad Maulvi, who was one of the major figures of the uprising. Agha Najaf Ali helped the Maulvi to escape from Faizabad jail, allowing him to get to Lucknow, where he joined Begum Hazrat Mahal. Agha Najaf Ali was later hanged in 1858 at Khurshid Manzil, which is where the La Martiniere School for Girls is now located. There are some who feel the uprising started in Lucknow. I have written in my book that the war started on May 3 from Lucknow, and not on May 10 in Meerut as is commonly believed. On May 4, four people were hanged in front of the Rumi gate. They were sepoys who were no longer in service. How important was the coronation of Birjis Qadir? Without any leader, it was very difficult to fight the war against the British, and Birjis Qadir was the only legitimate son of the last king of Awadh. Hence his coronation was necessary. The administration of Qadir lasted for 8 months and 18 days. There has been plenty of character assasination of Begum Hazrat Mahal, but I believe she was a noble woman. How many Indians were killed in Lucknow during the uprising? I have drawn up a list of the people killed, from various sources, and would put the number of Indian casualties at 38,000. There are, however, many who believe that over a lakh died. How did the aftermath of 1857 impact Lucknow? The British took several repressive measures and citizens were not allowed to wear the traditional pagri (safa) and grow moustaches, the mark of soldiers in Awadh. They were also not allowed to move beyond Qaisarbagh towards Hazratganj, an area specified for Europeans only. The rich cultural heritage of Lucknow was totally destroyed. Has the uprising been adequately remembered? Nothing of note has been done. There is not even a plaque to mark the Battle of Chinhut near Ismailganj, slightly outside Lucknow, where Indian troops inflicted a heavy defeat on the British in 1857.

bookexcerptise is maintained by a small group of editors. get in touch with us! bookexcerptise [at] gmail [dot] .com. This review by Amit Mukerjee was last updated on : 2015 Apr 21