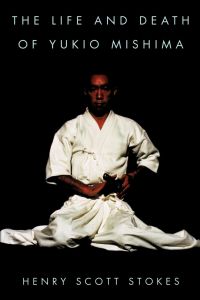

The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima

Henry Scott Stokes

Stokes, Henry Scott;

The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima

Rowman & Littlefield, 2000, 315 pages

ISBN 0815410743, 9780815410744

topics: | biography | lit | japan |

Stokes was a journalist covering Japan for the London TImes and later the New York Times, and spent two decades in Japan. He first met Mishima at a news conference, and got to know him well - he describes himself as a "friend".

Like many journalists, he is well-informed on local traditions, but his reading and his cultural affiliations are clearly to the west. Japanese culture comes to him through texts such as Ruth Benedict's _The Chrysanthemum and the Sword_, which is itself based on largely translated texts. (This book is mentioned twice as having received Mishima's praise.)

This stance is particularly bothersome when it comes to his literary analysis of Mishima's work. Thirst for Love is inspired by Mauriac. Influence of Dostoevsky, Camus, Mann, Blake is everywhere. In contrast, Japanese influences are not mentioned at all, though a number of Japanese authors are mentioned (e.g. as having taken their lives). The only such reference I could find is an affinity with Kobo Abe (born a year before Mishima).

Kobo Abé, described the vacuum of authority in a short note introducing his novel The Ruined Map: “In this city we have a huge, drifting vessel. Let us call it the ‘Labyrinth.’ Somewhere there must be a bridge, an engine room. But where? No one knows.” What Mishima and Abé had in common was a sense that Japan is adrift, out of control. p.281 In general, I find writing that is uninformed by original reading in the local language inferior, since it encodes what is essentially an outsider's perspective. To see the difference, one may contrast Donald Keene, and his perceptive analysis of Japanese literature, with the evident shallowness in Stokes. Of course it's true that Mishima (like modern authors everywhere) was influenced by western writing. This needs to be brought out. But he was also very well-exposed to traditional Japanese literature, and took his culture very seriously. These aspects are lost on the reader. Nonetheless, it is an interesting and racy read, and one of the more accessible texts on Mishima.

Excerpts

ch 1: The Last Day

[The first chapter opens with Mishima's celebrated suicide (seppuku). One is reminded of scenes from the 1985 movie by Paul Schrader, Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters.] Yukio Mishima rose early on the morning of November 25, 1970. He shaved slowly and carefully. This was to be his death face. There must be no unsightly blemishes. He took a shower, and put on a fresh, white cotton fundoshi, a loincloth. Then he dressed in his Tatenokai uniform. His wife, Yōko, had gone out with the children, taking them to school. He had the house—a large, Western-style home in the southwest suburbs of Tokyo—to himself. Mishima checked the items he was taking with him that day. He had a brown attaché case containing daggers, papers, and other things; he also had a long samurai sword and scabbard. On a table in the hall he placed a fat envelope. It contained the final installment of his long novel, The Sea of Fertility, on which he had spent six years. The envelope was addressed to his publishers, Shinchōsha... ... General Mashita was a dignified officer with gray hair. He was fifty-seven and had served through the Pacific War; he had a quiet, unpretentious manner. [The plan involves Mishima and four hand-picked Tatenokai students. One of them, Morita, will commit seppuku along with Mishima. The others are keen to do the same, but have been ordered to stay alive for recounting the tale for posterity. The detailed plan involves showing the general an ancient samurai sword, a rare piece. At this point, the general is expected to ask for a polishing cloth. A student will come up with the cloth, and now he will gag the general with it. But the general gets and gets the cloth himself. The student falls back. Later, at a cue from Mishima, they gag and tie up the general. The garrison gathers under the general's balcony. Mishima gives a speech, asking the army men to rise up for Nippon.]mishima giving his last speech from the balcony at the Ichigaya army base. He is in a Tatenokai uniform and is wearing a hachimaki (headband) with the rising sun.

Reactions to Mishima's speech : Seppuku

The crowd shouts -“Bakayarō!” [idiot, moron - baka=stupid, yarou=rascal] - “Who would rise with you?” - “Madman!” [Mishima returns to the general's office] Mishima started to undo the buttons of his jacket. He was in a part of the room, close to the door into the chief of staff’s office, from which he could not be seen through the broken window by the men in the corridor. The general watched as Mishima stripped off his jacket. Mishima was naked to the waist; he wore no undershirt. “Stop!” cried Mashita. “This serves no purpose.” “I was bound to do this,” Mishima replied. “You must not follow my example. You are not to take responsibility for this.” “Stop!” ordered Mashita. Mishima paid no heed. He unlaced his boots, throwing them to one side. Morita came forward and picked up the sword. “Stop!” Mishima slipped his wristwatch from his hand and passed it to a student. He knelt on the red carpet, six feet from Mashita’s chair. He loosened his trousers, slipping them down his legs. The white fundoshi (loincloth) underneath was visible. Mishima was almost naked. His small, powerful chest heaved. Morita took up a position behind him with the sword. Mishima took a yoroidōshi, a foot-long, straight-blade dagger with a sharp point, in his right hand. Ogawa came forward with a mōhitsu (brush) and a piece of paper. Mishima had planned to write a last message in his own blood. “No, I don’t need that,” Mishima said. He rubbed a spot on his lower left abdomen with his left hand. Then he pricked the knife in his right hand against the spot. Morita raised the sword high in the air, staring down at Mishima’s neck. The student’s forehead was beaded with perspiration. The end of the sword waggled, his hands shook. Mishima shouted a last salute to the Emperor. “Tennō Heika Banzai! Tennō Heika Banzai! Tennō Heika Banzai!” He hunched his shoulders and expelled the air from his chest. His back muscles bunched. Then he breathed in once more, deeply. “Haa . . . ow!” Mishima drove all the air from his body with a last, wild shout. He forced the dagger into his body with all his strength. Following the blow, his face went white and his right hand started to tremble. Mishima hunched his back, beginning to make a horizontal cut across his stomach. As he pulled at the knife, his body sought to drive the blade outward; the hand holding the dagger shook violently. He brought his left hand across, pressing down mightily on his right. The knife remained in the wound, and he continued cutting crosswise. Blood spurted from the cut and ran down his stomach into his lap, staining the fundoshi a bright red. With a final effort Mishima completed the crosscut, his head down, his neck exposed. Morita was ready to strike with the sword and cut off the head of his leader. “Do not leave me in agony too long,” Mishima had said to him. [Morita strikes Mishima with force. misses his neck twice and gives deep cut. Then...] Morita had little strength left in his hands. He lifted the glittering sword for the third time and struck with all his might at Mishima’s head and neck. The blow almost severed the neck. Mishima’s head cocked at an angle to his body; blood fountained from his neck. Furu-Koga came forward. He had experience in kendo, in Japanese fencing. “Give me the sword!” he said to Morita. With a single chop he separated body and head. The students knelt. “Pray for him,” Mashita said, leaning forward as best he could, to bow his head. A raw stench filled the room. Mishima’s entrails had spilled onto the carpet. Mashita lifted his head. The students had not finished. Morita was ripping off his jacket. Another student took from the hand of Mishima, which still twitched in a pool of blood, the yoroidōshi dagger with which he had disemboweled himself. He passed the weapon to Morita. Morita knelt, loosened his trousers, and shouted a final salute, as Mishima had done: “Tennō Heika Banzai! Tennō Heika Banzai! Tennō Heika Banzai!” Morita tried without success to drive the dagger into his stomach. He was not strong enough. He made a shallow scratch across his belly. Furu-Koga stood behind him, holding the sword high in the air. “Right!” said Morita. With a sweep of the sword Furu-Koga severed Morita’s head, which rolled across the carpet. Blood spurted rhythmically from the severed neck, where the body had slumped forward. [The three other students take the heads and place them, neck down, on the blood-soaked carpet. The headbands were still in place. p.9-32

Mishima bio

[from a journalist's party in Tokyo where Stokes first meets Mishima. ] He was born Kimitaké Hiraoka (Yukio Mishima was a pen name) in 1925, the eldest child of an upper-middle-class family living in Tokyo. His school record had been excellent and he had graduated top of his class at the exclusive Gakushūin (the Peers’ School) in 1944. At the age of nineteen he had traveled to the palace in central Tokyo to receive a prize, a silver watch, from Emperor Hirohito in person. (The following year, 1945, he had received a summons to an army medical, as a draftee, but he had failed that medical and had never served in the Japanese Imperial Army.) [in the movie, he is given to lie to the medical board as if he has tuberculosis. ] After the war, following graduation from the elite Tokyo University Law Department, he had taken the toughest job examination of all, the Ministry of Finance’s entrance examination, and passed with flying colors. Yet he had rejected a career in government—he would surely have pressed on to become a bank president or the like—and had opted to become a writer, a still more competitive choice of career. Seizing his opportunity, he completed a first major work, Confessions of a Mask, published in 1949, a book that touched on homosexual themes — and made him famous. At twenty-four he was hailed as a “genius” by Japanese critics. Thereafter, he published novels one after another at rapid speed. His outstanding works were The Sound of Waves (1954), a retelling of the romantic legend of Daphnis and Chloë in a Japanese setting, and The Temple of the Golden Pavilion (1956), a novel based on a celebrated arson incident in Kyoto—not long after war’s end, a monk set fire to one of Kyoto’s most famous old temples, burning it to the ground. Both works were translated and published in America in the 1950’s (though publication of Confessions of a Mask was delayed for a couple of years after its actual translation, to allow The Sound of Waves, a less controversial work, to come out first and to set Mishima’s reputation in the West as an uncommonly brilliant new writer). Mishima, said Roderick, was not only a novelist. He was a playwright, a sportsman, and a film actor. He had just completed a film of his short story Patriotism, a movie in which he played the part of the protagonist, a young army officer of the 1930’s who committed suicide with his wife—the officer by hara-kiri, his wife by cutting her throat. Mishima then stood up. He spoke, mainly, of his wartime experiences. He described the bombing of Tokyo in March 1945 and the appalling fires that swept the city, killing hundreds of thousands of Tokyoites on the worst night. “It was the most beautiful fireworks display I have ever seen,” he said in a jocular manner. Finally, he came to his peroration, concluding in his forceful if grammatically incorrect English, and spiking the ending with a surprising reference to his wife (“Yōko has no imagination”—spoken with a comic grimace)... It might be our . . . my basic subject and my basic romantic idea of literature. It is death memory . . . and the problem of illusion.

True beauty attacks and finally destroys

from 1971 article on the No theater published in This Is Japan: There [at the No] one may see in its original form a classical stage art that dates back to the fifteenth century, an art that, complete and perfect in itself, admits of no meddling by contemporary man . . . The No theater is a temple of beauty, the place above all wherein is realized the supreme union of religious solemnity and sensuous beauty. In no other theatrical tradition has such an exquisite refinement been achieved . . . True beauty is something that attacks, overpowers, robs, and finally destroys. It was because he knew this violent quality of beauty that Thomas Mann wrote Death in Venice . . . The No cannot begin until after the drama is ended and beauty lies in ruins. One might liken this . . . ‘necrophilous’ aesthetic of the No to that of works by Edgar Allan Poe, such as Ligeia or Berenice . . . In No lies the only type of beauty that has the power to wrest ‘my’ time away from the ‘exterior’ Japan of today . . . and to impose on it another regime . . . And beneath its mask that beauty must conceal death, for some day, just as surely, it will finally lead me away to destruction and to silence. p.388

Send your jottings to Book Excerptise

anyone can contribute their favourite extracts and scribblings to book excerptise.

to get started, just send us a first writeup with excerpts from your favourite book, headed by a short book review.

Format: plain text or wiki markup - please avoid MS word.

Email with the subject line "first writeup : name-of-book" to (bookexcerptise [at-symbol] gmail).

Your writeup will be circulated among the editors and should show up soon (under your name). If you find yourself contributing frequently, you may wish to join the editorial team.

bookexcerptise is maintained by a small group of editors. your comments are always welcome at bookexcerptise [at-symbol] gmail. This article last updated on : 2013 Oct 21