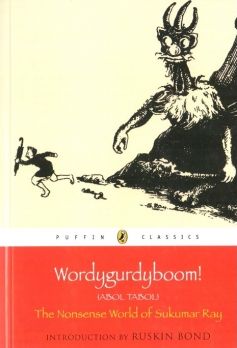

Sukumar Ray and Sampurna Chattarji (tr.)

Wordygurdyboom! (Abol Tabol আবোল তাবোল) : The Nonsense World Of Sukumar Ray

Ray, Sukumar; Sampurna Chattarji (tr.); Ruskin Bond (intro);

Wordygurdyboom! (Abol Tabol আবোল তাবোল) : The Nonsense World Of Sukumar Ray

Penguin India, 2004/2008, 173 pages

ISBN 0143330780, 9780143330783

topics: | poetry | nonsense | bengali | translation

sukumar rAy's nonsense verse is a staple of bengali childhood. rare is the bengali child who does not have a ready familiarity with almost the entire Abol tAbol - and this, i don't think can be said of any other children's author, perhaps in any language. to my view, this fact alone makes him one of the greatest children's writers in all literatures - though that is a hazardous remark to make.

his father was upendrakishor rAy, a pioneer children's writer and an accomplished artist who opened one of the early printing presses in bengal, and produced woodblocks. upendrakishor launched a children's magazine called sandesh in 1913 (the word is a sweetmeat popular with children, but can aso mean "news"). one of his stories, gupi gAin bAghA bAin (1915 sandesh), was made into a much-acclaimed film(1969) by sukumAr's son, the renowned film director satyajit rAy, who was also a popular author of detective and science fiction in bengali.

sukumAr rAy inherited sandesh after his father's untimely death in 1915, but he too fell ill in a few years. in fact, much of his nonsense verse was written while confined to the sick-bed. he died in 1923, when not quite 36, of a sandfly infection.

sukumar's wild imagination and his wicked verse have made him wildly popular, and much of his work even outside Abol tAbol (আবোল তাবোল) -- including the prose haw-jaw-baw-raw-law and the dAshu stories, both of which feature here, are intimately familiar to every bengali child, despite the gap of nearly a century. this volume also includes poems from khAi khAi, a collection of chhaRA focused on food themes (the title means "in the mood for food"). it also includes several prose pieces and five stories by rAy.

Superlative verse translations

translating poetry is not easy, and translating rhymed poetry while preserving the prosody and the rhyme is ridiculously difficult. the otherwise interesting work on indian nonsense poetry - Tenth Rasa by Michael Heynman (2007) includes a number of free verse translations of nonsense verse which simply do not work. in fact, that work is substantially redeemed by the copious selections from chattarji's work. here as well, she succeeds amazingly at this very challenging task.

Comparing with Sukanta Chaudhuri

there have been several english translations of Abol tAbol, most notably sukanta chaudhuri's the select nonsense of sukumar rAy (1987), which also is a very competent verse translation. while chattarji's renderings are in general, more lively, i still seem to prefer some of chaudhuri's versions for some poems. For example, with gAner gnuto গানের গুঁতো, I seem to prefer his version the power of music - to the otherwise competent rendering by chattarji (not in this volume), titled the song slam. similarly, i seem to prefer sukanta's super-beast to sampurna's wonster. on the whole though, while chaudhuri's verse is excellent english poetry, i feel that chatterji's renderings are perhaps more nimble and capture the wild humour of originals better. her translations not only preserve the nonsense elements, but for those familiar with the originals, they seem to be speaking almost in the same rhythm. here is an example: Come happy fool whimsical cool Come dreaming dancing fancy-free Come mad musician glad glusician beating your drum with glee [Glibberish-Gibberish, p.3] even if you don't speak bengali, perhaps you can get a flavour of what a difficult task this is - try reading out loud for both the above stanza and the original in latin script below (the "A" = aa): Ay re bholA kheyAl kholA svapandolA bAjiye Ay Ay re pAgal Abol tAbol matta mAdal bAjiye Ay আয়রে ভোলা খেয়াল-খোলা স্বপনদোলা নাচিয়ে আয়, আয়রে পাগল আবোল তাবোল মত্ত মাদল বাজিয়ে আয়। in the versions by chaudhuri, one finds somewhat rarer english words - here are how some commonplace bAnglA words are rendered: hnAs (হাঁস) : translated as "pochard" (sampurna has "duck") churi (চুরি, theft) : "purloined" (here: "stolen"), and TiyA (টিয়া) : "parakeet" - a more correct form than Sampurna's "parrot" these are perfectly fine choices, and were no doubt partly mandated by the rhyme structure, but they seem a bit more aloof and suppress the playful bounce of the originals. --- what more can I say? let's jump in the fray... Awesome songs!! Bring them on! Whimsic strong - 3 cheers for the bong!

Glibberish-Gibberish (Abol tAbol) p.3

Come happy fool whimsical cool

come dreaming dancing fancy-free,

Come mad musician glad glusician

beating your drum with glee.

Come o come where mad songs are sung

without any meaning or tune,

Come to the place where without a trace

your mind floats off like a loon.

Come scatterbrain up tidy lane

wake, shake and rattle and roll,

Come lawless creatures with wilful features

each unbound and clueless soul.

Nonsensical ways topsy-turvy gaze

stay delirious all the time,

Come you travellers to the world of babblers

and the beat of impossible rhyme.

Mish-Mash (khichuRi) p.5

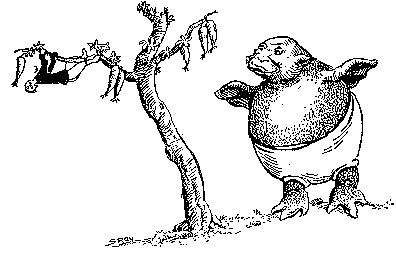

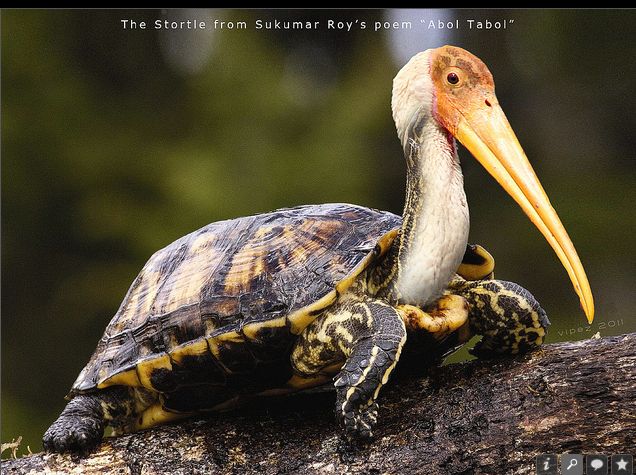

The stork told the tortoise, "Isn’t this fun! As the stortoise, we’re second to none!"A duck and a porcupine, no one knows how, (Contrary to grammar) are a duckupine now.

The parrot-faced lizard felt rather silly- Must he give up insects and start eating chilli? The goat charged the scorpion at a rapid run jumped on his back, now head and tail are one. The giraffe lost his taste for roaming far and wide, like a grasshopper he’d rather jump and glide.

The cow said. ‘Am I sick, too, from this disease? Or why should the rooster chase me, if you please?’ And oh the poor elewhale – that was a bungle, while whale yearns for the sea, ele wants the jungle. The hornbill was desperate as it had no horns, merged with a deer now, it no longer mourns.

Some other translations of this poem

Stew match (tr. Satyajit Ray)

A duck once met a porcupine ; they formed a corporation

Which called itself a Porcuduck ( a beastly conjugation ! ).

A stork to a turtle said, "Let's put my head upon your torso ;

We who are so pretty now, as Stortle would be more so !"

The lizard with the parrot's head thought : taking to the chilli

After years of eating worms -- is absolutely silly.

A prancing goat - one wonders why - was driven by a need

To bequeath its upper portion to a crawling centipede.

The giraffe with grasshopper's limbs reflected : Why should I

Go for walks in grassy fields, now that I can fly ?

The nice contented cow will doubtless get a frightful shock

On finding that its lower limbs belong to a fighting cock.

It's obvious the Whalephant is not a happy notion :

The head goes for the jungle, while the tail turns to the ocean,

The lion's lack of horns distressed him greatly, so

He teamed up with a deer - now watch his antlers grow !

---

Khichuri (tr. Prasenjit Gupta)

parabaas.com Was a duck, porcupine (to grammar I bow not) Became Duckupine, but how I know not. Stork tells turtle, “Indeed it’s a delight-- Our Stortle shape is exactly right!” Parrot-Head Lizard feels decidedly silly: Must he spurn all bugs for a raw green chili? The goat now hatches a plan to wed-- Mounts scorpion’s neck--body unites with head! The giraffe’s reluctant to wander nearby With his grasshopper wings, he longs to fly. Says the cow, “What disease has entered the pen That my rear belongs to a rascally hen?” Observe the Whalephant: whale wants the sea; Elephant says, “It’s the jungle for you and me.” The lion has no horns, that’s his woe-- He joins with a deer; and now antlers grow! ---

Hotch-Potch (tr. Sukanta Chaudhuri)

A pochard and a porcupine, defying the grammarians Combined to form a porcochard, unmindful of their variance A stork upon a tortoise grew, exclaiming "What a hoot!" A very handsome storkoise, now, we jointly constitute. A parakeet its features lent unto the lowly lizard, In puzzle whether flies or fruit would better suit its gizzard. The very goat began to feel impatient of its state : It leapt upon a scorpion's back, and grew incorporate. The tall giraffe refused to roam its ancestral savannah, But tried to don a locust's wings, and glide in a graceful manner. The cow was led to view itself, and staggered from the shock : Its noble form had been usurped by some designing cock. And rent by schizophrenia the whalephant we view : The open seas, the forest trees, are tearing it in two. The lion longed for antlers, and was doomed to dwell in care Until a stag suppplied it with a truly splendid pair.

original bAnglA

--খিচুড়ি-- হাঁস ছিল, সজারু, (ব্যাকরণ মানি না), হয়ে গেলে "হাঁসজারু" কেমনে তা জানি না। বক কহে কচ্ছপে "বাহবা কি ফুর্তি! অতি খাসা আমাদের বকচ্ছপ মূর্তি।" টিয়ামুখো গিরগিটি মনে ভারি শঙ্কা পোকা ছেড়ে শেষে কিগো খাবে কাঁচা লঙ্কা? ছাগলের পেটে ছিল না জানি কি ফন্দি, চাপিল বিছার ঘাড়ে, ধড়ে মুড়ো সন্ধি! জিরাফের সাধ নাই মাঠে ঘাটে ঘুরিতে, ফড়িঙের ঢং ধরি, সেও চায় উড়িতে। গরু বলে, "আমারেও ধরিলো কি ও রোগে? মোর পিছে লাগে কেন হতভাগা মোরগে?" হাতিমির দশা দেখ , তিমি ভাবে জলে যাই, হাতি বলে, "এই বেলা জঙ্গলে চল ভাই"। সিংহের শিং নেই, এই তার কষ্ট হরিণের সাথে মিলে শিং হল পষ্ট।

a fan's recreation of a bakachhap (বকচ্ছপ) also known as a stortoise, storkoise, or stortle...

4 Pumpkin-Grumpkin (Kumro PAtash)

(If) Pumpkin-Grumpkin dances- Don't for heaven's sake go where the stable horse prances Don't look left, don't look right, don't take no silly chances. Instead cling with all four legs to the holler-radish branches. (If) Pumpkin-Grumpkin runs- Make sure you scramble up the windows all at once; Mix rouge with hookah water and on your face smear tons; And don't dare look up at the sky, thinking you're great guns! (If) Pumpkin-Grumpkin calls- Clap legal hats on to your heads, float in basisn down the halls; Pound spinach into healing paste and smear your forehead walls; And with a red-hot pumice-stone rub your nose until it crawls. Those of you who find this foolish and dare to laugh it off, When Pumpkin-Grumpkin gets to know you won't want to scoff. Then you'll see which words of mine are full of truth, and how, Don't come running to me then, I'm telling you right now.

5 The Ol’ Crone’s Home p.15

Mouthful of puffed rice, smiling and chomping, In a ricket-rackety house, a clickety crone is stomping. Bedful of cobbywebs, headful of soot, Inky-Blinky bleary eyes, back bent like a root. Pins old the house up, glue sticks it down, She herself licks the thread that winds all around. Don’t dare lean too hard or bare boards may break. Don’t cough hick-hack, the brick-brack will shake. Plonk goes the streetcart, honk goes the car, Smash goes the beam, crash the house on to the tar. Wonky-wobbly are the rooms, holey-moley walls, Swept with dusty brooms causing musty splinter-falls. The ceiling gets soggy and saggy in the rain, The ol’crone all alone props a stick in vain. Fix it, nix it, day and night a-grouse, The clickety-clackety crone in her rickety-rackety house.

7 Wordygurdyboom (shabda-kalpa-droom) 21

Whack-thwack boom-bam, oh what a rackers Flowers blooming? I see! I thought they were crackers! Whoosh-swoosh ping-pong my ears clench with fear You mean that's just a pretty smell getting out of here? Hurry scurry clunk thunk - what's that dreadful sound? Can't you see - the dew is falling, you better stay housebound! Hush-shush listen! Slip-slop-sper-lash! Oh no the moon's sunk - glub glub glubbash! Rustle-bustle slip-slide the night just passed me by Smash-crash my dreams just shattered, who can tell me why? Rumble-tumble buzz-buzz I'm in such a tizzy! My mind's dancing round and round making me so dizzy! Cling-clang ding-dong my aches ring like bells - Ow-ow pop-pop oh my heart it burns and swells! Helter-skeler bang-bang 'help! help!' they're screeching- Itching for a fight they said! Quick! Run out of reaching! (tr. Sampurna Chatterjee) p.14

শব্দকল্পদ্রুম

ঠাস্ ঠাস্ দ্রুম দ্রাম,শুনে লাগে খটকা-- ফুল ফোটে? তাই বল! আমি ভাবি পট্কা! শাঁই শাঁই পন্ পন্, ভয়ে কান বন্ধ-- ওই বুঝি ছুটে যায় সে-ফুলের গন্ধ? হুড়মুড় ধুপধাপ--ওকি শুনি ভাইরে! দেখ্ছনা হিম পড়ে-- যেও নাকো বাইরে। চুপ চুপ ঐ শোন্! ঝুপ ঝাপ্ ঝপা-স! চাঁদ বুঝি ডুবে গেল? গব্ গব্ গবা-স! খ্যাঁশ্ খ্যাঁশ্ ঘ্যাঁচ্ ঘ্যাঁচ্ , রাত কাটে ঐরে! দুড়দাড় চুরমার--ঘুম ভাঙে কই রে! ঘর্ঘর ভন্ ভন্ ঘোরে কত চিন্তা! কত মন নাচ শোন্--ধেই ধেই ধিন্তা! ঠুংঠাং ঢংঢং, কত ব্যথা বাজেরে-- ফট্ ফট্ বুক ফাটে তাই মাঝে মাঝে রে! হৈ হৈ মার্ মার্ "বাপ্ বাপ্" চিৎকার-- মালকোঁচা মারে বুঝি? সরে পড়্ এইবার।

21 Stand-Alones Together

[shunechha ki bale gelo]

Did you hear what he said, the old fool?

The sky, it seems, smells sour as a rule!

But the sour smell vanishes when rain falls like sleet

And then - I've tasted it myself - it's absolutely sweet!

(tr. Sampurna Chatterjee) p.14

[how about "utterly" instead of "absolutely" there?]

শুনেছ কি বলে গেল সীতারাম বন্দ্যো

শুনেছ কি বলে গেল সীতানাথ বন্দ্যো? আকাশের গায়ে নাকি টকটক গন্ধ ? টকটক থাকে নাকো হ'লে পরে বৃষ্টি- তখন দেখেছি চেটে একেবারে মিষ্টি (correct source at bn.wikisource most sites on the web have the last line as "তখনও দেখেছি চেটে", which adds a third beat to the first word and completely spoils the prosody / rhythm. )

The Scent Predicament (gandha bichAr)

The king sat down on his throne to the crash of bell and gong. The old minister’s mind was seized by a tremor deep and strong. “What’s that smell about you,” said the king to his minister. “A scent, my king,” came the reply, “sweet more than sinister!” “Sweet or sour, let the doctor tell,” announced the king. Said the doctor, “With my stuffy nose I cannot smell a thing.” The king hollered, “Send then for Ram Narayan Scruff!” Said Scruff, “I cannot Sire, I’ve just taken some snuff. Stuffed with snuff no smell can enter, not a whiff.” Said the king, “Step forward, constable, and prepare to sniff.” “Alas,” said the constable, “for of camphor I am reeking, So strong a smell obscures the other one you’re seeking.” The king said, “Champion wrestler Bhim Singh is my man!” Bhim said, “I feel so faint I don’t know if I can. Last night I had a fever Sire, I do solemn swear.” Saying this, Bhim Singh simply keeled over right there. Catching his brother-in-law at last from the courtly lot, The king said, “Chondro, why don’t you give it a shot?” Chondro said, “Execute me if that’s what you’re getting at, But to kill me with a smell, what sort of whim is that?” The head clerk aged ninety was present at the court— “My death is near, why should I fear,” this very old man thought. “They’re talking rubbish, Sire,” said the ancient to his lord, “I’ll do it, if you give the word, and also a reward.” The king said, “I’ll give you a thousand rupees neat.” At this, the old gent rose excited to his feet. Sniffed the robe the minister wore — inhaled with all his might, As the court in wordless wonder watched, the old gent stayed upright. Throughout the land hurrahs rang out, bells danced and drums did jive, My, what vigour in the oldie’s veins to have sniffed and stayed alive!

The Song Slam

gAner gnuto গানের গুঁতো All summer long you hear the song of Bhishmalochan Sharma— A sound that barges like armed charges from Delhi on to Burma! He sings detached and soaring, roaring with all his soul, That dinning sound on spinning heads extracts an awful toll. Wounded gravely pitching down, twitching restlessly and how— Yelling, “That song is killing me, stop trilling it right now.” Lying helpless by the road are the reinless bull and steed; Bhishmalochan baying on, paying not the slightest heed. Tails a-quiver maddened shiver, the beasts are wilting speedily, In a fume and smother, “Blast and bother!” they cry out needily. Creatures of the sea are so quietly amazed down in the deep, Generations of trees are on their knees crashing in a heap. In the empty air the birds flare, somersaulting till they’re weary, All come out and pleading shout, “Stop the song now, dearie.” The skies quake the walls break at the fury of his song, Still gustily the merry singer very lustily sings on. Till a masterful mad goat in blasterful high gear, Unfurled his horns and hurled himself at the singer’s rear. And so in fact that one act the song’s fate decided, “Uh-oh” said Bhishmalochan and then utterly subsided.

Alternate transl. by Sukanta Chaudhuri : The Power of Music

When summer comes, we hear the hums

of Bhisma Lochan Sharma.

You catch his strain on hill and plain

from Delhi down to Burma

He sings as though he's staked his life, he sings

as though he's hell-bent;

The people, dazed, retire amazed

although they know it's well-meant.

They're trampled in the panic rout or languish

pale and sickly,

And plead,"My friend, we're near our end,oh

stop your singing quickly !"

The bullock-carts are overturned, and horses

line the roadside;

But Bhisma Lochan, unconcerned, goes

booming out his broadside.

The wretched brutes resent the blare the hour

they hear it sounded,

They whine and stare with feet in air or wonder

quite confounded.

The fishes dive below the lake in frantic search

for silence,

The very trees collapse and shake - you hear the

crash a mile hence -

And in the sky the feathered fly turn turtle while

they're winging,

Again we cry,"We're goingto die, oh won't you

stop your singing?"

But Bhisma's soared beyond our reach, howe'er

we plead and grumble;

The welkin weeps to hear his screech, and mighty

mansions tumble.

But now there comes a billy goat, a most

sagacious fellow,

He downs his horns and charges straight, with

bellow answ'ring bellow.

The strains of song are tossed and whirled by

blast of brutal violence,

And Bhisma Lochan grants the world the golden

gift of silence.

Introduction : Ruskin Bond

I : from ABOL TABOL

1. Glibberish-Gibberish 3 2. Mish-Mash 5 3. Wise Old Woody 9 4. Pumpkin-Grumpkin 12 5. The Ol' Crone's Home 15 6. Wonster 18 7. Wordygurdyboom! 21 8. Where do They Go on a Wild Goose Chase? 23 9. Making it Clear 27 10. Dopey-Opey Olli 30 11. Blow Hot Blow Cold 33 12. The Billy Hawk Calf 36 13. Limey Cow 39 14. Notebook 42 15. One-off Into Two 45 16. Fear Not 46 17. Tickling Tom 48 18. Uncle's Contraption 51 19. A One and a Two 54 20. Very Strange 55 21. Stand-alones Together 56

II : from KHAI-KHAI

1. Pre Amble 59 2. Ripe and Ready 60 3. Greedy Guts 62 4. The Green-Eyed Monster's Song 65 5. Huffy-Puffy 67 6. No Wonder He's a Donkey! 70 7. Why? 73

III : OTHER Poems

1. Nonsense Gone-Sense 77 2. Picture Book 79 3. Show-Off 83 4. For Better or for Verse 84

IV : HAW-JAW-BAW-RAW-LAW

1. Ha w-Jaw-Baw-Raw-Law (Or a Twiddle-Twaddle To-Do) 89

V : FROM PAGLA DASHU

1. Dashu the Dotty One 129

VI : from BOHURUPEE

1. A Story 139 2. Gorgondola 143

VIII : OTHER STORIES

1. Really 153 2. The Diary of Cautious Chuckleonymous 156 Translator's Note 171 Classic Plus 173 Note: The Tenth Rasa (ed. Michael Heynman) has some additional poems such as Mister Owl and Missus (pyanchA Ar pyanchAni), and this issue of links: http://www.flickriver.com/photos/vipez/sets/72157625996776004/ frivolous images such as this "stortle" (bakachhap):

PERSONAL OBSESSIONS: A POLYPHONIC PURSUIT I’d like to briefly examine some of the challenges of translating poetry via the work done by modern Indian poets pursuing personal obsessions — Ranjit Hoskote’s translation of the Kashmiri mystic Lal Děd, Mustansir Dalvi’s translation of Iqbal’s Shikwa & Jawaab-e-Shikwa, Mani Rao’s translation of the Bhagavad Gita, and my translation of Sukumar Ray. Ranjit began translating Lalla at the age of almost twenty-two—the book came out twenty years later—because “she provided a connection to an ancestral past, to a homeland and a language” he had lost. Mani was reading the Gita in Sanskrit for her own edification (saadhana), when certain doubts made her turn to existing translations, reading which she “felt disappointed, the original so lively, the translations so stiff!” “One thing led to another” and she ended up translating the Gita, a text she confesses she’d never imagined engaging in “an intimate and enduring conversation with”. Mustansir was drawn by the “rousing words of Iqbal’s poetry, especially when read aloud,” the way they hit you “at a gut level”. As for me, I plunged into translation simply to see if I could bring into English the bounce, the limberness, the wise-crackery, tomfoolery, profundity and endlessly-inventive wordplay of Sukumar Ray’s Abol Tabol which I had loved since childhood. Translators, when talking about translation, tend to resort to metaphor. A mosaic, a Persian rug seen from the back in which “the pattern is apparent but not much more” (Robert Bly), the same melody played by a different instrument…. I decided to resort to specifics. What, I asked these poet-translators, were some of the tricky issues they faced, what were the rules they imposed on themselves, what frustrations, intentions, satisfactions? I knew mine. When translating Sukumar Ray I wanted, above all, to conjure the effect the original poems have on the eardrum, the grey cells, the funny bone. The naming of characters, onomatopoeia and puns were matters I resolved by trusting instinct allied with an affinity for rhyme. I sought English counterparts that would have the same impact rather than the same meaning. If the Bengali wordplay depended on multiple meanings, I looked for an equally versatile English word. Ditto for uniquely Bengali idioms. I maintained the rhyme schemes because they came naturally, read seamlessly.

asymptotejournal.com M. Lynx Qualey, May 5, 2014 "The Bengali literary mafia would say: 'This is untranslatable.'" When Indian author Sampurna Chatterji was growing up, she lived between several languages. Her father taught English, while her mother taught Bengali. In Chatterji’s own schooling, the instructional language was English, but she also learned Hindi and Sanskrit. “All this creates a sort of strange cacophony in the head,” Chatterji said at a professional seminar at this year’s Abu Dhabi International Book Fair, held from April 30 to May 5. But this “cacophony” also creates wonderful opportunities for linguistic connections. As she developed as a writer, Chatterji decided not to write in Bengali. “The burden of being Bengali was too much for me,” she said. Her teenage rebellion was not to go off and smoke, but to write in English. So she published collections of poetry and novels in English. But she continued to have lines of Sukumar Ray’s Bengali poetry knocking about in her head. Ray wrote “this incredible nonsense poetry and prose,” Chatterji said. Ray’s poetry was deeply influenced by Lewis Carroll and “difficult to explain, but you can feel it in your bones.” Others had understood the importance of Ray’s poetry, and there was an English translation of Ray’s poetry that was “very accurate,” Chatterji said, but it utterly lacked the joy she remembered. She wanted to see if she could re-enact the joy she’d felt when listening to and reading the poems, so she thought: “Let me see if I can do it.” “It was a moment of great hubris, because I thought I could” translate the poetry, Chatterji said. Whereas “the Bengali literary mafia would say: ‘This is untranslatable.'” Ultimately, Chatterji decided that “it seemed to me an awful shame that any Indian child who did not know Bengali should be deprived of this plentitude.” In English, this collection of poems became Wordygurdyboom, and Chatterji said she really had to exhort her linguistic muscles, particularly in translating the Bangla sound words. “Because in Bangla, we have sound words for almost everything.” “I had to really push myself,” she said, also noting that Ray’s “rhyming is impeccable but it sounds like conversation. I had to work very hard.” Although a good chunk of Bengali literature “is traveling into English thanks to many people in the publishing world being Bengali,” Chatterji said, this is not true of many languages.

Funtastic nonsense http://www.tribuneindia.com/2004/20040404/spectrum/book8.htm Abol Tabol: The Nonsense World of Sukumar Ray translated from the Bengali by Sampurna Chattarji. Puffin Books. Pages 172. Rs 199. If a book could smile, Abol Tabol would crinkle its eyes, lift the corners of its mouth and give you a naughty grin. The slim volume is everything in the world that is happy and mischievous. The Nonsense World of Sukumar Ray lives up to its name in such an endearing manner that you enjoy every minute of your stay there. If translating verse is a tough translation assignment, translating nonsense verse must be tougher still. Sampurna Chattarji has, indeed, done a commendable job of translating Abol Tabol. Even so, non-Bengali readers cannot help wondering how much better the book must be in the original. Fortunately, Sukumar Ray has done some striking drawings of his out-of-the-world characters to go with each piece. These evocative renderings bring alive a never-never land that might otherwise have been lost on those unable to imagine bizarre characters in outrageous situations like the ones in Mish-Mash. Mish-Mash A duck and a porcupine, no one knows how, (Contrary to grammar) are a duckupine now.

The parrot-faced lizard felt rather silly — Must he give up insects and start eating chilli? --- or this poem on the wonster A strange-looking beast is the wild-eyed wonster, Nag-nag all day you’ll hear from the monster.

The most wonderful thing about Ray’s verse is its sound. Sample this from a poem aptly titled Wordygurdyboom!, or better still say it out loud: Whack-thwack boom-bam, oh what a rackers Flowers blooming? I see! I thought they were crackers! Whoosh-swoosh ping-pong my ears clench with fear You mean that’s a pretty smell getting out of here? Hurry-scurry clunk-thunk — what’s that dreadful sound? Can’t you see the dew falling, mustn’t move around! Critics call this use of sound onomatopoeia — but never mind unpronounceable literary terms, Ray would have probably wanted it known as jolly good fun. If each of his verses have a couple of fun-filled fantastic characters, the stories, especially Haw-Jaw-Baw-Raw-Law and The Diary of Cautious Chuckleonymous, have a whole assembly of them. Though shorn of the acoustic gymnastics that make the poems so remarkable, the stories are nonetheless unforgettable for their bewildering array of madcap characters in the unlikeliest of situations. Born in 1887, Sukumar Ray inherited the children’s magazine Sandesh, where his nonsense writings first appeared, from his father Upendrakishore Roychoudhury. He died in 1923, just nine days before Abol Tabol was published. Sampurna Chattarji’s impeccable translation of his works appears to be effortless and shows none of the jarring incongruities that so often mar translations. Her translation will, if anything, bring greater appreciation of Ray’s writings. If you thought that nonsense writing was the exclusive preserve of Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear or Ogden Nash, Abol Tabol would make you revise your opinion. Not only does Ray live up to his reputation as "a master of nonsense", but with the sheer inventiveness of his words and drawings, he beats the best of the English masters by a mile and more.

Sampurna Chattarji bio

(from drunkenboat.com) Sampurna Chattarji is a poet, fiction-writer, and translator. Her books include The Greatest Stories Ever Told, Abol Tabol: The Nonsense World of Sukumar Ray, and Mulla Nasruddin (all published by Penguin/India). Abol Tabol was reissued as a Puffin Classic in July 2008 under the title Wordygurdyboom! Her poetry has been widely featured in Indian and international journals and anthologies. Her debut poetry collection Sight May Strike You Blind was published by the Sahitya Akademi (India’s National Academy of Letters) in 2007, and reprinted in 2008. June 2009 sees the release of her first novel Rupture from HarperCollins.

- Sight May Strike You Blind by Sampurna Chattarji (2007)

Mysterious, though the smell of butter in my hair

and pepper on my tongue

seems familiar, like a witch's cat. ... - The Tenth Rasa: An anthology of Indian nonsense by Michael Heynman and Sumanyu Satpathy and Anushka Ravishankar and Sampurna Chattarji (2007)

Idli lost its fiddli

Dosa lost its crown

Wada lost its wiolin

And let the whole band down.

... - The Select Nonsense of Sukumar Ray by Sukanta Chaudhuri (1987)

When summer comes, we hear the hums

of Bhisma Lochan Sharma.

You catch his strain on hill and plain

from Delhi down to Burma ... - khAi khAi by sukumar rAy and debabrata ghoSh (ill.) (2007)

আমরা ভালো লক্ষ্মী সবাই তোমরা ভারি বিশ্রী,

তোমরা খাবে নিমের পাচন, আমরা খাব মিসরি | ... - The Oxford India illustrated Children's Tagore by Sukanta Chaudhuri (ed) (1991)

bookexcerptise is maintained by a small group of editors. get in touch with us! bookexcerptise [at] gmail [dot] .com. This review by Amit Mukerjee was last updated on : 2015 Aug 20