vidyAkara and Daniel Henry Holmes Ingalls (tr.)

Sanskrit poetry, from Vidyākara's "Treasury"

vidyAkara (Vidyākara); Daniel Henry Holmes Ingalls (tr.);

Sanskrit poetry, from Vidyākara's "Treasury"

Harvard University Press, 1968, 346 pages [gbook]

ISBN 0674788656, 9780674788657

topics: | poetry | sanskrit | india | ancient

This is a selection of the poetry that suits more modern tastes, culled from Ingall's earlier complete translation of the 11th c. sanskrit poetry anthology, vidyAkara's subhAShitaratnakoSha. it contains 836 of the verses - about half of the original - which had originally been compiled in the famed libraries in the Buddhist monasteries of North Bengal in the 12th c.vidyAkara (second half of 11th c. AD), was a poet-scholar, perhaps an abbot at the noted jagaddala vihAra, a large buddhist center of learning in varendra, a medieval region comprising the present districts of pAbna, maldA, rAjshahi, bogrA, dinAjpur, and rangpur. jagaddala vihAra was most likely located in a village jagdal, in district Naogaon (N. Bengal, presently the left ear of Bangladesh) where a preliminary excavations have revealed a buddhist monastery. This anthology appears to have been a lifelong passion of Vidyakara, who created a collection of the finest "modern" verse around, based on the libraries at jagaddala, as well as the five other mahAvihAras in the monastic system supported by the Palas. But with the fall of the Pala dynasty in the 12th c., and the destruction of the monasteries in the Islamic period -- most notably the destruction of nAlanda by bakhtiyAr khilji in 1193 -- the manuscripts, which were completed no later than 1130 AD, disappeared from Bengal for several centuries. Here is a view of the Jagaddal architectural site in Bangladesh today:[The tattered cover of my volume. After several years of looking for it, I managed to locate this copy at an US useed-book shop.]

[Note: Ingalls notes that jagaddala was a heap of stones and that the name is "still borne by a small village in Malda district in East Bengal". Current anthropological excavations however, suggest that the site may be near the village of Jagdal in Dhamoirhat Upazila, Naogaon district, Bangladesh. (banglapedia). ]site of excavations at jagaddala vihara near naogaon, bangladesh, where vidyAkara is likely to have lived and worked. source: (dailystar)

Rediscovery of original manuscripts

The modern re-discovery of the manuscript of _subhAShitaratnakoSha_ was the lifelong work of another sanskrit scholar, Prof. V. V. Gokhale. Around the time of independence, Gokhale came across some photographs of a palm-leaf manuscript that had been located by the iconoclastic marxian-buddhist scholar Rahul Sankrityayan, in the Ngor monastery in Tibet in 1934. In one of the blurred images, he could make out the name of bhartr^hari, whose poems were then being compiled by his friend D.D. Kosambi. After many years of failed efforts at getting a clearer copy of the manuscript, Gokhale managed to get himself posted to the diplomatic corps in Tibet, but even then he was not able to secure a usable copy of the manuscript. Eventually, he managed to get Jawaharlal Nehru interested in the matter, and photocopies could be procured after intervention at the very highest levels. This manuscript, with just over a thousand verses, is thought to be a possible original, maybe Vidyakara's own copy [p.31]. Eventually a second much larger edition, with 1,728 verses was located in the private library of the royal priest or rAjaguru of Nepal, Pundit Hemaraja. These two versions were studied by Gokhale and Kosambi, and identified as different editions. Based on references in the palm-leaf manuscript that may point to shelfmarks in a library, Kosambi has argued that Vidyakara is likely to have used the manuscripts in the vihAra library for compiling his anthology. The first edition is thought to have been prepared shortly before 1100 AD, and the second, more complete edition no later than 1130AD.

"Modernist" verse

The verses reflected "modernist" trends not noted in earlier sanskrit verse anthologies such as the Subhashitavali of Vallabhadeva (10th c.), which tend to focus more on classicist themes such as the myths, as well as on erotic themes, and on moral or ethical aspects. Vidyakara, while including a majority of poems in these themes, also includes a good number of verses reflecting contemporary life in the villages. These remark on the lives of the lower-caste women, on birds and animals, and on the village experience, some of which can apply just as well today. 1152 Her graceful arm, raised to pull strongly on the rope, reveals from that side her breast; her shell bracelets jingle, the shells so dancing as to break the string. With her plump thighs spread apart and buttocks swelling as she stoops her back, the pAmarI draws water from the well - SharaNa The compilation by Gokhale and Kosambi became known to Daniel Ingalls, then the editor of the Harvard Oriental Series, which eventually published the volume (no. 42 in its series) as the authoritative record. This translation by Ingalls draws on that version. The poetry itself is remarkable in the eclecticism of the compiler, and also in the insights it provides into Indian courtly life, and also the glimpses of rural life in the late pre-Muslim eastern India. Vidyakara carefully organized his verse into themes, organized in 50 sections, dealing with Buddha, Shiva, and other gods, the seasons, love and lovers, periods of the day, characterizations of village life (jAti), humorous epigrams and verbal puzzles, moral maxims about flatterers and good men and misers, panegyrics and praise to poets, etc.

The poets: A modernist selection

Of the 275 identified poets, only eleven seem to be earlier than the

seventh century AD.

Like all compilers of verse, Vidyakara was a man of his times, and he liked

the poets and poetic taste flourishing around him. Thus, his choice of

poets, while including many from classical times (bhartr.hari 25, kalidasa,

14] tend to include more contemporaries and near-contemporaries than other

selections. Here's Ingall's list (p. 33)

rAjashekhara (900AD) 101 stanzas

murAri (800-900) 56 stanzas

bhavabhUti (725) 47 stanzas

vallaNa (900-1100) 42

yogeshvara (700-800) 33

bhartr.hari (400) 25

vasukalpa (950) 25

manovinoda (900-1100) 23

bAna (600-650) 21

acala(siMha) (700-800?) 20

dharmakIrti (700) 19

vIryamitra (900-1100) 17

which reveals two interesting facts:

- most of VidyAkara's favourite authors were close to him in time;

- most of them, excepting the fist three in the list, were close to him

in place. Vallana, Yogeshvara, Vasukalpa, Manovinoda,

Abhinanda - all appear to be Bengalis or at least easterners,

around the time of the Pala dynasty. (Introduction, p.33)

Several Pala princes and buddhist monks are also included, including

Dharmapala, Rajyaapala, Buddhakaragupta, Khipaka, and Jnanashri. Many

poets are not to be found in other compilations, though there is a large

overlap (623 verses) with saduktikarnamrita, compiled by Shridharadasa in

1205 AD.

Excerpts

In speaking here of "poetry" I shall refer to what the Indians call kAvya. There is much verse that is not poetry in this sense. Much Sanskrit verse is didactic (ritual, philosophy, astronomy, medicine etc.). Much is narrative, and only a small portion of this narrative verse is kAvya. When it is the plot of the narrative that holds our interest and furnishes our delight rather than a mood or suggestion induced by poetic means, we are not dealing with kAvya. 278. The skies, growing gradually peaceful, flow like long rivers across heaven, with sandbanks formed of the white clouds and scattered flights of softly crying cranes; rivers which fill at night with "aterlily stars. [vishAkhadatta] 282. The wagon track, marked with juice from the crushed cane, carries a flag of saffron-colored dust; a flock of parrots settles on the barley ears already bowed with grain; a school of minnows swims along the ditch from paddy field to tank and on the river bank the good mud cools the herd boy from the sun. abhinanda 283. The branches marked with mud appear as if just rubbed with unguents after bathing; the banks with tufts of milkweed flying in the wind resemble flocks of sheep; the wagtails, flying swiftly to their new-found shoreline, give to the rivers the likeness of anointed eyes; the wild geese against the Krishna-colored sky are beautiful as sea-shells. 288. With trees appearing now the flood is past, and wagtails scattering on the shore; with jewelry of royal geese, these rivers give delight; within whose smiling water the minnows rush in fear of being swallowed by the nearby beaks of hunting sheldrake. Dimboka

section 25: Young Woman

401. Whatever the gods with so much effort

gained from the sea

may all be found

in the faces of fair women:

the flowers of paradise in their breath,

the moon in their cheeks,

nectar in their lips,

and poison in their sidelong glances.

[lakShmIdhara]

410. The lotus and the moon

each seek to imitate your face,

for it is Love's victorious weapon

and cynosure of every eye.

Hence comes their rivalry

and hence the cold-rayed moon

forbids the lotuses to blossom.

[dharmAkara]

The woman offended

637. The same side-stepping of her glance and unclear words,

the same shrugging me away when I embrace her body;

again the contradicting every word and stubborn shaking of her head:

my wife by anger has become a bride again.

[sambUka]

[husband seeks to pacify through praise?]

639. By rising to greet him from afar

she circumvents their sitting on one seat;

by the pretext of fixing betel

she prevents his quick embrace.

She makes no conversation with him;

instead, gives orders to the servants;

her skill is such that by politeness

she satisfies her wrath.

[sri harSha, amarushataka]

645. Long have I practised frowning;

I have trained my eyes to close and taught my smile restraint.

I have applied myself to silence

and strengthened all my wits to keep me obdurate.

Such angry preparations have I made,

but whether they succeed or not depends on fate.

[dharmakIrti]

[can she maintain her anger when face-to-face? ]

850

svAsaH kim, tvarita gatiH, pulakita kasmAt, prasAdyAgatA, veNI vbhrashyati, pAdayornipatanAt, kShAmA, kimityuktibhiH | svedArdra mukham, Atapena, galitA nIvI, gamAdAgamAd dUti mlAnasarorUhadyutimuShaH svouShThasya kiM vakhyAsi || "Why such breathing?" "From running fast." "The bristling cheek?" "From joy at having won him over." " Your braid is loose." "From falling at his feet." "And why so wan?" "From so much talking." "Your face is wet with sweat." "Because the sun is hot." "The knot has fallen loose upon your dress." "From coming and from going." "Oh messenger, what will you say about your lip, the color of a faded lotus?"

868

Moths begin their fatal flight into the slender flame; bees, made blind by perfume, wait in the closing bud; the dancing-girls are putting on their paint as one may guess from here by the jingling of their bracelets as they bend their graceful arms. - malayarAja p.265

872

The ogress night, her body black with darkness and teeth growing brighter with the appearance of the stars, puts forth her tongue, the twilight, in the sky to eat the sun's flesh, red with his fresh blood.

568

When he had taken off my clothes, unable to guard my bosom with my slender arms, I clung to his very chest for garment. But when his hand crept down below my hips, what was to save me, sinking in a sea of shame, if not the god of love, who teaches us to swoon? Vallana

573

The night was deep, the lamp shone forth with heavy flame, and that darling is an expert in the rite which passion prompts; but, my dear, he made love slowly, slowly and with limbs constrained, for the bed kept up a creaking like an enemy with gnashing teeth Anonymous

section 35. Characterizations

vidyAkara calls this section jAti. In Sanskrit, jAti has a connotation of the universal, of category hood; it refers to some of the features that define a category - the cow-hood of the cow. This is the sense in which these poems characterize the objects they describe.

1148

I rolled them in a cumin swamp and in a heap of pepper dust till they were spiced and hot enough to twist your tongue and mouth When they were basted well with oil, I didn't wait to wash or sit; I gobbled that mess of koyi fish as soon as they were fried. [koi is still a delicacy in Bengal; it is noted for being able to survive for considerable times outside water.]

1150

The hawk on high circles slowly many times until he holds himself exactly poised. Then, sighting with his downcast eye a joint of meat cooking in the canDAlA's yard he cages the extended breath of his moving wings closely for the sharp descent, and seizes the meat half cooked tight from the household pot.

1151

At dawn the fledglings of the reed-thrush raise their necks, their red mouths open, palates vibrating with thirst; they flutter from the ground, their bodies trembling with their ungrown wings. Pushing each other by the river bank, from the blade-troughs of the prickly cane they drink the falling dew.

1152

Her graceful arm, raised to pull strongly on the rope, reveals from that side her breast; her shell bracelets jingle, the shells so dancing as to break the string. With her plump thighs spread apart and buttocks swelling as she stoops her back, the pAmarI draws water from the well - SharaNa original sanskrit:[pAmara - low caste of field workers]

1155

The kingfisher darts up high and shakes his wings. Peering below, he takes quick aim.

Then, in a flash, straight into the water,

he dives and rises with a fish. - vAkpatirAja ["uses a pronounced bengalism buDDati for "he dives]

1157

The dairy boy milks the cow with fingers bent beneath his overlapping thumb. He holds the ground with the ball of his feet and strikes with his two elbows at the gnats that sting his sides. Sweet is the sound of the milk, my dear, as its stream squirts into the jar held in the vice of his lowered knees. [upAdhyAyadAmra]

1160

The girl shakes off the glittering drops that play upon the ends of her disheveled curls and crosses her interlocking arms to check the new luxuriance of her breasts. With silken skirt clinging to her well-formed thighs, bending slightly and casting a hasty glance toward the bank, she steps out of the water. [bhojya-deva]

1161

At night in the toddypalm groves the elephants, their earfronds motionless, listen to the downpour of the raining clouds with half-closed eyes and trunks that rest upon their tusk-tips [hastipAka]

1163

The cat has humped her back; mouth raised and tail curling, she keeps one eye in fear upon the inside of the house; her ears are motionless. The dog, his mouthfull of great teeth wide open to the back of his spittle-covered jaws, swells at the neck with held-in breath until he jumps her [yogesvara]

1164

The heron, hunting fish, sets his foot cautiously in the clear water of the stream, his eyes turning this way and that. Holding one foot up, from time to time he cocks his neck and glances hopefully at the trembling of a leaf. [yogesvara]

1166

The horse on rising stretches backward his hind legs, lengthening his body by the lowering of his spine; then curves his neck, head bending to his chest, and shakes his dust-filled mane. In his muzzle the nostrils quiver in search of grass. He whinnies softly as with his hoof he paws the earth. [bAna] [p.237]

1168

The calves first spread their legs and, lowering their necks with faces raised, nuzzle the cows; then, as with heads turned back their mothers lick their hindquarters, happily they take the teat and drink. [cakrapANi]

1170

The religious student carries a small and torn umbrella; his various possessions are tied about his waist; he has tucked bilva leaves in his topknot; his neck is drawn, his belly frightening from its sunkenness. Weary with too much walking, he somehow stills the pain of aching feet and goes at evening to the brahmin's house to chop his wood.

1171

With shaking combs escaping from quick-darting beaks, fiercely flying at one another, with throbbing necks and hackles rising in a circle; each wounded time and again by the thick-driving spur as the other leaps, the two cocks, with swift-footed cruel attack, fight to their heart's content. [vararuci?]

1173

They charm the heart, these villages of the upper lands, white from the saline earth that covers everything and redolent with frying chickpeas. From the depths of their cottages comes the deep rumble of a heavy handmill turning under the fair hands of a pAmara girl in the full bloom of youth.

1174

The puff of smoke from the forest fire, black as the shoulder of a young buffalo, curls slightly, spreads, is broken for a moment, falls; then gathers its power gracefully, and rising thick, it slowly lays upon the sky its transient ornaments.

1175

When villages are left by all but a few families wasting under undeserved disaster from a cruel district lord but still clinging to ancestral lands, villages without grass, where walls are crumbling and the mongoose wanders through the lanes; they yet show their deepest sadness in a garden filled with the cooing of gray doves.

1177

Jumping from the corner of the house, the frogs hop a few tiptoes forward and then proceed with slow, bent feet, working at something in their throat; until, leaping upon a piece of filth, with half-eyes blazing and with mouths wide open as a crocodile's, they gobble up the flies.

1178

How charming are the women's songs as they husk the winter rice; a music interspersed with sound of bracelets that knock together on round arms swinging the bright and smoothly rising pounder; and accompanied by the drone of hum, hum breaking from the sharply heaving breasts. [yogesvara]

1179

He opens wide his eyes; then squints and rubs them with his hand. He holds it far away, then brings it close. He moves out into the sunlight; then remembers he has left his eyesalve. Thus the man far gone in age keeps looking at the book. [varAha]

1181

On the field bank where the mud is shallow the sparrows with short hops and bobbing breasts hunt out the seeds now whitening into sprouts.

1182

Her bracelets jingle each time her graceful arm is raised and as her robe falls back, there peeps forth the line of nail-marks along her breast. Time and again with swinging necklace she raises the shining pounder held in her soft hands. How beautiful is the girl who husks the winter rice. [vAgura]

1183

With slow hops the sparrow circles gracefully about his hen,

tail up, wings lowered, body panting with desire.

His chirping ceases from his longing for his mate,

who crouches, calling softly in increasing eagerness,

until trembling and with suddenness he treads her. [sonnoka]

ALT:The cock sparrow, tail up and body panting with lust,

drops his two wings to his sides and circles

about his hen with slow and graceful hops

1185

The herons, standing by the backwaters of winter streams, present to travelers a charming sight. First they strike downward at their feet, then shake their heads, with eyes suffused with tears by the dancing motion of a fat fish-tail slipping down their gullet. [madhukaNTha]

1191

The wild tribesmen honor with many a victim the goddess durgA of the forest who dwells in rocks and caves, pouring the blood to the local Genius at the tree. Then, joined by their women at close of day, they alternate the gourd-lyre's merriment with rounds of their well-stored liquor drunk from bilva cups. [yogesvara]

1286

The talkative and frivolous prevail, never the good in the world’s opinion. Waves ride on the ocean’s top; pearls lie deep. Anonymous

1731

Those who scorn me in this world have doubtless special wisdom, so my writings are not made for them; But are rather with the thought that some day will be born, since time is endless and the world is wide, one whose nature is the same as mine. Bhavabhūti links: * http://dakshinapatha.wordpress.com/2012/09/13/vidyakara/

Review: Wendy O'Flaherty Doniger

Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland,

No. 1 (1971), pp. 78-84

A far more consistent and, I think, successful level of translation

[compared to van Buitenen's mr^cchakaTika] is

achieved by Daniel H. H. Ingalls in his Sanskrit poetry.

This being a collection of highly stylized verse, one might think that

the translator had less of an obligation to Clio than to Erato, that

accuracy of historical detail might more justifiably be sacrificed to

grace and mood. This is not, however, the case. The astonishingly wide

range of this poetry makes it a wonderful source book for information

about ancient Indian religion, animals, psychology, philosophy,

geography, and sociology, as well as the more obvious themes of love,

court life, and the seasons. This wealth of detail, enhanced by Professor

Ingalls's learned and perceptive introductory notes (though the vast

array of more technical notes has been omitted for this edition), makes

the book a kind of encyclopaedia of ancient Indian life, a function which

it retains in the English version due to the painstaking accuracy of the

translations. (This quality also makes it an ideal "crib" for students

of Sanskrit kAvya, the first truly reliable text that can be used

without the guidance of a teacher.)

Yet the material is first and foremost poetry of the very highest level,

the best in Indian poetry: miniatures which avoid the crudeness of the

great Sanskrit epics and the rococo heaviness of the long mahAkAvyas,

combining the delicacy of the haiku with the strength of

Goethe. Ingalls's translation is at once elegant and accurate, a pleasure

to read as English verse, unrhymed, and yet completely faith ful to the

letter, mood, and detail of the Sanskrit. Alone of all the English

translations of Sanskrit poetry, this book retains the Indian quality of

the thought.

The brilliance of Ingalls's work and the consistent advantage of his

method can best be appreciated by a comparison with Professor John

Broughs' excellent translation of a number of the same poems in his

anthology, Poems from the Sanskrit (Penguin, 1968). Brough is an

unfaultable Sanskritist and a good poet; yet frequently he is unable to

strike the elusive balance between beauty and faithfulness that Ingalls

maintains throughout his longer volume; perhaps because Brough attempts

more, he fails more. In his introduction, Brough points out some of the

problems arising not only from the Sanskrit but from the nature of the

"receiving language". English poetic forms are particularly ill-adapted

to accommodate Sanskrit conventions, and it is due to the nature of

German, as well as to the brilliance of the German poet Rueckert, that

Ruckert's translations from the Sanskrit have long been considered

peerless. Brough generally uses strict, rhymed verse forms and

consequently errs in accuracy more often than in grace; he himself admits

as much when he says that he hopes that the translation "while carrying

as much as possible of the sense-content of the original, will also

convey to the reader some atmosphere similar to that of the original

poem" (p. 23; the italics are mine).

Now, it is as impossible to convey atmosphere without conveying sense as it

is to build a brick wall without using bricks. To convey atmosphere, the

translator must convey meaning and something else. Brough pinpoints the

flaw in his method but uses it none the less: "Verse-translations are too

often tepid and diffuse. One of the main reasons for this is the remarkable

ease with which so many translators succumb to the temptation to add

padding... While it is usually possible to avoid padding, some degree of

reworking or paraphrasing is often inevitable" (pp. 26 and 28).

Thus, even if one considers rhyme a desideratum, much must be sacrificed for

it, more than is justifiable. But rhyme is no longer a necessity in poetry,

and indeed the particular metres and rhyme schemes which Brough chooses are

often a negative force, destroying mood rather than creating it. Thus, in

addition to causing an inevitable loss of detail and compactness, the rhyme

frequently obscures the delicate mood and almost always ruins the flowing,

Indian quality of the verse. Thus in Ingalls's verse #1319 (Brough # 199),

the mood of stark pathos is obliterated by the rhyme in Brough's version:

Ingalls: A poor man's body

would soon break,

did the ropes of daydreams

not bind it tight.

Brough: The cage of this poor frame would

surely burst apart

But for the cords of fancy fashioned by

my heart.

Here the rhyme transforms a delicate observation

of the human condition into a Valentine jingle.

A similar comparison may be made between Ingalls's

verse# 330 and Brough # 181:

Ingalls: Behold the skill

of the bowman, Love;

that leaving the body whole,

he breaks the heart within.

Brough: The god of love can scarce be matched

In skill in shooting with his arrow;

My body is not even scratched,

And yet he's pierced me to the marrow!

(Similarly Ingalls 697-Brough 169; Ingalls 480 Brough 223).

Brough's rhyme often succeeds in humorous verses where Ingalls's literal

translation is rather like a laborious explanation of a silly joke, and

falls flat; and often Brough hits upon a particularly felicitous and

non-distorting verse form. Thus Ingalls478-Brough44:

Ingalls: Knowing that "heart" is neuter,

I sent her mine;

but there it fell in love.

So Panini undid me.

Brough: The grammar-books all say that 'mind' is neuter,

And so I thought it safe to let my mind

Salute her.

But now it lingers in embraces tender:

For Panini made a mistake, I find,

In gender.

Brough's verses 226 and 227 (Ingalls 1148 and 1290) succeed for the same

reason: they are featherweight in Sanskrit and treated by Brough with

spirit, humour, and great elan.

Yet, another humorous verse (Ingalls 1680) is so padded by Brough as to lose

its point entirely. The literal translation would be:

"Now always use herb-pair to-assuage passion fever:

Young-girl-lower-lip-honey-drink and breast pressure-handful-use."

Ingalls remains literal, merely rearranging the words to fit a smooth

English line:

You may always use two medicines

to soothe the fire of love:

a sip of honey from a young girl's lip

and a pinch or two of her breast.

His one minor deviation from the Sanskrit ("pinch or two") adds only two

syllables and makes clear the pun on medical doses and erotic gestures,

while his matter-of-fact tone neatly preserves the dry, tongue-in-cheek

spirit of the Sanskrit. Brough (157), on the other hand, blunts the point

and smothers it:

When the fever is caused by her looks and her voice,

The treatment of choice

Is a thrice-daily sip

Of her honey-sweet lip.

To avoid further harm,

And to keep the heart warm,

This follow-up treatment is known to be best:

The soothing and gentle warm touch of her breast.

(Professional secret, though?

Careful to keep it so!)"

Amusing as this poem is, it bears little resemblance to the Sanskrit, which

is wittier to boot.

Rhyme is not the only problem, of course; often Ingalls succeeds better than

Brough even when Brough does not attempt to rhyme, as in these lines about

the moon (Ingalls 905-Brough 83):

Ingalls: The cat, thinking its rays are milk,

licks them from the dish; ...

Brough: A ray is caught in a bowl,

And the cat licks it, thinking that it's milk.

The first is simply better poetry.

On the other hand, Brough's rhymed verses sometimes manage to capture the

Sanskrit nuance better than Ingalls does. In Ingalls's 1163 (Brough 222),

the tension of the poem inheres in the manner in which the Sanskrit strings

out a series of complex adjectives, half in the nominative and half in the

accusative, and only reveals at the last minute that the former refer to a

dog and the latter to a cat. The Sanskrit might be translated literally:

Having-a-somewhat-made-into-a-hump-back [accusative],

having-a-raised-twisting-crooked-tip-tail in-fear,

having-a-within-house-entered-one-eye [and] un-trembling-ear-pair,

having-a-saliva-smeared-split-open-mouth

corners-expanding-teeth-face [nominative],

having-a-breath-suppressed-swelled-neck,

the-dog leaps-upon the-cat.

Ingalls retains the descriptions of the animals, and holds back the action

until the end, but he separates the dog and cat into neat halves, and the

adjectives become a bit cumbersome:

The cat has humped her back;

mouth raised and tail curling,

she keeps one eye in fear upon the inside of the house;

her ears are motionless.

The dog, his mouthful of great teeth wide open

to the back of his spittle-covered jaws,

swells at the neck with held-in breath

until he jumps her.

Brough pads somewhat, but he maintains the suspense better, and the rhyme

succeeds in giving body to the cluster of adjectives without distorting the

cluster of adjectives. This is a very fine translation:

See, the arched back, the tail erected, stiff,

Bent at the tip and twisting, and the ear

Flat to the head, and the eye quick with fear

Darting a single glance, debating if

The way to get inside the house is clear:

And on the other side, its gullet fat

With panting, growling, hoarse with its own breath,

With sneering lips that lift to show his teeth,

And slavering jaws, the dog attacks the cat.

Yet none of the extant translations, not even Ingalls's, are like the

Sanskrit original; at best, they are accurate and graceful. Brough points

this out when discussing the qualities of compactness and compounding that

distinguish Sanskrit verse. After giving a literal translation of the

dog-cat poem (which I have used in the first, second, and fifth lines of my

literal rendition), Brough remarks that English, unable to reproduce

compounds (as German can), must attempt to recreate

by quite different means ... rather than strain to imitate structural

features of the original which English cannot accommodate. The

artificial use in English of long compounds, for example, would usually

destroy more important poetical qualities of the original.

Now, granted that the literal rendition of the dog-cat poem is a highly

unorthodox form of English verse, the English language can certainly strain

to accommodate it; and indeed it is basically more straightforward and more

easily comprehensible than the widely accepted English verse of Ezra Pound,

E. E. Cummings, and others.

... both Brough and Ingalls use compound forms, some without hyphens, in

verse 257-218:

Ingalls: Now the great cloud-cat,

darting out his lightning tongue,

licks the creamy moonlight

from the saucepan of the sky.

Brough: Look at the cloud-cat,

lapping there on high

With lightning tongue

the moon-milk from the sky!

The compounds allow both translators to keep the verse compact; the rhyme

causes Brough to pad with "on high," and he misses the final element of the

fourfold metaphor -- the saucepan that is the sky -- but basically this is a

successful verse in both versions, largely because of the force of the

compounds.

The translator's right and, indeed, duty to deviate from normal

English conventions is demonstrated in verse 559-211, where the point lies

in the repetition of "in yain" (mudhA), which takes on different meanings

as the poem progresses. In keeping with the English tradition, Brough uses a

different paraphrase for this term each time, while Ingalls sticks closer to

the Sanskrit and makes the point as the Sanskrit makes it, producing a poem

both more beautiful and more faithful than the other:

When in the height of passion

the clothes had fallen from her hips,

the glowing gems upon her girdle

seemed to clothe her in an inner silk;

whereby in vain her lover cast his eager glance,

in vain the fair one showed embarrassment,

in vain he sought to draw away the veil

and she in vain prevented him."

The translator from Sanskrit to English should feel less bound by the

conventions of English verse forms, in order to reproduce more closely the

effect of the Sanskrit.

Ingalls: Now the great cloud-cat,

darting out his lightning tongue,

licks the creamy moonlight

from the saucepan of the sky.

Brough: Look at the cloud-cat,

lapping there on high

With lightning tongue

the moon-milk from the sky!

The compounds allow both translators to keep the verse compact; the rhyme

causes Brough to pad with "on high," and he misses the final element of the

fourfold metaphor -- the saucepan that is the sky -- but basically this is a

successful verse in both versions, largely because of the force of the

compounds.

The translator's right and, indeed, duty to deviate from normal

English conventions is demonstrated in verse 559-211, where the point lies

in the repetition of "in yain" (mudhA), which takes on different meanings

as the poem progresses. In keeping with the English tradition, Brough uses a

different paraphrase for this term each time, while Ingalls sticks closer to

the Sanskrit and makes the point as the Sanskrit makes it, producing a poem

both more beautiful and more faithful than the other:

When in the height of passion

the clothes had fallen from her hips,

the glowing gems upon her girdle

seemed to clothe her in an inner silk;

whereby in vain her lover cast his eager glance,

in vain the fair one showed embarrassment,

in vain he sought to draw away the veil

and she in vain prevented him."

The translator from Sanskrit to English should feel less bound by the

conventions of English verse forms, in order to reproduce more closely the

effect of the Sanskrit.

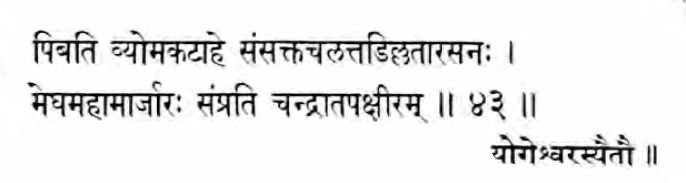

Review: Eloise Hart: Vidyakara: Cameos of Wisdom

http://www.theosophy.org.za/arts/ar-elo.htm Religious dedication did not prevent the 11th century Buddhist abbot Vidyakara from enjoying the sensuous realism and delicate artistry of the Sanskrit poetry he found in the library of his monastery at Jagaddala in East Bengal. When visiting neighboring scholars or entertaining traveling poets he invariably sought to exchange favorite verse and to discuss subtle meanings. Over the years he meticulously copied 1,738 of the best from earlier and contemporary poets into an anthology, "Treasury of Well-Turned Verse," of which two different copies have miraculously survived. ... When he read this Sanskrit text, Professor Ingalls was so charmed with its sophisticated style and poetic beauty that he immediately began translation into English, and after six years published Vidyakara's complete collection, together with a valuable introduction and interpretation, An Anthology of Sanskrit Court Poetry (Volume 44 of the Harvard Oriental Series, Harvard University Press). Its enthusiastic reception led him to select 836 of the most interesting and appealing verses in a smaller volume for general readers, Sanskrit Poetry (Harvard University Press). Sanskritists East and West were delighted to discover herein verses of over 200 poets whose work was believed to have been lost. Even in translation these stanzas retain their original lively spirit and give insight into Indian courtly attitudes and sensibilities of the pre-Muslim period. The poems he included on love and nature, the sketches of village life, the humorous epigrams and verbal puzzles, even the moral maxims and religious lyrics might have been written today -- the heartache, longings, joys and contentment of medieval India are common to all mankind. We might find in any country town 'strong peasant girls turning the rice mill,' 'fields of mustard turning brown,' a great 'bull pushing his way against the driving rain,' or an 'old woman shivering in her hut.' Nor does poetic fancy differ: 'The cloth of darkness inlaid with fireflies,' 'waves ride on the ocean top, pearls lie deep'; and 'The moon with bright mane flying in the forest of the night is like a lion . . .' was written by Panini long before William Blake penned 'Tyger, Tyger: burning bright in the forests of the night.' The restraint of the wife's joy when her long-absent husband returns, the realism of a faithful horse, and the pathos of a deserted tree will always touch the heart: Her husband has returned across the trackless desert; the mistress of the household looks upon his face with eyes unsteady from her tears of joy. She offers to his camel palm and thornleaf and from its mane wipes the heavy dust with the hem of her own garment, tenderly. -- Kesata (?) [512, p.148] The horse on rising stretches backward his hind legs, lengthening his body by the lowering of his spine; then curves his neck, head bending to his chest, and shakes his dust-filled mane. In his muzzle the nostrils quiver in search of grass. He whinnies softly as with his hoof he paws the earth. -- Bana [1166, p.237] The little birds have left, whom it had placed in honor on its head; the frightened deer are gone, whose weariness it once dispelled by granting of its shade. Alas, the monkeys too have run away, fickle creatures, once greedy for its fruit. The tree is left alone to bear the brunt of forest fire. -- Author unknown As a Buddhist, Vidyakara had little patience with the would-be ascetic too concerned with his own salvation to give thought to the suffering of others. He probably copied the following verse with a wry smile, then posed a question in the next from the Silhana collection: He has crossed all rivers of desire and contemned all pain. With grief at parting from his joys assuaged and impure thoughts removed, he has reached happiness at last and with closed eyes attains complete contentment. Who? Why, a fat old corpse in a graveyard. [anon. 1615, p.201] Can that be judgment where compassion plays no part, or that be the way if we help not others on it? Can that be law where we injure still our fellows, or that be sacred knowledge which leads us not to peace? [ShilhaNa collection 1629 p.303] Writing in the 'Perfected' Sanskrit language, the Indian poets distilled the vital essence of familiar experiences into miniature one-verse poetry so skillfully that it vibrantly reflected a timeless and universal quality. Its charm, like that of Chinese painting, is obtained by an illusive suggestiveness. One polished phrase, a single brush stroke, leads us from the mundane to heights of philosophical contemplation. How masterly Yogesvara, for instance, transports us with three or four words, from a cottage kitchen, where the family cat licks cream from a saucepan, to distant space where moonlight and lightning enchant our imaginations: Now the great cloud cat, darting out his lightning tongue, licks the creamy moonlight from the saucepan of the sky. पिबति व्योम-कटाहे सं सक्त-चलत्-तडिल्लता-रसनः | मेघ-महा-मार्जारस् सम्प्रति चन्द्रातप-क्षीरम् || Carl Sandburg wrote 'The fog comes on little cat feet,' and T. S. Eliot: 'The yellow fog that rubs its back upon the window-panes, . . . Licked its tongue into the corners of the evening, . . .' Yet neither launched the human spirit as successfully as does the short Sanskrit poem. The largest section of Vidyakara's "Well-Turned Verse" is devoted to love. Poems dealing with its every aspect, from the innocent coquetry of a young girl blooming into womanhood, the longing for an absent beloved, the excitement of love's intimacy and its joyous fulfillment, to the bodhisattva's selfless compassion, are delicately described, each with its own special beauty and woven together into the variegated tapestry of Indian life. The Western reader raising an eyebrow at the idea of monastic scholars enjoying -- even composing -- erotic verse fails to understand the Eastern mind which finds no incongruity with celibate purity. Which finds, indeed, love and religion synonymous. For while to them religion externalized man's inner aspirations and conflicts, love unites each human individual with the grand harmonies of universal life. The Hindu artist suggestively depicting a lofty pantheon of deities in voluptuous posture, and the Sanskrit poet describing physical and emotional pleasure, are both expressing metaphorically a mystical recognition of the oneness, interdependence and importance of life. To them personal suffering was the karmic reaction to voluntary disruption of cosmic harmony, and could be overcome only by its restoration through right and noble living. Thus Vidyakara's anthology encompassed the aspiring pilgrim who seeks to follow the way of the divine-human Buddha; who would tread the lonely path of self-conquest to enlightenment: No one rides before, no one comes behind and the path bears no fresh prints. How now, am I alone? Ah yes, I see: the path which the ancients opened up by now is overgrown and the other, that broad and easy road, I've surely left. -- Dharmakirti But for those who find the thirsts for life too strong, he quotes the Hitopadesa and, with a typically Indian-Buddhistic stoical indifference to pleasure and pain, advises them to seek stability in living a moral life: The body marches forward but the restless heart flies back like the silken cloth of a banner that is borne against the wind. -- Kalidasa Firmness in misfortune and in success restraint; skill in speech and bravery in battle; concern for honor and a love of holy writ . . . -- Hitopadesa These Sanskrit poems contain such intensity of feeling, such depths of meaning, one wishes to retain them all in some corner of the mind, to take them out from time to time and like rare cameos of wisdom savor their beauty in quiet reflection. (From Sunrise magazine, September 1970

review : Jan Gonda

Journal of the American Oriental Society, 87.1 (1967) It is a matter for regret that Professor Ingalls has not thrown overboard all incorrect or obsolete terminology. Terms such as " rhetoric " or " rhetorician " (pp. 372; 398)- instead of theorist (in the field of poetics and the art of composition)- can for instance create serious misunderstanding, because it is likely to suggest either the existence, in Ancient India, of professional orators or teachers of rhetoric of the Greek or Roman style, or the inferiority of the literary products under discussion. The repeated and likewise almost naturalized use of the English word pun for a particular stylistic procede of double-entente (e. g., p. 19; 373)-it is indeed hard to find another short term-should not make the reader believe that all instances of this device are humorous or-as the French jeu de mots-would suggest a play upon words in the sense commonly attached to the word play.-I am afraid that the remarks made (p. 6 f.) on the large choice of synonyms afforded by the enormous vocabulary of Sanskrit sound though they generally speaking are as far as they refer to the distinction between poetic words (such as vilasinf, mrgaks, yosit, etc., for "Cw oman ") and matter-of-fact words (shi-, nor-) -do not so often differ chiefly in sound and etymology only as seems to be Ingalls' opinion. This is not to say that any stanza contained in this collection will reveal its beauty, wit or delicacy of thought or feeling at once to all modern readers. [Gonda is an orientalist who never visited the east] ---blurb In this rich collection of Sanskrit verse, the late Daniel Ingalls provides English readers with a wide variety of poetry from the vast anthology of an eleventh-century Buddhist scholar. Although the style of poetry presented here originated in royal courts, Ingalls shows how it was adapted to all aspects of life, and came to address issues as diverse as love, sex, heroes, nature and peace. More than thirty years after its original publication, Sanskrit Poetry continues to be the main resource for all interseted in this multifaceted and elegant tradition.

bookexcerptise is maintained by a small group of editors. get in touch with us!

bookexcerptise [at] gmail [] com. This review by Amit Mukerjee was last updated on : 2015 Nov 25