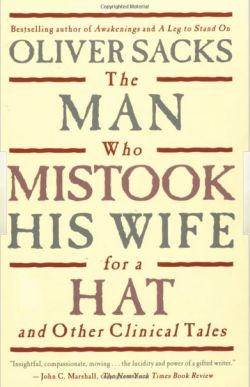

Oliver W. Sacks

The man who mistook his wife for a hat and other clinical tales

Sacks, Oliver W.;

The man who mistook his wife for a hat and other clinical tales

Simon & Schuster, 1987/1998, 243 pages

ISBN 0684853949, 9780684853949

topics: | psychology | case-study | perception | memory

When I got this copy in the 1980s from a book club in the US, it immediately enchanted me, and was perhaps one of the prime movers for my growing interest in Cognitive Science.

It records a fascinating series of cases observed by a neurologist in his rounds. The cases are counterintuitive, and provoke serious thoughts about the fragile interconnections that keep us going and maintain our sense of identity. Even the smallest slip and we may feel that one of our legs is not ours, or that someone we know intimately is a complete stranger.

Excerpts

4 The Man Who Fell out of Bed

[Sacks is called in to this case as a medical student. A new patient — a young man — seemed very nice, very normal... But after waking up from a snooze, he got very excited and somehow contrived to fall out of bed, and was now sitting on the floor, loudly refusing to go back to bed.]

When I arrived I found the patient lying on the floor by his bed and staring at one leg. His expression contained anger, alarm, bewilderment and amusement — bewilderment most of all, with a hint of consternation. I asked him if he would go back to bed, or if he needed help, but he seemed upset by these suggestions and shook his head. I squatted down beside him, and took the history on the floor. He had come in, that morning, for some tests, he said. He had no complaints, but the neurologists, feeling that he had a ‘lazy’ left leg — that was the very word they had used— thought he should come in. He had felt fine all day, and fallen asleep towards evening. When he woke up he felt fine too, until he moved in the bed. Then he found, as he put it, ‘someone’s leg’ in the bed — a severed human leg, a horrible thing! He was stunned, at first, with amazement and disgust — he had never experienced, never imagined, such an incredible thing. He felt the leg gingerly. It seemed perfectly formed, but ‘peculiar’ and cold. At this point he had a brainwave. He now realized what had happened: it was all a joke! A rather monstrous and improper, but a very original, joke! It was New Year’s Eve, and everyone was celebrating. Half the staff were drunk; quips and crackers were flying; a carnival scene. Obviously one of the nurses with a macabre sense of humor had stolen into the Dissecting Room and nabbed a leg, and then slipped it under his bedclothes as a joke while he was still fast asleep. He was much relieved at the explanation; but feeling that a joke was a joke, and that this one was a bit much, he threw the damn thing out of the bed. But — and at this point his conversational manner deserted him, and he suddenly trembled and became ashenpale— when he threw it out of bed, he somehow came after it — and now it was attached to him. ‘Look at it!’ he cried, with revulsion on his face. ‘Have you ever seen such a creepy, horrible thing? I thought a cadaver was just dead. But this is uncanny! And somehow — it’s ghastly — it seems stuck to me!’ He seized it with both hands, with extraordinary violence, and tried to tear it off his body, and, failing, punched it in an access of rage. ‘Easy!’ I said. ‘Be calm! Take it easy! I wouldn’t punch that leg like that.’ ‘And why not?’ he asked, irritably, belligerently. ‘Because it’s your leg,’ I answered. ‘Don’t you know your own leg?’ [...] But I want to ask you one final question. If this — this thing — is not your left leg’ (he had called it a ‘counterfeit’ at one point in our talk, and expressed his amazement that someone had gone to such lengths to ‘manufacture’ a ‘facsimile’) ‘then where is your own left leg?’ Once more he became pale — so pale that I thought he was going to faint. ‘I don’t know, he said. ‘I have no idea. It’s disappeared. It’s gone. It’s nowhere to be found ...

5 Hands

Madeleine J., 60 years old, is a congenitally blind woman with cerebral palsy, who had been looked after by her family at home throughout her life. She was in a pathetic condition — with spasticity and athetosis, i.e., involuntary movements of both hands... [But she was not retarded.] Quite the contrary: she spoke freely, indeed eloquently (her speech, mercifully, was scarcely affected by spasticity), revealing herself to be a high-spirited woman of exceptional intelligence and literacy. ‘You’ve read a tremendous amount,’ I said. ‘You must be really at home with Braille.’ ‘No, I’m not,’ she said. ‘All my reading has been done for me— by talking-books or other people. I can’t read Braille, not a single word. I can’t do anything with my hands — they are completely useless.’ She held them up, derisively. ‘Useless godforsaken lumps of dough — they don’t even feel part of me.’ I found this very startling. The hands are not usually affected by cerebral palsy — at least, not essentially affected... unlike the legs, which may be completely paralyzed... Miss J.’s hands were mildly spastic and athetotic, but her sensory capacities — as I now rapidly determined — were completely intact: she immediately and correctly identified light touch, pain, temperature, passive movement of the fingers. There was no impairment of elementary sensation, as such, but, in dramatic contrast, there was the profoundest impairment of perception. She could not recognize or identify anything whatever — I placed all sorts of objects in her hands, including one of my own hands. She could not identify — and she did not explore; there were no active ‘interrogatory’ movements of her hands — they were, indeed, as inactive, as inert, as useless, as ‘lumps of dough’. This is very strange, I said to myself. How can one make sense of all this? There is no gross sensory ‘deficit’. Her hands would seem to have the potential of being perfectly good hands — and yet they are not. Can it be that they are functionless—’useless’—because she had never used them? Had being ‘protected’, ‘looked after’, ‘babied’ since birth prevented her from the normal exploratory use of the hands which all infants learn in the first months of life? Had she been carried about, had everything done for her, in a manner that had prevented her from developing a normal pair of hands? And if this was the case — it seemed far-fetched, but was the only hypothesis I could think of— could she now, in her sixtieth year, acquire what she should have acquired in the first weeks and months of life? [...] I thought of the infant as it reached for the breast. ‘Leave Madeleine her food, as if by accident, slightly out of reach on occasion,’ I suggested to her nurses. ‘Don’t starve her, don’t tease her, but show less than your usual alacrity in feeding her.’ And one day it happened — what had never happened before: impatient, hungry, instead of waiting passively and patiently, she reached out an arm, groped, found a bagel, and took it to her mouth. This was the first use of her hands, her first manual act, in sixty years, and it marked her birth as a ‘motor individual’ (Sherrington’s term for the person who emerges through acts). It also marked her first manual perception, and thus her birth as a complete ‘perceptual individual’. Her first perception, her first recognition, was of a bagel, or ‘bagelhood’—as Helen Keller’s first recognition, first utterance, was of water (‘waterhood’). After this first act, this first perception, progress was extremely rapid. As she had reached out to explore or touch a bagel, so now, in her new hunger, she reached out to explore or touch the whole world. Eating led the way — the feeling, the exploring, of different foods, containers, implements, etc. ‘Recognition’ had somehow to be achieved by a curiously roundabout sort of inference or guesswork, for having been both blind and ‘handless’ since birth, she was lacking in the simplest internal images (whereas Helen Keller at least had tactile images). Had she not been of exceptional intelligence and literacy, with an imagination filled and sustained, so to speak, by the images of others, images conveyed by language, by the word, she might have remained almost as helpless as a baby. A bagel was recognized as round bread, with a hole in it; a fork as an elongated flat object with several sharp tines. But then this preliminary analysis gave way to an immediate intuition, and objects were instantly recognized as themselves, as immediately familiar in character and ‘physiognomy’, were immediately recognized as unique, as ‘old friends’. And this sort of recognition, not analytic, but synthetic and immediate, went with a vivid delight, and a sense that she was discovering a world full of enchantment, mystery and beauty.

Evolving into a sculptor

The commonest objects delighted her — delighted her and stimulated a desire to reproduce them. She asked for clay and started to make models: her first model, her first sculpture, was of a shoehorn, and even this was somehow imbued with a peculiar power and humor, with flowing, powerful, chunky curves reminiscent of an early Henry Moore. And then — and this was within a month of her first recognitions — her attention, her appreciation, moved from objects to people. There were limits, after all, to the interest and expressive possibilities of things, even when transfigured by a sort of innocent, ingenuous and often comical genius. Now she needed to explore the human face and figure, at rest and in motion. To be ‘felt’ by Madeleine was a remarkable experience. Her hands, only such a little while ago inert, doughy, now seemed charged with a preternatural animation and sensibility. One was not merely being recognized, being scrutinized, in a way more intense and searching than any visual scrutiny, but being ‘tasted’ and appreciated meditatively, imaginatively and aesthetically, by a born (a newborn) artist. They were, one felt, not just the hands of a blind woman exploring, but of a blind artist, a meditative and creative mind, just opened to the full sensuous and spiritual reality of the world. These explorations too pressed for representation and reproduction as an external reality. She started to model heads and figures, and within a year was locally famous as the Blind Sculptress of St. Benedict’s. Her sculptures tended to be half or three-quarters life size, with simple but recognizable features, and with a remarkably expressive energy. For me, for her, for all of us, this was a deeply moving, an amazing, almost a miraculous, experience. Who would have dreamed that basic powers of perception, normally acquired in the first months of life, but failing to be acquired at this time, could be acquired in one’s sixtieth year? What wonderful possibilities of late learning, and learning for the handicapped, this opened up. And who could have dreamed that in this blind, palsied woman, hidden away, inactivated, over-protected all her life, there lay the germ of an astonishing artistic sensibility (unsuspected by her, as by others) that would germinate and blossom into a rare and beautiful reality, after remaining dormant, blighted, for sixty years?

Postscript

The case of Madeleine J., however, as I was to find, was by no means unique. Within a year I had encountered another patient (Simon K.) who also had cerebral palsy combined with profound impairment of vision. While Mr K. had normal strength and sensation in his hands, he scarcely ever used them — and was extraordinarily inept at handling, exploring, or recognizing anything. Now we had been alerted by Madeleine J., we wondered whether he too might not have a similar ‘developmental agnosia’—and, as such, be ‘treatable’ in the same way. And, indeed, we soon found that what had been achieved with Madeleine could be achieved with Simon as well. Within a year he had become very ‘handy’ in all ways, and particularly enjoyed simple carpentry, shaping plywood and wooden blocks, and assembling them into simple wooden toys. He had no impulse to sculpt, to make reproductions — he was not a natural artist like Madeleine. But still, after a half-century spent virtually without hands, he enjoyed their use in all sorts of ways. This is the more remarkable, perhaps, because he is mildly retarded, an amiable simpleton, in contrast to the passionate and highly gifted Madeleine J. It might be said that she is extraordinary, a Helen Keller, a woman in a million — but nothing like this could possibly be said of simple Simon. And yet the essential achievement — the achievement of hands — proved wholly as possible for him as for her. It seems clear that intelligence, as such, plays no part in the matter — that the sole and essential thing is use.

bookexcerptise is maintained by a small group of editors. get in touch with us!

bookexcerptise [at] gmail [] com. This review by Amit Mukerjee was last updated on : 2015 Nov 26