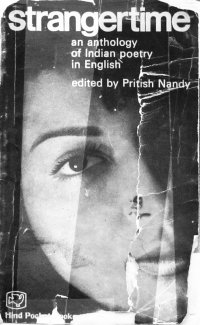

strangertime: an anthology of Indian Poetry in English

Pritish Nandy (ed)

Nandy, Pritish (ed);

strangertime: an anthology of Indian Poetry in English

Hind Pocket books 1977 218 pages

ISBN 0000

topics: | poetry | anthology | india | english

Book Review

as you can see from this rather tattered cover, this book came to me well-used, and since then it has seen a lot of page-turns. this book was completely unknown to me until a college street bookseller thrust a battered copy at me and the raw energy of the poems immediately captivated me. i think i paid rs. 10 or 20 for it, which is among my best buys for any book ever. here is real indian english poetry, poetry that breathes the raw spirit of living here, being indian.

growing up in a calcutta suburb in the seventies, when desmond doig was mesmerizing us budding anglophiles with the junior statesman, and all of us were lined up to be benji league members, pritish nandy was a name we knew but we hadn't read any of his thirty odd volumes of poetry - most of these have reached oblivion (well-deserved?). but this anthology, brought together in those heady times, breathes fire, and it is well worth the time for any lover of poetry.

published by hind books, it was meant to be a cheap edition objective being to get it into the hands of the indian poetry-lover, who was of course, forever cash-strapped. without an audience poetry is nothing, so the objective was to create an audience for this new fledgeling art. by the time it found me, around 2006, the paper was yellow and crumbling, the binding had fallen apart, and the haunting black and white cover image faded. the typeset is from a poor man's foundry, and there are many typos, some of which i have tried to fix a bit in my excerpts below (my edits are annotated in square brackets).

clearly, this was a labour of love. it is inspired by an amazing passion. the poets all speak to you, you feel it in the introduction, and while some of the poets i don't care for as much, the "where-the-page-falls-open quotient" is very high - i.e. - any chance encounter is likely to be well rewarded. the book also has considerable historical value. voices like agha shahid ali are being anthologized for the first time. arun kolatkar's jejuri has just come out, as has adil jussawala's missing persons. all the major voices of today are here, except for arvind mehrotra (at the time, he was away at the writer's workshop, iowa). for a description of the poetic energy of the times, you may want to read this piece by amitabha mitra. on the whole, one of my top books of indian english poetry, second only to mehrotra's twelve modern indian poets.

Contents

Introduction by Pritish Nandy A. K. Ramanujan Prayers to Lord Murugan (5 pages) Obituary Love poem for a wife Small-scale reflections on a great house The last of the princes Still another for mother Adil Jussawalla (bio at poetryinternationalweb) From 'Missing person' Agha Shahid Ali Shaving Storm K.L. Saigal Learning Urdu Taxidermist Note: all five poems are from his first book, Bone Sculptures, 1974 quite out of the publishers' radar today. Pls let me know if anyone who has a copy and would like to share (either a photocopy or a few of the lesser known poems). It is quite a lost book; it doees not figure in his so-called collected work: Veiled Suite: the collected poems. If you have a copy that you would like me to share excerpts from (or even if you would rather I didn't), pls let me know!! Arun Kolatkar The bus The Priest Heart of Rain The door A low temple The horseshoe shrine Bibhu Prasad Padhi Rains in Cuttack For Pablo Neruda From The Extra Medical Ward Letters Deba Patnaik Death is not dying Babna Baya My father's chair The clapping of one hand A toy is no toy if it does not break Against all silences to come Dilip Chitre Poem in self exile The nightmare is a peninsula Untitled Praxis Duties of a citizen Tukaram in heaven, Chitre in hell Gieve Patel (bio at poetryinternationalweb) Nargol The arrogant meditation Soot crowns the stubble Bodyfears, Here I stand University On killing a tree Imtiaz Dharker (homepage) Going home Jayanta Mahapatra Nowhere Coming of winter Song of the river Grass The beggar takes it as solace The Indian way Kamala Das Ghanashyam A man is a season A wound on my side Madness is a country Forest-fire My son's teacher The descendants Keki N Daruwalla The apothecary-I The professor condoles Advice to weak stomachs 109 Kohoutek Bombay prayers Mehar Ali - the keeper of the dead 114 Kersy Katrak (obit) The Radharani of the Hevajra Tantra For Adil and Veronique Dadyseth [man dying of cancer] Keshav Malik (wiki) The kingdom of despair Queen of hearts Importance Vishwarup M. F. Husain Poems Mrinalini Sarabhai Ananda Worship Nissim Ezekiel Chronic Minority poem A small summit Happening After reading a prediction The hill Prayag Bandopadhyay Shadows in the subway Pria Karunakar Iktara: Songs of the mendicant poet Pritish Nandy The nowhere man Rakshat Puri This and that 163 Rain 164 Seeker The painter Shah Ibrahim Seasonal round Randhir Khare A hymn in darkness Scream On the balcony Whispering firs Ruskin Bond Lone fox dancing Your eyes, glad and wondering Cherry tree Boy in a cemetery Not death Shiv K. Kumar A mango vendor To a prostitute My mother's death anniversary Broken columns Returning home Shree Devi In the eye of the sun 187 [Darjeeling setting] A village fair 189 Homecoming 191 [Meets old lover after her bad car accident] Yet I return 192 [lover is in too much of a hurry] Ultimately this 193 [lover is philandering] Siddhartha Kak The Indo-Anglian Antara [mixes in a hindi poem] Victims [woman revenges father, by ?making love?] Unawares [storm, is like love, unexpected] Subhas Saha The seven stages of love Subhoranjan Dasgupta Lost cities She who forgets Mausoleum Debt-return A defeatist's slogan for Lenin Suresh Kohli After the war Perturbed emotions Calcutta: Earth explodes S. Santhi Encores Something of you My name is another

Excerpts

Some pieces were available on the web, but I have typed in much of this hard to find text, my excitement in which I would love to share. Biographies are summarised from the back of the book; phrases like "just published", "currently" etc refer to the mid-70s.

From the introduction (by Pritish Nandy)

I have attempted this somewhat heretic, breakaway selection. Personally, I would have preferred to make an even more audacious break with the existing formula. But objectivity is the bane of most anthologists. Hence most of the familiar names are here as well. But you will also find young, experimental poets, who have not appeared in such anthologies before. Good poets. Daring poets. Poets who have taken the occasional risk with the printed word. You will find here a few familiar names from other disciplines. The celebrated dancer Mrinalini Sarabhai is represented by two remarkable poems, M.F. Husain... Ruskin Bond has in his simple, unpretentious style, fashioned some fascinating lyrics, quite different from the grim landscape of contemporary Indo-English poetry. There is Arun Kolatkar, the artist and visualizer, represented by selections from his brilliant first book, Jejuri. And of course, Gieve Patel, one of our finest contemporary painters. not so familiar names: Deba Patnaik, Jayant Mahapatra, and S. Santhi, all of whom have been widely published and recognised overseas. Also new names like Agha Shahid Ali, Pria Karunakar, Siddhartha Kak, Imtiaz Dharker, Randhir Khare, Subhas Saha, Bibhu Prasad Padhi and Shree Devi, who have been published in many magazines but have not been anthologized before. Things have changed [in the last decade]. Indo-English poetry, whatever may be its rating compared to language writing, seems firmly entrenched in the Indian literary scene today. Despite the sahibs who still harbour hopes of making it big overseas. Some do, true. Dom Moraes has made it, after his fashion. But for most of us the priorities are quite different. And some of us have made it where we always wanted to: right here, where the action and the living audience is. The anthology is therefore not defensive. It celebrates our success. It attempts to capture the drama, the intensity, and the sheer vitality of the poetry being written today. It is a statement of faith as well. Faith in the future of such writing. The poems in this book span roughly the last decade: a period in which, I believe, Indo-English poetry has found itself. There is less self-consciousness, less of an attempt to hitch our wagon to the lodestar of British poetry. There is a greater awareness that Indian writing in English must relate to the Indian literary scene. Our roots lie here; this is our literature. So it must reflect our concerns, discover our root metaphors - rather than seek salvation under another sky, [another milieu] that inspired our predecessors to write pathetic elegies to springtime beside the Thames in the hope of finding readers and promoters in distant climes. The poets I present here have chosen their own poems. I have only tried to put this informal selection into shape. Calcutta 1977 Pritish Nandy

A.K. Ramanujan

(b. Mysore 1929. Deccan College, Poona -> Indiana U on Fullbright. Prof Dravidian studies and Linguistics at U. Chicago. ]

PRAYERS TO LORD MURUGAN : A.K. Ramanujan : p.17

1 Lord of new arrivals lovers and rivals: arrive at once with cockfight and banner— dance till on this and the next three hills women's hands and the garlands on the chests of men will turn like chariotwheels O where are the cockscombs and where the beaks glinting with new knives at crossroads when will orange banners burn among blue trumpet flowers and the shade of trees waiting for lightnings? 2 Twelve etched arrowheads for eyes and six unforeseen faces, and you were not embarrassed. Unlike other gods you find work for every face, and made eyes at only one woman. And your arms are like faces with proper names. 3 Lord of green growing things, give us a hand in our fight with the fruit fly. Tell us, will the red flower ever come to the branches of the blueprint city? 4 Lord of great changes and small cells: exchange our painted grey pottery for iron copper the leap of stone horses our yellow grass and lily seed for rams! flesh and scarlet rice for the carnivals on rivers O dawn of nightmare virgins bring us your white-haired witches who wear three colours even in sleep. 5 Lord of the spoor of the tigress, outside our town hyenas and civet cats live on the kills of leopards and tigers too weak to finish what's begun. Rajahs stand in photographs over ninefoot silken tigresses that sycophants have shot. Sleeping under country fans hearts are worm cans turning over continually for the great shadows of fish in the open waters. We eat legends and leavings, remember the ivory, the apes, the peacocks we sent in the Bible to Solomon, the medicines for smallpox, the similes for muslin: wavering snakeskins, a cloud of steam Ever-rehearsing astronauts, we purify and return our urine to the circling body and burn our faeces for fuel to reach the moon through the sky behind the navel. 6 Master of red bloodstains, our blood is brown; our collars white. Other lives and sixty- four rumoured arts tingle, pins and needles at amputees' fingertips in phantom muscle 7 Lord of the twelve right hands why are we your mirror men with the two left hands capable only of casting reflections? Lord of faces, find us the face we lost early this morning. 8 Lord of headlines, help us read the small print. Lord of the sixth sense, give us back our five senses. Lord of solutions, teach us to dissolve and not to drown. 9 Deliver us O presence from proxies and absences from sanskrit and the mythologies of night and the several roundtable mornings of London and return the future to what it was. 10 Lord, return us. Brings us back to a litter of six new pigs in a slum and a sudden quarter of harvest Lord of the last-born give us birth. 11 Lord of lost travellers, find us. Hunt us down. Lord of answers, cure us at once of prayers.

OBITUARY : A.K. Ramanujan : p.22

Father, when he passed on, left dust on a table of papers, left debts and daughters, a bedwetting grandson named by the toss of a coin after him, a house that leaned slowly through our growing years on a bent coconut tree in the yard. Being the burning type, he burned properly at the cremation as before, easily and at both ends, left his eye coins in the ashes that didn't look one bit different, several spinal discs, rough, some burned to coal, for sons to pick gingerly and throw as the priest said, facing east where three rivers met near the railway station; no longstanding headstone with his full name and two dates to hold in their parentheses everything he didn't quite manage to do himself, like his caesarian birth in a brahmin ghetto and his death by heart- failure in the fruit market. But someone told me he got two lines in an inside column of a Madras newspaper sold by the kilo exactly four weeks later to streethawkers who sell it in turn to the small groceries where I buy salt, coriander, and jaggery in newspaper cones that I usually read for fun, and lately in the hope of finding these obituary lines. And he left us a changed mother and more than one annual ritual.

SMALL-SCALE REFLECTIONS ON A GREAT HOUSE : A. K. Ramanujan : p.27

Sometimes I think that nothing that ever comes into this house goes out. Things come in every day to lose themselves among other things lost long ago among other things lost long ago; lame wandering cows from nowhere have been known to be tethered, given a name, encouraged to get pregnant in the broad daylight of the street under the elders' supervision, the girls hiding behind windows with holes in them. Unread library books usually mature in two weeks and begin to lay a row of little eggs in the ledgers for fines, as silverfish in the old man's office room breed dynasties among long legal words in the succulence of Victorian parchment. Neighbours' dishes brought up with the greasy sweets they made all night the day before yesterday for the wedding anniversary of a god, never leave the house they enter, like the servants, the phonographs, the epilepsies in the blood, sons-in-law who quite forget their mothers, but stay to check accounts or teach arithmetic to nieces, or the women who come as wives from houses open on one side to rising suns, on another to the setting, accustomed to wait and to yield to monsoons in the mountains' calendar beating through the hanging banana leaves. And also, anything that goes out will come back, processed and often with long bills attached, like the hooped bales of cotton shipped off to invisible Manchesters and brought back milled and folded for a price, cloth for our days' middle-class loins, and muslin for our richer nights. Letters mailed have a way of finding their way back with many re-directions to wrong addresses and red ink marks earned in Tiruvella and Sialkot. And ideas behave like rumours, once casually mentioned somewhere they come back to the door as prodigies born to prodigal fathers, with eyes that vaguely look like our own, like what Uncle said the other day: that every Plotinus we read is what some Alexander looted between the malarial rivers. A beggar once came with a violin to croak out a prostitute song that our voiceless cook sang all the time in our backyard. Nothing stays out: daughters get married to short-lived idiots; sons who run away come back in grandchildren who recite Sanskrit to approving old men, or bring betelnuts for visiting uncles who keep them gaping with anecdotes of unseen fathers, or to bring Ganges water in a copper pot for the last of the dying ancestors' rattle in the throat. And though many times from everywhere, recently only twice: once in nineteen-forty-three from as far away as the Sahara, half-gnawed by desert foxes, and lately from somewhere in the north, a nephew with stripes on his shoulder was called an incident on the border and was brought back in plane and train and military truck even before the telegrams reached, on a perfectly good chatty afternoon.

THE LAST OF THE PRINCES : AK Ramanujan p.31

They took their time to die, the dynasty falling in slow motion from Aurangzeb's time: some of bone TB, others of a London fog that went to their heads, some of current trends, imported wine and women, one or two heroic in war or poverty, with ballads to their name. Father, uncles, seven folklore brothers, sister so young and lovely that snakes loved her and hung dead, ancestral lovers, from her ceiling: brother's many wives, their unborn stillborn babies, numberless cousins, royal mynahs and parrots in the harem: everyone died, to pass into his slow conversation. He lives on, heir to long fingers, faces in paintings, and a belief in auspicious snakes in the skylight: he lives on, to cough, remember and sneeze, a balance of phlegm and bile, alternating loose bowels and hard sheep's pellets. Two girls, Honey and Bunny, go to school on half fees. Wife, heirloom pearl in her nose-ring, pregnant again. His first son, trainee in telegraphy, has telegraphed thrice already for money.

Adil Jussawala

(b. 1940 schooling Bombay, 1957-70 England: architect, wrote plays;

Lecturer St Xav College 72-75; Lands End 72, just

publ. Missing Person)

FROM 'MISSING PERSON' : Adil Jussawalla : p.34

1 "No Satan warmed in the electric coils of his creaturesor Ganga Din will make him come before you. To see an invisible man or a missing person, trust no Eng Lit. That puffs him up, narrows his eyes, scratches his fangs. Caliban is still not IT. But faintly pencilled behind a shirt, a trendy jacket or tie, if he catches your eye, he'll come screaming at you like a jet -- savage of no sensational paint, fangs cancelled. 2 His hands were slavish; but fingers burst out from time to time to point to a fresh rustling of tails in the dustbin of history, a new inflexion of sails on the horizon. His thoughts were bookish; but a squall from the back of his skull suddenly fluttered their pages, making himm lose his bearings, abandon ship. His cock, less rulable than his rest, though fed on art-book types Hellenic forms, plumped on libraries circulating white bellies, white breasts, with a catch in its throat, jumped at nipples and arses of indiscriminate races and classes. His tongue, his one undergraound worker perhaps, bound by a sentence pronounced in the West, occasionally broke out in a rash of yowls defying the watch-towers of death, police dogs: a river of wild statistics; or in riddles crafted for cell-mates aspiring to doctorates from the Universities of Texas, Bogota, Bombay, perspiring students of socio-linguistics. [also 3-7]

Agha Shahid Ali

[belongs to Kashmir but spent most of his formative years travelling. After

having spent some years teaching English at [Hindu] college at Delhi, he has

been in the US on various teaching assignments. His first book of poems

Bone Sculptures, appeared from Calcutta in 1974.

This is his first appearance in an anthology]

see also: reminiscences by his niece, Ayeda Naqvi.

SHAVING : Agha Shahid Ali : p.40

In the mirror, the hand hacks at my skin It belongs to the child who used his father's blades for sharpening pencils, playing murder. Full of cuts, I have the blood-effacing instruments: water, water, and survival tricks : I'm as clean as glass, my brown face glistens with oil, turns a fine olive green. There's no return to the sanctuary of ripped paper-boat-journeys This is morning, I must scrub myself. A college lecturer, I smell of talcum Old Spice and unwritten poems. The mirror smiles back like a forgotten student: The hairs die like ants in the basin. My reflection gathers the night's dust, I wipe it with the morning towels. The girls drape their muslin shawls, their necks turn on Isadora's wheels: In the classroom I shuffle like unrhymed poetry The blade, wet with Essenin's wrist, waits with the unwritten poem.

STORM : Agha Shahid Ali : p.41

The rain dissolves its liquid bones Humming the wind, the lightning grazes the skin. A cloud descends : My eye is vapour, this, the dream's downpour: I must seal the tin-blue spaces. I glued some scraps, made a paper boat: Balancing a prophet's journey, the Great Flood in the bathroom sink, I was six years old: Mother, close the tap, Noah has hit the night, his Ark will sink. In the Atlantic's pariah-blue, there are no survivors; On the unsinkable Titanic, I'm left all alone; Ice-bergs hide their whale-teeth: I can't save Noah, God has picked his relic, beaten me to it: He wears Noah, a charm round His neck. On the empty deck, no life-boat left, my fingers capsize. My jacket is ice, I hold on to its cold, to anything. Mother, I'm alone, terribly alone.

K.L. SAIGAL: Agha Shahid Ali : p.42

Nostalgic for Baba's youth, I make you return his wasted generation: I know you felt it all: the ruined boys echoed through you, switched their sorrow on the radio: the needle turned to your legend. you always came with notes of madness, the wireless sucked your drunkenness: you quietly died, singing them to a sleep of Time Counting the ruins of decades, the boys were left, caressed with the air's delirium. Now two generations late, you retreat with my sanity, Death stuck in the throat!

LEARNING URDU : Agha Shahid Ali : p.43

From a district near Jammu, (Dogri stumbling through his Urdu) he comes, the victim of a continent broken in two in nineteen forty-seven. He mentions the minced air he ate while men dissolved in alphabets of blood, in syllables of death, of hate. "I only remember half the word that was my village. The rest I forget. My memory belongs to the line of blood across which my friends dissolved into bitter stanzas of some dead poet." He wanted me to sympathize. I couldn't, I was only interested in the bitter couplets which I wanted him to explain. He continued, "And I who knew Mir backwards, every couplet from the Diwan-e-Ghalib saw poetry dissolve into letters of blood." He Now remembers nothing while I find Ghalib at the crossroads of language, refusing to move to any side, masquerading as a beggar to see my theatre of kindness.

TAXIDERMIST : Agha Shahid Ali : p.44

First the hand, delicate, precise, knows how to carve where to take the knife, make more alive than when alive: No fur, no feather, I am only skin-deep, so easy to get to the cancer beneath: He fills me with straw, Yeats's tattered coat at twenty-five, (not the adolescent fancy-dress-scarecrow when I won the first prize!) No hurdle now, he reaches my hunger: I've never felt so full before! I scare eagles, the stuffed crows in his room; they escape me, freedom a synonym for the sky. Caressed by the leopard's vacant eye, finally warm, secure, in his skin, I turn towards the bloodless direction. The fan drones in my veins, blood humming like chopped air; my tongue hangs out, poems dead in its corners. Suave pimp of freedom, here I am, ready for your show-window: Will you now bargain for me?

Arun Kolatkar

[b Kohlapur 1932. works as graphic artist in Bombay. poems in magazines and anthologies since 1955. Jejuri pub. 1976 is first book. Recently won the Commonwealth poetry award. His translations of Tukaram have been widely acknowledged. influence on the work of young Marathi poets has been considerable.]

THE BUS : Arun Kolatkar : p. 45

The tarpaulin flaps are buttoned down

on the windows of the state transport bus

all the way up to Jejuri

A cold wind keeps whipping

and slapping a corner of the tarpaulin

against your elbow.

You look down the roaring road.

You search for signs of daybreak in

what light spills out of the bus

Your own divided face in a pair of glasses

on an old man's nose

is all the countryside you get to see

You seem to move continually forward

towards a destination

just beyond the caste mark between his eyebrows.

Outside, the sun has risen quietly.

It aims through an eyelet in the tarpaulin

and shoots at the old man's glasses.

A sawed off sunbeam comes to rest

gently against the driver's right temple.

The bus seems to change direction.

At the end of a bumpy ride

with your own face on either side

when you get off the bus

you don't step inside the old man's head.

THE PRIEST : Arun Kolatkar : p.46

An offering of heel and haunch on the cold altar of the culvert wall the priest waits. Is the bus a little late? The priest wonders. Will there be a puran poli on his plate? With a quick intake of testicles at the touch of the rough cut, dew drenched stone he turns his head in the sun to look at the long road winding out of sight with the eventlessness of the fortune line on a dead man's palm. The sun takes up the priest's head and pats his cheek familiarly like the village barber. The bit of betel nut turning over and over on his tongue is a mantra. It works. The bus is no more just a thought in the head. It's now a dot in the distance and under his lazy lizard stare it begins to grow slowly like a wart upon his nose. With a thud and a bump the bus takes a pothole as it rattles past the priest and paints his eyeballs blue. The bus goes round in a circle. Stops inside the bus station and stands purring softly in front of the priest. A catgrin on its face and a live, ready to eat pilgrim held between its teeth.

HEART OF RUIN : Arun Kolatkar : p.48

The roof comes down on Maruti's head Nobody seems to mind. Least of all Maruti himself. May be he likes a temple better this way. A mongrel bitch has found a place for herself and her puppies in the heart of the ruin. May be she likes a temple better this way. The bitch looks at you guardedly Past a doorway cluttered with broken tiles. The pariah puppies tumble over her. May be they like a temple better this way. The black eared puppy has gone a little too far. A tile clicks under its foot. It's enough to strike terror in the heart of a dung beetle and send him running for cover to the safety of the broken collection box that never did get a chance to get out from under the crushing weight of the roof beam. No more a place of worship this place is nothing less than the house of god.

THE DOOR : Arun Kolatkar : p.49

A prophet half brought down from the cross. A dangling martyr. Since one hinge broke the heavy medieval door hangs on one hinge alone. One corner drags in dust on the road. The other knocks against the high treshold. Like a memory that gets only sharper with the passage of time, the grain stands out on the wood as graphic in detail as a flayed man of muscles who can not find his way back to an anatomy book and is leaning against any old doorway to sober up like the local drunk. Hell with the hinge and damn the jamb. The door would have walked out long long ago if it weren't for that pair of shorts left to dry upon its shoulders.

A LOW TEMPLE : Arun Kolatkar : p.50

A low temple keeps its gods in the dark. You lend a matchbox to the priest. One by one the gods come to light. Amused bronze. Smiling stone. Unsurprised. For a moment the length of a matchstick gesture after gesture revives and dies. Stance after lost stance is found and lost again. Who was that, you ask. The eight arm goddess, the priest replies. A sceptic match coughs. You can count. But she has eighteen, you protest. All the same she is still an eight arm goddess to the priest. You come out in the sun and light a charminar. Children play on the back of the twenty foot tortoise.

THE HORSESHOE SHRINE : Arun Kolatkar : p.51

That nick in the rock is really a kick in the side of the hill. It's where a hoof struck like a thunderbolt when Khandoba with the bride sidesaddle behind him on the blue horse jumped across the valley and the three went on from there like one spark fleeing from flint. To a home that waited on the other side of the hill like a hay stack.

Bibhu Prasad Padhi

[b. 1951 in Cuttack. teaching at the Ravenshaw College, Bhubaneshwar. many poems published India and abroad... incl Dialogue India, poetry magazine from Calcutta, ed. Pritish Nandy (1969-1975). This magazine also published Jayanta mahapatra and Deba Patnaik for the first time in the early seventies. ]

RAINS IN CUTTACK : Bibhu Prasad Padhi : p.52

In the afternoons they whisper over the roadside fields round my waterproof room in crystal-cut forms. Their sharp, geometrical angles drain the needlethin leaves now weakened by the summer typhoid. Their rough and rocking fingers dishevel the chaste and religious casuarinas into bathing figures. Their cool and miraculous hands raise the shy greens in the dust brown grass under my feet, stretch them about me. Dear mother, if you will allow me I shall make the mudgreen carpet mine and make full use of it while the rains about me are whispering still.

Deba Patnaik

educated in India, England and the US. After teaching for a while in

Cuttack, has returned to the US, where he teaches literature, philosophy,

and photography. Till recently, consultant at Kodak Museum, Rochester,

now lives in Syracuse. Work has appeared in both English and Oriya.

DEATH IS NOT DYING : Deba Patnaik : p.57

Death is not dying. Waiting is. Waiting for a dead man to arrive. Not any man, but my father. I remember those endless railway lines stretching tediously like a golden-jubilee marriage. And waiting. For my father to return. Those trains that never brought him back when I desired him. Crossing those lines, fighting with the man at the level-crossing and sitting perched on an unaging indifferent boulder. Now I wait after thirty years, maybe thirtyfive, waiting here for the dead to come home. Who says death is lonely? Living is. Memory is a treacherous rainbow-arch to blind alleys -- unending, serpentine. Memory is a shadow-play tricking us into believing. Some day when my wife and I sit with our whitened hair, corrugated skin and a grandchild asks tell me granpa tell me about your pappa my wife will only blink, I know. and I'll whisper I know nothing.

THE CLAPPING OF ONE HAND : Deba Patnaik : p. 63

Love we honour as if we cannot live without. Words we cling to as if no meaning exists beyond. I will wait until love and word's time runs out.

AGAINST ALL SILENCES TO COME : Deba Patnaik : p.65

Silence fumbles on my lips like my mother's memory. They told me how she died -- her asthamtic lungs choked in coma. She still had a grin on her lips, her eyes all shut. So much like her -- she smiled into death. I do not accept her death. Nor my father's. Although I have learnt to live with mine. Lightning rips a soaked sky like a memory. Through this riot of rain creeps a silence. My room gets crowded -- shapes of silence, Jasmines, cactus, dark stars. And the face of a girl who once bared her sibling breasts on a nighted windy beach. I fight against all silences to come. Against the silence that wraps my typewriter. I pick up words. Throw them around. Memory and silences disperse like white pigeons in a storm.

Dilip Chitre

b. 1938 in Baroda. grad U Bombay, and has been a teacher,

journalist, sales promotion executive, advertising executive, magazine

columnist. Currently at the Intl writing programme at Iowa. He writes

in both Marathi and English, and translates.

His first collection of poems in Marathi appeared in 1960. Also a

well-known painter.

POEMS IN SELF-EXILE: Dilip Chitre p.66

The season's first dead butterfly Has freshly frayed wings. Meanings are transferred Like the wet on the grass To shoes. America is incredibly erotic. Too many legs makes all these streets sexy. Back home in Bombay, we have one single millipede Walking towards the city every morning. It is so hot there, and still, out of modesty, Those who afford wear all the clothes they can. And also, unlike here, those who have the money Eat without counting the calories. I am homesick, which is stupid of course. I was never a famous chauvinist back home, Nor is America not beautiful. But I am terrified Of such glowing youth, such exquisite innocence, Such exotic visions of the rest of the world, Which exists somewhere, That I feel already bsolete Not being American. Perhaps I should have been, after all, a guru, Or a yogi, a gigolo, a snake-charmer, or a cook Of clandestine curries instead of being a poet. America, here I come, too Late.

THE NIGHTMARE IS A PENINSULA : Dilip Chitre 67

The nightmare is a peninsula For it has water on three sides It reminds me of a certain land Giant, intricate and obscene Perhaps the womb I came out of For it has water on three sides And something alive stirs in the dark A million graphs are superimposed On a strange something underneath Or may be it was the place where we romped As children or een that erotic crowding of furniture Of the afternoon in a hot and dusty room For it has water on three sides Like the place where we first made love And that place where grandmother died Fire and with water on three sides Its called a peninsula I think Land or body or fire or thought With water on three sides I do not know what the water is there for Or the land for that matter But it certainly is a nightmare Because I woke up terrified with a parched throat As if I was face to face With a familiar ghost

TUKARAM IN HEAVEN; CHITRE IN HELL : Dilip Chitre : p. 71

The needle is expertly Jabbed into the vein; The innermost stranger Wakes up again. My mask has fallen, It grins at me: I go out forever On a faceless spree. In a milder light And a colder sun, Absent-minded, I reach for the gun. A whole country Is vanishing now; What's left of love Is my own forehead. The skull's architecture And the fading formation Of reticular frescoes I bequeath to you. I bequeath to you My fossil and my dossier. And I join the saints' Immortal choir. Tukaram in heaven, Chitre in hell, Sing the same song Centuries apart. Their bone derives From the same stone That stands erect at Pandharpur In the shape of a god Both gentle and rude And always Unmoved. The river flows by Like so many people, While this stance By itself is A spire And a steeple. History is dust In this kind of summer. The heat is The lasting truth. Man spreads His own rumour In the form of God To seize a creation Not his own. This kind of summer Is the brain's Own blaze. It is Vitthala who creates Sun and rain: Tukaram's joy And Chitre's pain Are two faces Of the same coin. Counterfeit and divine. The sovereign currency Of generations Standing In the same plain. Let us speak of God Since man cannot be spoken of: Let us infer from the image in stone The mind, the hand, the chisel, the stroke. For the Lord is the infinite Sleep from which we wake And, in grinning granite, We carve Him out of the night. Into His muscles We invest our souls; For his heart is of stone, His heartbeat our own. Our voices are hoarse with God: He is our scream, our cry, our moan, Tukaram in heaven, Chitre in hell, Tuned to the same truth, centuries apart. They dance in the same place And celebrate Sameness As the only art. Our voice is a village You have never visited, Where God lives In silent hunts. You have not seen His million faces; For God resides In uncivilized places. He is the hunger, And He is the food; He is the grain, The only good. God is crushed, God is ground, So thoroughly milled That He's never found. He is all we have From harvests to famines; It is Him we praise, And Him we curse. He is our neighbour, He is our enemy; He is our ruler, And He is our destiny. He is our slave, He is our landlord; But for our sword He'd hardly be brave. God is our village-- Idiot and sage; He is our convict And our judge. Him we worship, Whom we whip; On bent knees, It's Him we beat. He is our sinner, He is our saint; We begin in Him, In Him we end. Come pock-marked poets, Join Tukaram and Chitre, For the song of heaven Is one helluva chant. Ask, and you shall be refused; But do not leave Your voice unused. It's all you've got. Remember, our best Poems were always As bald as facts, As bare as these hills. Because our spirit Has aspects of stone, And because our stones Are lasting mirrors.

Gieve Patel

b. 1940 in Bombay. St Xavier's High School and Grant Medical College. Is a GP. First book, Poems, publ Nissim Ezekiel (1966). Just out: How Do You Withstand, Body (1976). Also written plays and a painter with several exhibitions

NARGOL : gieve patel 76

This time you did not come To trouble me. I left the bus Wiping dust from my lashes And did not meet you all the way Home. At the back of my mind, Behind greetings, dog-licks, and deepening Safety, I continued to look for you – But my strolls continues pleasant – I did not spot you at the end of a lane, Your necklace pendulant as your skin, Your cringing smile pointing out the disease: Leper-face, leonine, following my elbow As I walk past casual, casual. I am friendly, I smile, I am No snob. Lepers don't disgust me. But also Tough resistance: I have no money, **** BEGGAR Meet me later, My fingernail rasping a coin. She'll have her money but Cannot be allowed to bully – Let her follow, let her drone, Sooner or later she'll give up, Stop in the centre of a lane, Let herself recede. I reach the sea. Yes, that was essential. Discipline. In the open street I stand With elders. How far have you Studied, when do you finish? In the middle of my reply She passes by, I skip a word, she cannot Meet my eye, grins timidly, goes on; Accepted fact This is not the time. Afternoon, and she reappears, Stands before the house, says Nothing, looks for my eyes between page-turns. I cannot read. The book is frozen, angry weapon In my hand. I pretend a page, Then look up – I'm reading now I say, I'll give you later – switch down, Master, unquestioned. She goes. Cruel, you're cruel. From a village full of people She ahs chosen me; year after year; Is it need Or a private battle? At the end it is four annas – Four annas for leprosy. It's green To give so much But I'm a rich man's son. She cringes – I've worked for your mother. She hasn't – You come just once a year. All right, a rupee. She goes. My strolls are to myself again, The sea is reached with ease, Reading is simplified. One last tussle: Was it not defeat after all? Personal, since I did not give, I gave in ; wider – there was No victory even had I given. I have lost to a power too careless And sprawling to admit battle, And meanness no defence. Walking to the sea I carry A village, a city, the country, For the moment On my back. This time you did not come To trouble me. In the middle Of a lane I stopped. She's dead, I thought; And after relief, the next thought: She'll reappear If only to baffle.

UNIVERSITY : gieve patel : p.82

Is there reason to believe the students Of Dacca University were better Than those of our own? Need I repeat What I know so well from my college days -- The dull corridors, the vacous library, The children of the poor in Ill-fitting clothes skulking In corners, those of the rich Brilliant and febrile, their sparrow brains Ringing like jingles in their skulls? To be brutally shot, why not, is a kind of fate. -- And the professors! O professors, Stale, malodorous, with yesterday's coats And neckties! A small family Tucked away in the grimiest part of town Pitiful bank balance, tame sheep at home, At work holders of the flaming Mark sheet to terrify And subjugate monsters; And gently to amuse the affluent Who know them harmless and by their first Name -- freddy, eddie, peddie -- Safe toys to smile at for two years Before one puts away college And goodfellowship to join the beastly roaring outside. They too were shot. To the last threatening to fail the assassins. And why should I moan? Yesterday's chicken meal saw No less significant a slaughter. Can domestic fowl calculate Right done them from wrong? What Was butchered? Not a Fierce choir of learning. Not Any newness that ten years from now would Spread alluvial across a parched country. Students, Dolls emptied into untimely graves, May your odour rise and trip up Our brains. Tell us To change our thought.

ON KILLING A TREE : gieve patel p.84

It takes much time to kill a tree, Not a simple jab of the knife Will do it. It has grown Slowly consuming the earth Rising out of it, feeding Upon its crust, absorbing Years of sulight, air, water Ahd out of its leprous hide Sprouting leaves. So hack and chop But this won't do it. Not so much pain will do it. The bleeding bark will heal And from close to the ground Will rise cured green twigs, Miniature boughs Which if unchecked will expand again To former size. No, The root is to be pulled out -- Out of the anchoring earth; It is to be roped, tied, And pulled out -- snapped out Or pulled out entirely; Out from the earth-cave, And the strength of the tree exposed, The source, white and wet, The most sensitive, hidden For years inside the earth. Then the matter Of scorching and choking In sun and air, Browning, hardening, Twisting, withering And then it is done.

GOING HOME : Imtiaz Dharker : p.85

[ an MA in English and Philosophy from Glasgow University, spent

several years abroad before settling down in Bombay. works for

well-known advt agency. is the poetry editor for Debonair.

work has appeared in several magazines, journals, anthologies

This is her first appearance in an anthology of

Indian poetry in English. ]

I'll go. But let me close the windows

or the tunnel will come in.

The train nuzzles down the track

that leads back home. New landscapes

spread their legs.

Behind me, with the dregs

of rain, crows clatter for pickings.

They've made a feast of my going.

On the platform I

perhaps

could have squatted on passive haunches

among waiting women

who rake the day with their eyes,

rake the years for a hope

of home

as they comb the crows for fleas.

*

Fields become familiar now,

They tug at you between telegraph fingers

that warn you not to stray

from the approved track.

So now you know you're back.

Beyond your tidy grove

the hills arch to the sky.

Even crows rise

into a flight of rain.

Your mind pulls into its station.

Your past climbs in,

puts down its luggage

and looks you in the eyes.

*

Sometimes there were watermelons

split wide and wedding red

and fragrant

laughing at the greymouse english day.

*

At twelve

"not a mark on her, and pretty.

she'll never have an awkward stage"

his wrinkled white hand slipped down her back.

Mummy put me in purdah

or he'll see the hair sprout in my lap.

Mummy put me in purdah quick

or he'll see.

*

On the first day of the thirty

days of fasting, the other children

hid beneath the darkest leaves

to eat

soft bread white as their teeth;

giggling with guilt, breath quickening

on a furtive wing of heat.

The bread might have been [?night]

a thigh or breast in her mind

gorging on the pride

of first blood warm between her legs.

*

But did I say

these were not my gods?

Small eyes pink with craft, [?carft]

the china hands of dolls,

plump lips pursed to a flute.

A heavy rope of incense coils

around you. The fat gods

dig you in the ribs and laugh.

Sometimes you hear andother god

crackle from a single singer's throat.

Birdflight raises a minar

that tickles the sky into smiles.

Distance is not made of miles.

*

Her mind rewinds

the ghazals and punjabi songs,

The camera behind her eyes

watches as she trails dupattas;

dancing

she is the heroine

of films that come from home.

The reels spill out bright fields of maize

that flirt with her

through the dingy town.

*

It was easy to hate (from the tenements)

the ones in the house on the hill.

"They'll come to no good,

daughters higher-deucated, mixing

with belaiti boys. They'll regret it."

Yes, they will.

Their heads come rolling down the hill.

*

Making love. Going home.

Both start with open arms

and a festival spills out.

Your name is scattered,

shattered brightens blinds you

winding round the black holes of your eyes.

Fatelines crack open till the sky

looks through.

Why did you leave?

Why did you come back?

You try to fill the crevices with smiles.

Get down on your knees.

There must be some tenderness

in the splinters of the violent act.

*

The house is lit up.

The door thrown open.

Your dead mother waiting

at the top of the stairs.

*

I have caged myself inside a stranger's head.

But if you were to open

wide the door, I would not go.

Lovers and forsaken fathers know

the flood will well in them,

find the sun, and dry

to simple stone.

So even if I try the world

and find it wanting

daddy

how can I come home?

Jayanta Mahapatra

b. 1928 in Cuttack, lived there since. Writing seriously since 1968. Awarded Jacob Glatstein Memorial Award from Poetry Magazine, Chicago. In 1975, attended the Intl writing programme at Iowa.

NOWHERE : jayanta mahapatra : 89

Where does nowhere lie? inside the thought of compromise [?nside] that keeps moving ahead of us? Or is it a dream which never reveals? Is nowhere an empty room rising like a god flapping up into the sky? Its great cloud beyond the silent hands of hope? The nowhere in me stops short in the middle of a sentence. It reaches. Where my heavy hands hold each other behind my back, as I pace my room, waiting, listening; slumped in the shadows of another summer. [ ... ]

THE COMING OF WINTER : jayanta mahapatra : 90

Mists out of darker nights. Spiderwebs warp the grass, a cold hand on temple spires. An cow's pink full teats, the year's new potatoes dug out of the earth: faces of old friends. Morning a longing in my wife's votive eyes. High above, in the shadows of our thoughts, bird-beat, the steady throb of survival, of a bird migration going south. Instincts weaving in and out of the sun. And in the tremblings of the earth a woman walks slowly, past the last summer that wells out of the shadows of her home, an unsuspected tender laugh on the mists of her eyes.

GRASS : jayanta mahapatra : 92

Have I to negotiate it? Moving slowly, sometimes throwing my great grief across its shoulders, sometimes trailing it at my side, I watch a little hymn turn the ground beneath my feet, a tolerant soil making its own way to the light of the sun. It is just a mirror marching away solemnly with object and earth, lurching into an ancestral smell of rot, reminding me of secrets of my own: the cracked earth of years, the roots staggering about an impatient sensuality, bland heads heaving in the loneliness of unknown winds. Now I watch something out of the mind scythe the grass, now that the trees seem to end, sensing the almost childlike submissiveness; my hands that tear their familiar tormentors apart waiting for their curse, the scabs of my dark dread.

THE BEGGAR TAKES IT AS SOLACE : jayanta mahapatra : 93

He watches the coin in his palm floating as if it has wings he turns weak a rain riddling the earth of his body he looks up again his noisy palm curls into a fist he sees people everywhere the future getting paid mapped space moving then opening his fingers a mouthful of time as he tries to swallow it some stone this aged cry around his neck and yet his dreams like birds plummeting seeing and unseeing roots of his shriven tree of demand as he watches a hand like an orange sun reach out from an automobile window and drop one of his quaking days and pass by passing the curled up leaf of its time.

THE INDIAN WAY : Jayanta Mahapatra 95

The long, dying silence of the rain over the hills opens one's touch, a feeling for the soul's substance, as for the opal neck spiralling the inside of a shell. We keep calm; the voices move. I buy you the morning's lotus. we would return again and again to the movement that is neither forward nor backward, making us stop moving, without regret. You know: I will not touch you, like that until our wedding night.

Kamala Das

b. 1934 in Punnayurkulam in Southern Malabar and lives in Bombay. Writes in English and Malayalam (Kerala Sahitya Akademi 1967). Has won a poetry award from the PEN Phillipine Centre and the Chaman Lal Award for fearless journalism. Three books in print [Summer in Calcutta_ (1965), The Descendants (1967), The Old Playhouse and Other Poems (1973),] and a controversial biography. Has done a book with Pritish Nandy - Tonight, This savage rite, selection of love poems.

GHANSHYAM: Kamala Das

Ghanshyam, You have like a koel built your nest in the arbour of my heart. My life, until now a sleeping jungle is at last astir with music. You lead me along a route I have never known before But at each turn when I near you Like a spectral flame you vanish. The flame of my prayer-lamp holds captive my future I gaze into the red eye of death The hot stare of truth unveiled. Life is moisture Life is water, semen and blood. Death is drought Death is the hot sauna leading to cool rest-rooms Death is the last, lost sob of the relative Beside the red-walled morgue. O Shyam, my Ghanshyam With words I weave a raiment for you With songs a sky With such music I liberate in the oceans their fervid dances We played once a husk-game, my lover and I His body needing mine, His ageing body in its pride needing the need for mine And each time his lust was quietned And he turned his back on me In panic I asked Dont you want me any longer dont you want me Dont you dont you In love when the snow slowly began to fall Like a bird I migrated to warmer climes That was my only method of survival In this tragic game the unwise like children play And often lose [? lose in] At three in the morning I wake trembling from dreams of a stark white loneliness, Like bleached b0ones cracking in the desert-sun was my loneliness, And each time my husband, His mouth bitter with sleep, Kisses, mumbling to me of love. But if he is you and I am you Who is loving who Who is the husk who the kernel Where is the body where is the soul You come in strange forms And your names are many. Is it then a fact that I love the disguise and the name more than I love you? Can I consciously weaken bonds? The child's umbilical cord shrivels and falls But new connections begin, new traps arise And new pains Ghanashyam, The cell of the eternal sun, The blood of the eternal fire The hue of the summer-air, I want a peace that I can tote Like an infant in my arms I want a peace that will doze In the whites of my eyes when I smile The ones in saffron robes told me of you [? is saffron] And when they left I thought only of what they left unsaid Wisdom must come in silence When the guests have gone The plates are washed And the lights put out Wisdom must steal in like a breeze From beneath the shuttered door Shyam o Ghanshyam You have like a fisherman cast your net in the narrows Of my mind And towards you my thoughts today Must race like enchanted fish...

A MAN IS A SEASON : Kamala Das : p.99

A man is a season, You are eternity, To teach me this you let me toss my youth like coins Into various hands, you let me mate with shadows, HYou let me sing in empty shrines, you let your wife Seek ecstasy in other's arms. But I saw each Shadow cast your blurred image in my glass, somehow The words and gesture seemed familiar. Yes, I sang solo, my songs were lonely, but they did Echo beyond the world's unlighted edge, there was Then no sleep left undisturbed, the ancient hungers Were all awake. Perhaps I lost my way, perhaps I went astray. How would a blind wife trace her lost Husband, how would a deaf wife hear her husband call?

APOTHECARY-I : Keki N Daruwalla : p.104

(b 1937 Lahore, IPS. Under orion 1970,

Apparition in April 1971, Crossing of Rivers mid-70s)

A solemn mask on a liquored-up face

looks incongruous. Why not rip it off?

That's better ! Sit down, man! Smile once again!

You don't have to stand there

and cough discreetly and shuffle about.

You haven't come here to condole ! All is well

in my house-thank Allah for it who keeps

the obituary-scribe from the door

Yes, yes, I understand the death of a patient

is also a death in our family;

A part of me dies with him.

But this boy from Sarai Khwaja complained

of an ear-ache. I'd not seen him before.

Some ear-drops I gave him and forgot about it

Till that ekka stood at my door in the evening.

`He's thrashing around like fish... a stomach-ache...

he just can't bear it...'

"An intestinal knot maybe," I said, and when

I reached the village he was already dead,

his mother looking at me as if I had knifed him.

For this week past I face an empty room, swatting flies.

All my patients come from Sarai Khwaja,

Sarai Mir, Allahdadpur, Kusum Khor,

Five miles on ox-cart and mule-back they come

but now they shun me as if instead

of powders I dole out cholera and pox!

If a man comes to his lawyer for advice

and is murdered on his way back

will his clients abandon him? Never!

But a Hakim turns leper! They won't even read

the fatiha on my grave!

There is no logic to it, it's just there.

As there is no logic to a child

with an ear-ache in the morning

dying by evening of a stomach ailment.

Faith is all very fine. It is one thing to say, 'All this

is the acquiescence of clay to the will of the Lord*,

and drain your philosophy with a nightcap,

and quite another to face a hangover and

an empty clinic in the morning.

My uncle is paralysed Allah is merciful

or what would he have said to this

my only patient in fifteen days dead!

What does the pedestrian think of it,

Hakim Rizwan-ul-Haq

son of Irfan-ul-Haq

Hakim-ul-Mulk, Physician Royal to the

Nizam of Hyderabad reduced to this?

I know what you are thinking of:

the cars lined on the kerb outside

patients spilling out into the streets

from that homeo clinic across.

He is a widower and keeps

two good-looking compounders.

He tackles a serious case by ramming home

penicillin in the thigh

and a suppository in the rear*

Homeo clinic you call it!

You said something, did you,

Brother-healer did you say? Hippocrates?

A homeopath keeps two handsome

adolescents as his compounders.

Now where does Hippocrates get into the act?

He promises his clientele prophylactic doses

against typhus, measles, chicken pox f flu.

There isn't a plague in the slimy bogs of hell

which Doctor Chandiram, gold-medallist, can't stave off

with one of those powders of his!

Pardon me, for I got carried away.

We all pad the hook with the bait, Allah downwards.

What is paradise, but a promissory note

found in the holy book itself? And if you probe

under the skin what does it promise us

for being humble and truthful, and turning

towards Kaaba five times a day,

weeping in Moharram and fasting in Ramadan?

What does it promise us except

that flea-ridden bags that we are

we will end up as splendid corpses?

Keki N Daruwalla

b. 1937 in Lahore education Govt College Ludhiana + Punjab U. Currently lives in New Delhi, where he is in the Indian Police Service. His works include Under Orion (1970), Apparition in April (1971, UP State award), Crossing of Rivers, just appeared (1976), [Swords and Abyss (1979)]

THE PROFESSOR CONDOLES: Keki N. Daruwalla

Your brother died, you said? Eleven years old and run over by a car? I am so terribly sorry to hear it. Pardon me, not tragic, as you said just now. Unfortunate is the word, terribly unfortunate. Nothing could be more ... more unpleasant. But ‘tragedy is clean, it is restful, it is flawless’, as Anouilh said. This was an accident ... depravity of circumstance. There was no air of design about it, you follow? I cannot stand an accident, the blood clotting on the tarmac, the brain spilling over like an uncooked stew! The moment I see a crowd thrombosed around a victim, I take a detour to forestall a physical reaction. Tragedy is different, one aesthetic layer on the other to absorb the thrust, with neither desire nor revulsion aroused. But you need time, perspective for the action to evolve, and space -- that is essential for tragic momentum. I see your point, yes, the empty street, a car hurtling at 60 miles an hour. But that was not the momentum I was referring to. The Catastrophe must have a specific reference to us ... I can imagine your feelings ... yes, yes he was your brother, his death had a very personal reference to you. But there was no sin, no guilt no hubris no hammartia. Tragedy is a culture by itself. It takes a lifetime to be immersed in its panoply and symbol. Sometimes, of course, I brood: tragedy is no longer what it was. Its sweep and passion took in half the universe once. Evil came rasping like a magnesium flare into a night canopied with mirrors, and heavy with destiny, loaded with the past, the sky collapsed. But after the havoc, across the umber-coloured scraps of mist, horizons appeared awash with light and pencilled with pearl-grey monotones. But now there is no order to revert to, no sanctions beyond immediate hungers. And suffering would be a waste, like digging a canal from the desert to the river, only to find it as dry as the udders of an old cow. Tragedy today is private, insular: a depraved enzyme in the belly of chance. It digests you skull, hair, dentures and all. Yes, in an absurd scheme of things accidents are the order. I am sorry, extremely sorry, young man for the tragedy that overtook your brother, and left you with this grief you won't know what to do with.

Mehar Ali, the keeper of the dead : Keki N Daruwalla : 114

In the year of the fire-serpent, the prophecy runs lightning will chop the cummulus into chunks of meat. Red rain will fall as the goddess descends, her rain-red hair streaming backwards in the wind, to cart away the dead in the folds of her mists. It is a Tartar cemetery; they had lost their way across the roof, past serac country and the ice-falls, till coming to this cluster of low cliffs they flopped, savaged upto their knees by frost. Two of them survived and had this catacomb hewn out of limestone cliff; married Bhot women and begot children who wilted — nine generations scorched like dying melons on a withered vine. And now with a face like a patch of fissured bark and eyes: pools dulled with a film of moss, Mehar Ali, the keeper of the dead, remains the last of the living, his days slowly embering into ash. His speeches is a monotone that creaks on like a cartwheel going over gravel. 'This is the catafalque where lies Barqandaz, the wolf-slayer. The two survivors lie here and these their Tibetan wives.' A match flares across the vault. 'This miniature on the wall,look at the faces - each smaller than a match-head — and the paint-effect, like hairline-fractures on a cartilage. It is deliberate, to show the action of frost as it worked over their visages when they crossed the pass. The faces were done in old paint which cracks; the rest was done in vegetable dye.' The Californian females ask: 'Wolf-slayer? Where did he slay the wolf?' 'Mr. Mehar Ali, do you trace your lineage back to Jenghiz Khan?' 'Its amazing this Muslim cemetery in a semi-lama country! And this local prophecy, do you think the goddess will ever come?' There is no response In the past year he is known to have smiled only once when he mistook a flowering shrub for a child and blessed it. But when high winds moan, driving the rain into the catafalque, and lightning rends the sky, speech starts fermenting in his mouth and bursts out in bee-stung incoherence. It is then that he communes with the dead, they say, and his eyes probe each wraith of mist for the sky-woman, her hair flaming red as she alights upon the shroud-grey skin that keeps him whole — Mehar Ali, the keeper of the dead!

THE RADHARANI OF THE HEVAJRA TANTRA : Kersy Katrak

(b 1936 advertising. two vols of poems)

Was it my Lord as you imagined

Caught in your nightlong dream

Frozen and involute and contempating

The secret movement of your juices like a Yogi;

Before your suns had risen and she had borne you

Her bright effulgent holy children;

No, in the darkness while you held your blood

Secret as snake, all diamonds of the night

Glittering the age-long hood, and she coiled her length

Virgin to your perfect body, while her recurring dream

Excessive as your heat, rubbed and fondled

Your black forked stick to lightning, my Lord

Was it as you imagined? Was the real thing

Waking not less than dream?

For if your answer is yes,

However given, however dimly thrown my unseen way

In dream or gift or prophecy

Then so is mine yes also. [? in mine]

Not yet articulate, not able to pronounce my Om,

But stuttering and inchoate, wrestling my blankets

Of sleep like hoods and cauls and shrouds, all [caul- membrane of embryo]

Sweat and malformed struggle, underwater

Open my mouth and say it

'Yes' or 'Yeth' or 'Yef', whatever comes

Syllabic or no, echo your victory.

Often struggling for my hump

My humped and crippled sainthood, I envision

Your blood that warms the world, the flood

That purifies the sins of your good child.

But if you push me further Lord...

Then give me more than random blood: reveal

The secrets of your sperm,

The coiled luxury, the scented snake.

For I have tested my excesses and in the bargain

Bred the most perfunctory children.

Bright sunlit hands turning to monsters;

From what unguarded guilt

Stored in the liver, what secret revulsion

Of the beloved flesh, what glut of old remorse

What swarms of cowardice and love betrayed.

O apprehension of my father's father :

There is no paradise in seed :

All childhood on my head.

But if you answer no, then knife me dead.

O jacknifed on your book my Lord and O my Lady

Broken in your belfry where the monsters swarm

My nightly dream, spider and octopus

Betrayed by ditch and hag in a month of blood.

Playing with golden girls in most unreal

Blue glossy urinals. Each toy and plastic teat

Precursor of the wind that sweeps my home

Pre-empting al the carrion in my blood

Defining every small and real death :

The coil of flesh rising to small

Baffled erections in the light :

Smell of Balmain and sainthood in her dugs [dugs: teat, breast]

Churns my recurring night. [Balmain: fashion designer; perfumier]

But was it perfect Lord when you awoke

At your first kiss? A galaxy of broken

Empires flood my limbs. Sun upon sun

The Neptunes of desire,

All lust caving my limbs, my shrines bereft

The nightstreets of my wife deserted,

My mother's mother's blood smearing like servants,

My mind forming like holes. Assure me now

My friend and worker of my blood : you Alchemist :

When She arose, Rose of the World

And Queen of all your gardens

And kissed you on the mouth alone :

Did glands of honey burst within her throat

And flood your mouth with love,

Her sweets unbearable to hold : O you

My secret and most hidden Friend:

When your first bird had flown?

FOR ADIL AND VERONIQUE: Kersy Katrak : p.119

If after the frantic convulsions, Daily bread debacles, lovers' misunderstandings, Penis failures, Parsee Catholic epiphanies, Sweat and sulking, the coils of flesh part slightly And reveal the little Love God Small and winged and almost too delicate To survive the light of dawn you see him by : Will the gain measure up To the firm light of day Acrid breakfasts, taxis, offices and whores? Will the authentic bitter-sweet melody Caress your halfasleep dawn heads, The correct tingle hopscotch up your spine? For consider that we too have practised This ritual. I too daily beat my Hindu wife Daily she makes me pay. And every night, or every other, we discover This dark God in his cave Between linen and flesh pay homage. Renew, refresh the small tides of our being In all that passes for love. For consider how little the loss: A little journalism is washed away A little current sensibility Floats into the eternal A small reflex of intellectual grit erodes Self-control crumbles, accuracy flounders and sinks into the sea which after all Is never self-controlled and hadly every accurate. And consider the gain: white roseflesh And a small manhood struggling in the dawn sea Almost triumphant.

THE KINGDOM OF DESPAIR : Keshav Malik : 121

(ed Calcutta, Srinagar, worked for a while as asst to

J. Nehru. editor Indian Lit from Sahitya Akademi]

How far can you go

In the kingdom of despair

On fear and only fear?

No movement of soul can there be

Free like Icarus winging towards the bright star.

Nothing heard but a plaintive bird

Crying out in utter wilderness

Or a child shedding tear on tear

Lost in the tall elephant grass somewhere.

How far can you go

Where is fear and only fear,

In the dark kindom of despair?

IMPORTANCE: Keshav Malik : 123

[Malik was educated in Calcutta and Srinagar; worked for a while as asst to J. Nehru. editor Indian Lit from Sahitya Akademi] To sense what is and what is not of importance [?and what not] Is of some importance. Your double in the mirror, for instance Has little substance [a bit Ogden Nashey] Except a double double in a doting eye's transparence And there rediscover self anew in a taking tense (As distinct from the mere mimicking presence). And be broken your long sleep or trance In your body's ambience, A double gives offence. No, not you but it makes sense, A sky of stars, more stars, of suns -- That vast inheritance; Hence, Look up and reclaim your lost innocence.

M.F. Husain

b. 1915 in Pandharpur. One of our best known painters, awardwinning film maker, and widely published poet. This is the first time his work is included in an anthology. His visual experiments with poetry have been published in his book Poems To be Seen. Film Through the eyes of a painter awarded Golden Bear for best short film at Berlin 1967. Lives in Bombay and travels widely.

POEMS: M.F. Husain

I The feet nailed on earth Are never tired. To follow The roaming echo... Echoes once treasured Behind caves and carvings. Blown up rocks Have not returned. Though Flooded passenger trains Keep on shuttling... Making deep grooves on earth. Millions pour in Grooves deepen Trains snail down Layer under layers, Till the pores are blocked. But the roaming echo Knocks on The closed window. (noted artist, b 1915 Pandharpur)

Mrinalini Sarabhai

one of our distinguished classical dancers. Her first book, Captive Soil,

1946 was a poetic play about independence struggle. Novel

This alone is true pub London and Hind pocket books.

Also books on Indian dance.

Her most recent book Longing For The Beloved interprets the songs of

Shiva as related to Bharat Natyam.

Lives in Ahmedabad, runs Darpana, a school for performing arts.

ANANDA: Mrinalini Sarabhai

I fell on the steps. Tense. Bewildered. Running away from crowds. From hatred. From relationships. Escaping from condemning eyes. Seeking oblivion, searching for peace. The sacred hill. There I ran. Climbing desperately. Knowing only that I must. Through the thickness of bushes. Thorns. The steps are cold. Purified by many feet into accepted brokenness. Hard marble steps. Yet comforting. There was no pretene. Where did I want to go? What did I need to discover? From bondae, to truth. Just to natural. My self. Peace. Serenity. ... Through the mist I saw him. His face like that of Padmapani on the old wall of Ajanta. The thick lowerlip The petal like eyes. Come. He spoke. You are tired. No questions. Nothing. The simple food. A room. Warmth within and without. For days I sat looking upon the beauty of the mountain peak above me and the small white temple within it that sheltered me. He was part of that grandeur. In his silence I regained my faith. Sometimes he sat by me. Sometimes he spoke. Do not go on looking. It is there. Why do you long for what you are? When he lit the evening lamps for Devi I wastched his face. Calm, Unafraid. Early before dawn I awoke to his prayers. At night he was near. Like a child I was comforted. Only his presence. It was enough. One evening. Don't I said. Suddenly. Laughing. Disturbed within. Don't make me dependent upon you. He walked away then. Angered at what I said. Or hurt. Can one never be honest with anyone? I wanted him. Not in lust. But to possess him fully. Not him. His quality of peace. Or did I want to break that? The forest was thick with shedded leaves. The spring waters were sweet. I bathed in the coldness of the water. My long hair dried in the sun. With the sandal paste of worship I rubbed my skin. And in the twilight I waited for him to come to me. For I knew as he did, there was only the deep moisture of the earth beneath us and it was as though we became one with the sky, the dusk and later, much later, the stars. Between him and me there was Only peace and gentleness. Unravelling the mystery of the universe. The hill of the Goddess. Yes that night I was her. And he was the worshipper. As he kissed my body, as it became one with his, there was a ritual to our oneness, as thogh Shiva embraced Kamakshi. And spoke to her even through the act of love. It was on these enchanted moonstar evenings that I learnt the meaning of existence Even when he was within me, totally lost. He would say can you understand now what oneness is and togetherness? Say: Yes. Yes. Our sages told us but we do not understand. Ramas Radheshyam Shivashakti. ANd then the world would spin for us or, wat it that we made the worlds turn. He did. Ananda Ananda Ananda. Your name is bliss. You are bliss. ... pilgrims came to worship Devi. Climbing the steep hill slowly. ... Till one day I lit the lamps and opened the doors of the inner shrine. Ananda sat there. Like the stone image of Devi he too was immobile. The same smile upon both. The smile of Isvara. And I knew it was the moment of separation. I knelt at his feet. His hand lifted in the Abhaya mudra, his eyes looked into mine. Compassionate. Loving. Distant. From his feet I scraped the dust. Mutti, Vibhuti. I touched it to my forehead. And I went down the Steepness of the hill. The pilgrims passed me. Climbing, climbing. Ananda Ananda Ananda. (F play Captive Soil 1946, novel; poetry book: Longing for the beloved)

Iktara - Songs of the mendicant poet: Pria Karunakar

(F b. 1946 Calcutta, schooled at Simla. Vassar college)

Kaun gali gaye Shyam?

********************

I am a battered fruit in the hawker's basket.

Kaun gali gaye?

I am the relic in the stupa.

I am the Traveller at the cross-roads.

Kaun gali?

I am the cross-roads.

Gaye Shyam?

Shyam? Dark one?

As the flight of egrets

By the railway track

Fade pale into the red sky

Darkness falls, darkness falls

Down this gali

Quickly, quickly

Find the throne...

Down this gali...

The hooded watchman

With his lathi

Taps you on your shoulder Kaun?

Pulling on your beedie

Your earthen khuller cracks

And smashes to galactic fragments

On the railway tracks. And so

Between earth and earth

I came

To a pyramid

stacked high with lean bones,

Lean-shanked dancers

Chalked white, smudged nervously alive

With burnt cork and sindhur

Close to the skull, teeth

Smeared with rouge,

In sodden paper clothes

Whose paint ran in the rain :

These children of the poor

Gauded bravely towards

Death's bridal.

Still and heavy-lidded

In the stilled chauk of Night,

Paupers and vagrants.

Kaun gali gaye Shyam?

********************

I am in love with a tough inevitability.

I am in love with the River that changes and is still

The river.

********************

I will give myself to the stranger.

I will hide myself from the beloved

In many veils.

Shyam?

Shyam? It was a full moon

Over the river

As the children danced the raas.

Dogs howled as we entered

The white city and the karais

Seethed with milk

Painted into dreams

The little boys

Gestured and bowed

In antique Braj,

Voices like small pipes.

And the old women and men

Rocked and cried

Remembering Krishna.

The river ran dark with pale gleams,

Krishna the butter-stealer

The irresistible;

The Laughing Lover

At the trysting place under the trees,

Anachy in the blood.

Earthen gharas loosing milk

Under the well-aimed stone,

Hearths overturned and infants in cradles

Left crying and swinging

As the sound of anklets disappears

Into the woods... The river ran dark.

There is the sound of the flute

Carried on water; the sound

Of piping like water quickening

Through a hollow reed.

Flash of a blue throat,

Peacock's feather, flash

Of a turmeric-coloured dhoti

And a cry; A low laugh.

A wet ruby quivers on the grass.

Later the sun sees

Smashed foliage

And a dead-brown smear

Where soon the hoof falls

And the steaming dung.

In the summer the earth cracks open

Gaping with sore mouths.

The river shrinks.

The woman nags and scolds.

The man returns from office

Older. The price of milk goes up

By the bottle. Cows are tubercular

The shift to the city was hard.

The brother-in-law is doing well

As a railway cleark but now

Refuses to recognize

His relatives.

It could be worse.

Stacked vagrants under bridges

Sleep side by side for warmth

(Till the Municipality decides

To Beautify the City for a visiting official)

Wring out their guts with vile grease

And spit blood like paan-juice.

Kaun gali gaye Shyam?

Shaym?

Five daughters

And where is the dowry to come from?

Retirement due and no pension.

Brother it could be worse.

Is someone laughing in the street?

It must be someone of loose character

Wait. Did you hear a cry?

Quick, turn your head and scurry by.

What does it matter if one more dies?

Don't we all die like flies?

You may lose you job in the morning.

Under the street-lamp the mendicant singer

Sees the Lotus-Foot palmed tender ad the dawn

Tread silently and disappear

Like a panther into the ageing night.

[...]

Pritish Nandy

b. 1947 Calcutta. Poet, photographer, and graphic artist, is the auther of over thirty books of poetry, photography, and translation. His poems have been filmed and set to music. Heinemann have published his selected poems. Has received the Padmashri. Poetry editor of Illustrated Weekly of India and member of Sahitya Akademi advisory board.

THE NOWHERE MAN: Pritish Nandy

p.155-163 1 Come, let us pretend this is a ritual. This hand in your hair, your tongue seeking mine: this cataclysmic despair. Let us pretend tonight that you are mine. Forever. For when daybreak returns, we shall realise once more that forever means an empty room, a tired night swirling into nowhere, when I shore up to your tattered skyline. 2 At midnight I move in on strangers, for the caress or the kill. I have come to terms with shadows, I have been assaulted by gentler lovetimes : once in a long while a face comes near, our eyes meet in challenge, or is it love? Our bodies come alive in secret oneness: one spring ago, terrified to be touched, you draw me tonight, at last, deep within your frantic countryside. 4 The wind disentangles itself from your frenzied body as hurricanes of dreams follow me: eternity is only a river reaching towards the sea. My tongue travels to your navel, and downwards : I cling to your body, my mouth breathes in the shadow of your breath. Someday perhaps the sea will reveal itself, the delirium of the flesh fatigue at dawn. 11 It hurts to say I am sorry. So let us use unfamiliar words. The summer has gone the ground's turned cold. The old road calls me back again. Anothertime we shall meet again: as strangers or as friends, or perhaps as lovers once again. Now turn, turn, to the rain again. 15 Tonight I draw your body to my lips: your hand, your mouth, your breasts, the small of your back. I draw blood to every secret nerve and gently kiss their tips, as you move under me, anchored to a rough sea. I cling to you, your music and your knees. I touch the secret vibes of your body, I fill my hands with the darkness of your hair. This passion alone can resurrect our love. (b 1947 Calcutta. Poet, photographer. Padmashri, poetry ed Ill Weekly)

Rakshat Puri

b. 1925 Lahore. In the fifties he came to journalism and from 1956 to 1861 was correspondent at New Delhi for The New Statesman of London. Now an asst editor with Hindustan Times, went to Indo-China during the war.

This And That : Rakshat Puri : 163

Not this, not this, nor That, not also the other, Beneath the rose, thorns. The sunflower assumes The sun, night the day, and all The seconds, epochs. Dark beneath the rose Shadows upon this, upon That, beneath the rose Time congealed, congealed Revolutions, epochal Between this and that. The glass in the eye, Sun high at noon, day, night, eseeing Nothing in the sky. Between the rose and The sunflower, assumption sits On this, that, other.

RAIN: Rakshat Puri p.164

On the lake the rain Brings an explosion of ripples. Ill luck breaks mirrors. The rain tears summer To ribbons and patchwork days Cover frail autumn. Then dust walls dry leaves To the lake nursing a patched Sky in its cold ruins.

A HYMN IN DARKNESS : Randhir Khare : p. 169

(b 1948, many years in Cal theater, book of poems: Hunger)

why do you grow flowers in

the void that divides us?

flowers with white stems

and faces of dead children.

their roots such silence

from cavities of last night's

teeth sunk in yellow gums

your flowers smell of pain,

lost years embedded in mud --