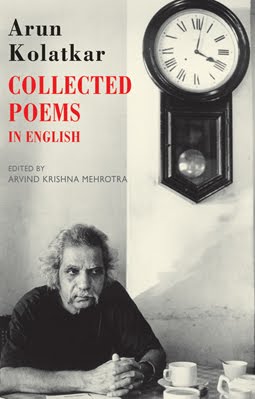

Collected Poems In English

Arun Kolatkar and Arvind Krishna Mehrotra (ed.)

Kolatkar, Arun; Arvind Krishna Mehrotra (ed.);

Collected Poems In English

Bloodaxe Books, Feb 2011, 383 pages

ISBN 185224853X 9781852248

topics: | poetry | indian-english | single-author

Enchanted by the ordinary, Kolatkar made the ordinary enchanting. - Arvind Mehrotra, introduction p.23

The main attraction of this volume for me was the inclusion of the posthumously published collection of poems, Boatride and other poems, edited also by Arvind Mehrotra. This is the largest of the four volumes in the book, and has poems in English that appeared in various small magazines, a number of translations from Marathi, including a selection of his own Marathi poems. The translations reflect an ambiguousness typical of Kolatkar:

Translating a poem is like making love

having an affair

Making love to a poem

with the body of another language

...

it follows that translating your own poems

is like making love to one of your own daughters

it ought to be a cognizable offence

taboo

carry a stigma

there ought to be a law against translating your own poems

(unless the law against incest already covers it)

The volume has a section called Words for Music, which were meant to be

songs (Kolatkar took guitar lessons and even recorded some of these). He

was a long-time fan of Blues music, and once had a large collection of

blues records. Arvind mehrotra suggests that there is an affinity of

spirit between many Blues lyrics and Tukaram; each speaks in the idiom of

the street. (AM: also there is an irreverence towards established power

structures). For instance

It's a long old road, but I'm gonna find the end.

It's a long old road, but I'm gonna find the end.

And when I get there I'm going to shake hands with a friend.

could just as well have been Tukaram, though it is Bessie Smith. [p. 30]

The section had been titled Drunk and Other songs by Kolatkar, and

includes several vagabond poems:

it's only eleven were you asleep o well

at least i didn't ring the wrong doorbell

thank god i found your place i been here before

but it's dark outside one can't see the name on the door

i was wondering if you'd let me stay the night

i haven't eaten all day i could do with a bite

AKM discussed these poems with Kolatkar - most of them, he says, were written

when he was "straight drunk".

Excerpts: Poems in English

Teeth p. 227

Lord I am revealed How my teeth gleam My sides ache. My forehead Yawns. I have unlocked Like a monstrous Pomegranate. Do not Touch me God do not Come near me, for all Is grist to my grinding. My loin has bared its teeth. My thighs open like iron Maidens. Guts whip out. My nose crawls over me Like a prehistoric Lizard come back to life. My throat nibbles at my Tonsils. And I grin Having chewed off my lips.

Poems in Marathi (translations)

Pictures from a Marathi Alphabet Chart p.259

Pineapple. Mother. Pants. Lemon. Mortar. Sugarcane. Ram. How secure they all look each ensconced in its own separate square. Mango. Anvil. Cup. Ganapati. Cart. House. Medicine Bottle. Man Touching his Toes. All very comfortable, they all know exactly where they belong Spoon. Umbrella. Ship. Frock. Watermelon. Rubberstamp. Box. Cloud. Arrow. Each one of them seems to have found Its own special niche, a sinecure Sword. Inkwell. Tombstone. Longbow. Watertap. Kite. Jackfruit. Brahmin. Duck. Maize. Their job is just to go on being themselves and their appointment is for life. Yajna. Chariot. Garlic. Ostrich. Hexagon. Rabbit. Deer. Lotus. Archer. No, you don't have to worry. There's going to be no trouble in this peaceable kingdom. The mother will not pound the baby with a pestle. The Brahmin will not fry the duck in garlic. That ship will not crash against the watermelon. If the ostrich won’t eat the child’s frock, The archer won’t shoot an arrow in Ganapati’s stomach. And as long as the ram resists the impulse of butting him from behind what possible reason could the Man-Touching-his-Toes have to smash the cup on the tombstone? see Rajiv Patke's fascinating review comparing Kolatkar's translation above with the version by Vinay Dharwadker (appearing in The Oxford Anthology of Modern Indian Poetry ed. Vinay Dharwadker and A.K. Ramanujan, 1994)

from Drunk and Other songs (III. Words for Music)

door to door blues p.278

it's only eleven were you asleep o well at least i didn't ring the wrong doorbell thank god i found your place i been here before but it's dark outside one can't see the name on the door i was wondering if you'd let me stay the night i haven't eaten all day i could do with a bite a slice of bread will do or maybe a sausage then i'll lie down in the balcony or here in the passage i won't be trouble i'm used to sleeping on the floor please don't bother i don't want a blanket don't want a pillow i'm completely broke i've nowhere else to go i can't sleep on the road the cops have told me so you won't have to ask me to join you for breakfast tomorrow i'll answer the door when the milkman comes and i will go p.278

Taxi song p.279

i been checking out on my friends and it looks like i've none they know i'm down on luck they know i'm on a drunk they know i'll come ask for money and so they hide or run up and down and round about from one end of town to the other you taken me to ten addresses from colaba to dadar you think i aint gonna pay you after all that trouble well that's where you are wrong 'cause i'm gonna pay you double so don't stop now taxi driver don't stop now and please don't shout i'm not gonna pay you now and aint gonna throw me out [...]

Translations

Tukaram: My body takes on

p.307 My body takes on a cadaverous aspect And I find my way To the burning-ghat. Desire, anger, love Weep unceasingly. Codes of conduct wail, Disconsolate. The dung cakes of Vairagya press Against my limbs. The apocalypse flares. Smashed, the earthen pot Spills embers at My feet. Mourners toll The sky like a bell. I disown my lineage, My name, my mien. I restore my body To whom it belongs. Now all is well and Effortlessly ash. The guru graced the lamp With a flame, says Tuka.

Tukaram: Narayan is insolvent

p. 312 Narayan is insolvent He has borrowed Right and left. Pay up, pay up, Clamour the creditors. He dare not stir In his own house. He hides Under the bed. Maya declare He isn't in. I don't make A lot of noise As the dept is old, Old as the world. See the note He signed, With the four Vedas As witnesses. Tuka the shopkeeper The said creditor... Vithal The said debtor...

Tukaram : It was a case (God rob God)

p. 316 It was a case Of God rob God. No cleaner job Was ever done. God left God Without a bean. God left no trace No trail no track. The thief was lying Low in His flat. When He moved He moved fast. Tuka says: Nobody was Nowhere. None was plundered And lost nothing.

Tukaram: You pawned

p.317 You pawned Your feet And got My faith. Love is The interest: I say Shell out. Your name Is my document -- And your funeral . Listen Says Tuka: You who make The eagle manifest-- My guru will be witness.

Tukaram : I it was

p. 318 I it was Begat me My knees Received me. My one desire granted. Of all desire I'm deserted. A new power Moves me Since that hour Killed me.

Tukaram : Tuka is stark raving mad p.321

Tuka is stark raving mad He talks too much His vocabulary: Ram Krishna Govind Hari Of any God save Pandurang Tuka is ignorant He expects revelation At any time, from any one Words on him are wasted He dances before God, naked Weary of men and manners With pleasure he rolls in gutters Ignoring instruction, all He ever says is 'Vithal, Vithal' O pundits, O learned ones Spit him out at once

The boatride p.329

the long hooked poles know the nooks and crannies find flaws in stonework or grappling with granite ignite a flutter of unexpected pigeons and the boat is jockeyed away from the landing after a pair of knees has shot up and streaked down the mast after the confusion of hands about the rigging an off-white miracle the sail spreads

because a sailor waved back to a boy another boy waves to another sailor in the clarity of air the gesture withers for want of correspondence and the hand that returns to him the hand his knee accepts as his own is the hand of an aged person a hand that must remain patient and give the boy it's a part of time to catch up frozen in a suit the foreman self-conscious beside his more self-conscious spouse finds illegible the palm that opens demandingly before him the mould of his hands broken about his right knee he reaches for a plastic wallet he pays the fares along the rim of the boat lightly the man rests his arm without brushing against his woman's shoulder gold and sunlight fight for the possession of her throat when she shifts in the wooden seat and the newly weds exchange smiles for small profit

show me a foreman he says to himself who knows his centreless grinding oilfired saltbath furnace better than i do and swears at the seagull who invents on the spur of the air what is clearly the whitest inflection known and what is clearly for the seagull over and above the wwaves a matter of course

the speedboat swerves off leaving behind a divergence of sea and the whole harbour all that floats must bear the briny brunt the sailboat hurl its hulk over burly rollers surmounted soon in leaps and bounds a gull hitched on hump the long trail toils on bringing to every craft a measure of imbalance a jolt for a dinghy a fillip to a schooner a swagger to a ketch and after the sea wall scabby and vicious with shells has scalped the surge after the backwash has reverted to the bulk of water all things that float resume a normal vacillation [...]

his wife has dismissed the waves like a queen a band of oiled acrobats in her shuttered eyes move in dark circles they move against her will winds like the fingers of an archaeologist move across her stony face and across the worn edict of a smile cut thereon her husband in chains is brought before her he clanks and grovels throw him to the wolves she says staring fixedly at a hair in his right nostril. a two-year-old renounces his mother's ear and begins to cascade down her person rejecting her tattooed arm denying her thighs undaunted by her knees and further down her shanks devolving he demands balloons and balloons from father to son are handed down closer to keel than all elders are and down there honoured among boots chappals and bare feet he goes into a huddle with the balloons coming to grips with one being persuasive with another and setting an example by punishing a third

two sisters that came last when the boat nearly started seated side by side athwart on a plank have not spoken hands in lap they have been looking past the boatman's profile splicing the wrinkles of his saline face and loose ends of the sea [...]

the boat courses around to sidle up against the landing the wall sweeps by magisterially superseding the music man an expanse of unswerving stone encrusted coarsely with shells admonishes our sight

awards have many uses p.343

awards have many uses they silence the critics convince the illiterates confirm the faith of the few who always believed in you ... awards are also like silver nails in the poet’s coffin they are a nice way of burying poets who seem to have been around for far too long instead of dying early as all good poets should on the other hand a poet is under no obligation to stop writing just because he is buried [...]

making love to a poem p.345

(from the Appendix) Translating a poem is like making love having an affair Making love to a poem with the body of another language you may meet a poem you like getting to know the poem carnally gaining carnal knowledge a consenting poem having made sure that the poem is above the age of consent varieties of the experience if the poem is ready / game / willing it may need as much skill, patience, delicacy to consummate the act Having got the poem into bed you may discover you're not up to it or that it's just not your day / or night it follows that translating your own poems is like making love to one of your own daughters it ought to be a cognizable offence taboo carry a stigma there ought to be a law against translating your own poems (unless the law against incest already covers it) [...]

blurb from back of book

Arun Kolatkar (1931-2004) was one of India’s greatest modern poets. He wrote prolifically, in both Marathi and English, publishing in magazines and anthologies from 1955, but did not bring out a book of poems until he was 44. His first book of poetry, Jejuri (1976), won him the Commonwealth Poetry Prize. His third Marathi publication, Bhijki Vahi, won a Sahitya Akademi Award in 2004. Both an epic poem, or sequence, celebrating life in the Indian city (and site of pilgrimage) of that name in the state of Maharashtra, Jejuri was later published in the US in the NYRB Classics series, with an introduction by Amit Chaudhuri, an edited version of which was published by The Guardian in 2006: see this link for Chaudhuri's account of 'the poet who deserves to be as well-known as Salman Rushdie'. Always hesitant about publishing his work, Kolatkar waited until 2004, when he knew he was dying from cancer, before bringing out two further books, Kala Ghoda Poems (a portrait of all life happening in Kala Ghoda, his favourite street) and Sarpa Satra. A posthumous selection, The Boatride and Other Poems (2008), edited by his friend, the poet and critic Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, contained his previous uncollected English poems as well as translations of his Marathi poems; among the book’s surprises were his translations of bhakti poetry, song lyrics, and a long love poem, the only one he wrote, cleverly disguised as light verse. Arun Kolatkar's Collected Poems in English, published by Bloodaxe Books in 2010, also edited by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, brought together work from the four volumes published in India by Ashok Shahane at Pras Prakashan. Jejuri offers a rich description of India while at the same time performing a complex act of devotion, discovering the divine trace in a degenerate world. Salman Rushdie called it ‘sprightly, clear-sighted, deeply felt…a modern classic’. For Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, it was ‘among the finest single poems written in India in the last forty years…it surprises by revealing the familiar, the hidden that is always before us’. Jeet Thayil attributed its popularity in India to ‘the Kolatkarean voice: unhurried, lit with whimsy, unpretentious even when making learned literary or mythological allusions. And whatever the poet’s eye alights on – particularly the odd, the misshapen, and the famished – receives the gift of close attention.’

A.K. Mehrotra: Arun Kolatkar: genius of modern Indian poetry (intro)

excerpts from full article at bloodaxeblogs All his life Kolatkar had an inexplicable dread of publishers’ contracts, refusing to sign them. This made his work difficult to come by, even in India. Jejuri was first published by a small co-operative, Clearing House, of which he was a part, and thereafter it was kept in print by his old friend, Ashok Shahane, who set up Pras Prakashan with the sole purpose of publishing Kolatkar’s first Marathi collection Arun Kolatkarchya Kavita. In the event, Shahane ended up as publisher of both Kolatkar’s English and Marathi books, which together come to ten titles to date, with more forthcoming, including a newly-discovered Marathi version of Jejuri, a book of interviews, and a novel in English. The small press, despite the obvious limitations, suited Kolatkar. He was, for one, in complete control of the way the book looked, from its format (he did not want his long lines to be broken), cover design, endpapers, and blurb to what went on the spine, which in the case of Kala Ghoda Poems and Sarpa Satra was precisely nothing, no title, no author’s name, no publisher’s logo. The four books that comprise the Collected Poems in English appear in the order in which they were published. Though The Boatride and Other Poems contains some of his earliest poems, it seemed proper to open a collected volume with Jejuri, which was Kolatkar’s first book and the work he is most associated with. There comes a time in the life – or afterlife – of every cult figure when, escaping from the small group of readers that had kept the flame burning, mainly through word of mouth, he begins to belong to a larger world. With the publication of Collected Poems in English, Kolatkar’s moment has perhaps come.

Arvind Krishna Mehrotra: Death of a poet

(from intro to Boatride and other poems, 2008)

Arun Kolatkar, who is widely regarded as one of the great Indian poets of the

last century, was born in Kolhapur, Maharashtra in 1931. His father was an

educationist, and after a stint as the principal of a local school he taught

at a teacher’s training college in the same city. ‘He liked nothing better in

life than to meet a truly unteachable object,’ Kolatkar once said about

him. In an unpublished autobiographical essay which he read at the Festival

of India in Stockholm in 1987, Kolatkar describes the house in Kolhapur where

he spent his first eighteen years:

I grew up in a house with nine rooms that were arranged, well almost,

like a house of cards. Five in a row on the ground, topped by three on

the first, and one on the second floor.

The place wasn’t quite as cheerful as playing cards, though. Or as

colourful. All the rooms had mudfloors which had to be plastered with

cowdung every week to keep them in good repair. All the walls were

painted, or rather distempered, in some indeterminate colour which I

can only describe as a lighter shade of sulphurous yellow.

It was in one of these rooms – his father’s study on the first floor – that

Kolatkar found ‘a hidden treasure’. It consisted of

three or four packets of glossy black and white picture postcards

showing the monuments and architectural marvels of Greece, as well as

sculptures from the various museums of Italy and France.

As I sat in my father’s chair, examining the contents of his drawers,

it was inevitable that I should’ve been introduced to the finest

achievements of Baroque and Renaissance art, the works of people like

Bernini and Michaelangelo, and I spent long hours spellbound by their

art.

But at the same time I must make a confession. The European girls

disappointed me. They have beautiful faces, great figures, and they

showed it all. But there was nothing to see. I looked blankly at their

smooth, creaseless, and apparently scratch-resistant crotches, sighed,

and moved on to the next picture.

The boys, too. They let it al hang out, but were hardly what you might

call well-hung. David, for example. Was it David? Great muscles, great

body, but his penis was like a tiny little mouse. Move on. Next

picture.

After matriculating in 1947, Kolatkar attended art school in Kolhapur, and,

in 1949, joined the Sir J.J. School of Art in Bombay. He abandoned it two

years later, midway through the course, but went back in 1957, when he

completed the assignments and, finally, took the diploma in painting. The same

year he joined Ajanta Advertising as visualiser, and quickly established

himself in the profession which, in 1989, inducted him into the hall of fame

for lifetime achievement.

Kolatkar also led another life, and took great care to keep the two lives

separate. His poet friends were scarcely aware of the advertising legend in

their midst, for he never spoke to them about his prize-winning ad campaigns

or the agencies he did them for. His first poems started appearing in English

and Marathi magazines in the early 1950s and he continued to write in both

languages for the next fifty years, creating two independent and equally

significant bodies of work. Occasionally he made jottings, in which he

wondered about the strange bilingual creature he was:

I have a pen in my possession

which writes in 2 languages

and draws in one

__

My pencil is sharpened at both ends

I use one end to write in Marathi

the other in English

__

what I write with one end

comes out as English

what I write with the other

comes out as Marathi

His first book in English, Jejuri, a sequence of thirty-one poems based on a

visit to a temple town of the same name near Pune, appeared in 1976 to

instant acclaim, winning the Commonwealth Poetry Prize and establishing his

international reputation. The main attraction of Jejuri is the Khandoba

temple, a folk god popular with the nomadic and pastoral communities of

Maharashtra and north Karnataka. Only incidentally, though, is Jejuri about a

temple town or matters of faith. At its heart, and at the heart of all of

Kolatkar’s work, lies a moral vision, whose basis is the things of this

world, precisely, rapturously observed. So, a common doorstep is revealed to

be a pillar on its side, ‘Yes. / That’s what it is’; the eight-arm-goddess,

once you begin to count, has eighteen arms; and the rundown Maruti temple,

where nobody comes to worship but is home to a mongrel bitch and her puppies,

is, for that reason, ‘nothing less than the house of god.’ The matter of fact

tone, bemused, seemingly offhand, is easy to get wrong, and Kolatkar’s

Marathi critics got it badly wrong, finding it to be cold, flippant, at best

sceptical. They were forgetting, of course, that the clarity of Kolatkar’s

observations would not be possible without abundant sympathy for the person

or animal (or even inanimate object) being observed; forgetting, too, that

without abundant sympathy for what was being observed, the poems would not be

the acts of attention they are.

Far from mocking what he sees, Kolatkar is divinely struck by everything

before him, as much by the faith of the pilgrims who come to worship at

Jejuri’s shrines as by the shrines themselves, one of which happens to be not

shrine at all:

The door was open.

Manohar thought

It was one more temple.

He looked inside.

Wondering

which god he was going to find.

He quickly turned away

when a wide eyed calf

looked back at him.

It isn’t another temple,

he said,

it’s just a cowshed.

(‘Manohar’)

The award of the prize inevitably led to interviews, which, except for the

interview Eunice de Souza did later, are the only ones Kolatkar ever gave. In

one interview, to a Marathi little magazine that brought out a special issue

on him, Kolatkar was asked about his favourite poets and writers. ‘You want

me to give you their names?’ he replied, and then proceeded to enumerate

them:

Whitman, Mardhekar, Manmohan, Eliot, Pound, Auden, Hart Crane, Dylan

Thomas, Kafka, Baudelaire, Heine, Catullus, Villon, Dnyaneshwar,

Namdev, Janabai, Eknath, Tukaram, Wang Wei, Tu Fu, Han Shan, Ram

Joshi, Honaji, Mandelstam, Dostoevsky, Gogol, Isaac Bashevis Singer,

Babel, Apollinaire, Breton, Brecht, Neruda, Ginsberg, Barth, Duras,

Joseph Heller, Günter Grass, Norman Mailer, Henry Miller, Nabokov,

Namdev Dhasal, Patthe Bapurav, Rabelais, Apuleius, Rex Stout, Agatha

Christie, Robert Shakley, Harlan Ellison, Bhalchandra Nemade,

Dürrenmatt, Arp, Cummings, Lewis Carroll, John Lennon, Bob Dylan,

Sylvia Plath, Ted Hughes, Godse Bhatji, Morgenstern, Chakradhar,

Gerard Manley Hopkins, Balwantbuva, Kierkegaard, Lenny Bruce,

Bahinabai Chaudhari, Kabir, Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, Leadbelly,

Howling Wolf, John Lee Hooker, Leiber and Stoller, Larry Williams,

Lightning Hopkins, Andrzej Wajda, Kurosawa, Eisenstein, Truffaut,

Woody Guthrie, Laurel and Hardy.

‘The astonishing admixture (off the top of his head),’ the American scholar

of Marathi Philip Engblom has said of the list, ‘not only of nationalities

but of artistic genres (symboliste poetry to art film to Mississippi and

Chicago Blues to Marathi sants) speaks volumes about the environment in which

Kolatkar produced his own poetry’.

And not just Kolatkar. In the introduction to his Anthology of Marathi

Poetry: 1945-1965 (1967), in which some of Kolatkar’s best-known early poems

like ‘Woman’ and ‘Irani Restaurant Bombay’ first appeared, Dilip Chitre writes

about ‘the paperback revolution’ which

unleashed a tremendous variety of…influences [that] ranged from

classical Greek and Chinese to contemporary French, German, Spanish,

Russian and Italian. The intellectual proletariat that was the

product of the rise in literacy was exposed to these diverse

influences. A pan-literary context was created.

[…]

Cross-pollination bears strange fruits. [Bal Sitaram] Mardhekar wrote

books on literary criticism and aesthetic theory which make

references to contacts with various European works of art and

literature… During his formative years as a writer, he was deeply

influenced by Joyce and Eliot, and these continued to be critical

influences in his critical writing throughout his career, until his

untimely death in 1956.

After the success of Jejuri, except for the odd poem in a magazine, Kolatkar

did not publish anything. To friends who visited him, he would sometimes read

from whatever he was working on at the time, but there were to be no further

volumes. Then in July 2004 he brought out Kala Ghoda Poems and Sarpa

Satra. At a function held at the National Centre for the Performing Arts’

Little Theatre in Bombay, five poets read from the two books. Kolatkar,

wearing a black t-shirt and brown corduroy trousers, sat in the audience. He

was by then terminally ill with stomach cancer and did not have long to live.

To his readers it must have seemed at the time, as it did to me, that the

publication of these long awaited new books by Kolatkar, twenty-eight years

after he published Jejuri, completed his English oeuvre. There were some

scattered uncollected poems of course, most notably the long poem ‘the

boatride’, but they had appeared in magazines and anthologies before and in

any case were not enough to make another full-length collection. Which is why

when Ashok Shahane, Kolatkar’s publisher, first brought up the idea of The

Boatride and Other Poems and asked me to draw up a list of things to include

in it I was sceptical. In the event, the list, based on what was available on

my shelves, did not look as meagre as I had feared. It had thirty-two poems

divided into three sections: ‘Poems in English’, which had poems written

originally in English; ‘Poems in Marathi’, which had poems written originally

in Marathi but which he translated into English; and ‘Translations’, which

had translations of Marathi bhakti poets, mostly of Tukaram. The first poem in

the first section was ‘The Renunciation of the Dog’, written in 1953. A poem

titled ‘A Prostitute on a Pilgrimage to Pandharpur Visits the Photographer’s

Tent During the Annual Ashadhi Fair’, from his Marathi book Chirimiri, was

from the 1980s.

The Boatride and Other Poems, I remember thinking to myself, though small

in terms of the number of pages, would be the only book to represent all the

decades of Kolatkar’s writing life barring the last and the only one to have,

between the same covers, his English and Marathi poems. Kolatkar approved of

the selection when we discussed it over the phone and made one suggestion,

which was to put ‘the boatride’ not with the ‘Poems in English’, as I had

done, but at the end of the book, in a section of its own. The reason for

this, though he did not say it in so many words, was that in its overall

structure, which is that of a trip or journey described from the moment of

setting out to the moment of return, and in its observer’s tone, ‘the

boatride’, though written ten years earlier, prefigures Jejuri, which was his

next sequence.

A week or two after this conversation when next I spoke with Kolatkar he

surprised me by saying that I should edit The Boatride. Since the book’s

contents had already been decided and there were no further poems to add, or

at least none that I was aware of, my role at the time, as editor, seemed

limited to ensuring that we had a good copy-text. But even this, I realised,

would not be easy.

My last phone conversation with Kolatkar was early in the third week of

September. By then he had stopped going to Café Military, an Irani restaurant

in Meadows Street, where over cups of tea he routinely met with a close

circle of friends on Thursday afternoons, as he had earlier met them, for

more than three decades, at Wayside Inn in Kala Ghoda before the place shut

down in 2002. When his condition deteriorated, his family shifted him to

Pune, to the house of his younger brother, who was a doctor. He had already

been in Pune ten days when I made the phone call and found that he was too

weak to speak. When I persisted, a little excitedly I’m afraid, in asking him

about ‘The Turnaround’, he said it was ‘an inner journey’ and mumbled

something about a ‘personal crisis’. He said he’d explain everything if I

came to Pune. I took the next train.

I reached Pune late in the evening of the 21st and made my way to his

brother’s house in Bibwewadi. The house was in a side street, a duplex in a

row of identical houses, each having a modest front yard with a motor scooter

or car, often both, parked in it. Kolatkar was in an upstairs room and seemed

to be asleep. The brother who was a doctor was still at his clinic, but his

two other brothers, Sudhir and Makarand, were there, as was his wife

Soonoo. ‘His mouth is constantly parched,’ Sudhir said, ‘and that’s affected

his speech. He also cannot take in any food. But he feels a little better in

the mornings. Maybe you should come back tomorrow and put your questions to

him.’ Looking at Kolatkar, there wasn’t much hope of getting answers.

Editing 'The Boatride'

‘The Renunciation of the Dog’ is one of fourteen English poems, collectively called ‘journey poems’, written during 1953-54. Though they all came out of the same experience, the walking trip through western Maharashtra, there is nothing in the poems that identifies them with a particular landscape. It is as though, in 1953, Kolatkar had staked off his subject but not located the poetic resources to express it in. Never a man in a hurry, he was prepared to wait. The wait ended in 1967 when he wrote, in Marathi, ‘Mumbaina bhikes lavla’. Its English translation, ‘The Turnaround’, he did in 1987, to read at the Stockholm festival. Kolatkar showed the ‘journey poems’ to his friends, one of whom, Dnyaneshwar Nadkarni, who later became a well-known art critic and writer on Marathi theatre, passed them on to Nissim Ezekiel. As editor of Quest, a new magazine funded by the Congress for Cultural Freedom, Ezekiel was open to submissions. He also had an eye for talent and this time, in Kolatkar, he spotted a big one. He decided to carry ‘The Renunciation of the Dog’ in the magazine’s inaugural issue, which appeared in August 1955. It was Kolatkar’s first published poem in English. Around then, he and Ezekiel also met for the first time. For someone who was to spend his next fifty years in advertising, Kolatkar’s meeting with Ezekiel, fittingly enough, took place in the offices of Shilpi, where Ezekiel had a job as copywriter. A line below ‘The Hag’ and ‘Irani Restaurant Bombay’ in Chitre’s Anthology of Marathi Poetry says ‘English version by the poet’, suggesting that the two poems are translations. I knew from previous conversations with Kolatkar that he wrote them both in English and Marathi and considered them to be as much English poems as Marathi ones. Now, in Pune, as Soonoo dabbed his lips with wet cotton wool to keep them moist, he spoke about them again. The Marathi and English versions, he said, were ‘very closely related’; ‘they can bear close comparison’. He also said he wrote them ‘side by side’. Of ‘The Hag’ and ‘Therdi’ (its Marathi title) he said he would write one line in Marathi and a corresponding line in English, or the other way round. ‘They run each other pretty close.’ He also commented on the rhyme scheme: ‘There is no discrepancy.’ Chitre, whom I’d rung up on reaching Pune, came with his wife Viju to see Kolatkar. He had with him an office file and a spiral bound book consisting of photocopies made on card paper. He asked me to look at them. He had recently finished a short film on Kolatkar for the Sahitya Akademi, and the office file and the spiral bound book, both of which Darshan had given him, were part of the archival material he’d collected. The poems in the file consisted mostly of juvenilia, and some, with their references to ‘a begging bowl’ and ‘the changing landscape’, looked like they belonged with the ‘journey poems’, which, as I found out later, they indeed did: Destined to become a begging bowl We let rise our clay And holding it in our hand Wordlessly and worldlessly To be filled and fulfilled We wandered In the wilderness of our heart and We retreated from ourselves To become the changing landscape And the mutable topography That accompanied us And whispered in our ears I quickly went through the poems and read them out to Kolatkar. If I liked something I asked him if I could put it in The Boatride, and if he said yes I’d put a tick against it. The ones I ticked were ‘Of an origin moot as cancer’s’, ‘Dual’, ‘In a godforsaken hotel’, and ‘my son is dead’. The poems were typewritten and some had obvious typos. A line in ‘Dual’ read ‘the two might declare harch thorns and live’. ‘Harch’? I asked Kolatkar. ‘Harsh.’ In the list I had sent him, the one he had approved of, the ‘Poems in English’ section had eight poems. Now it had twelve. Clearly, The Boatride was going to be a bigger book than I had anticipated; I also began to see why Kolatkar wanted it to have an editor. In 1966, Kolatkar joined an advertising studio, Design Unit, in which he was one of the partners. It did several successful campaigns, including one for Liberty shirts, which won the Communication Artists Guild award for the best campaign of the year. The Liberty factory had recently been gutted in a fire and the copy said ‘Burnt but not extinguished’; Kolatkar did the visuals, one of which showed a shirt, with flames leaping from it. The studio was in existence for three years and everything in the spiral bound book was from this period of Kolatkar’s life. In fact, it was his Design Unit engagement diary, whose pages Darshan had rearranged and interspersed with poems, drawings and jottings. Flipping through it was like peeking into an artist’s lumber-room, crammed with bric-à-brac. It revealed more about Kolatkar’s public life as successful advertising professional and private life as poet than a chapter in a biography would have. The first page had a drawing of a gladiolus, the curved handle of an umbrella sticking through the leaves. Other drawings showed an umbrella hanging from a sickle moon; from an antelope’s horns; from a man’s wrist; stuck in a vase; safely tucked behind a man’s ear like the stub of a pencil; placed with a cup and saucer, like a spoon, to stir the tea with. The text accompanying the drawings was always the same, ‘Keep it’. Between the drawings were jottings, scribbles, messages (‘Darshan Kolatkar 40 Daulat Send me my green shirt’), expenditure figures (‘Liquor 37.75’), memos to himself (‘plan & save cost; meetings fortnightly; how to inspire/educate artists’), names and telephone numbers of clients, appointments to keep or cancel, seemingly useless scraps of paper preserved only because those who were close to him were farsighted and valued every scrap he put pen to. One page had written in it ‘Ring Farooki’; ‘Ring Pfizer’; ‘Ring Mrs Chat. cancel 3.30 Tues. appt.’; ‘?Bandbox?’; ‘7.30 Kanti Shah’; and somewhere in the middle was also the drawing of a man with a V-shaped face and arrows for arms and legs, the right arrow-leg pointing to ‘12.00 Jamshed’. Against a drawing of a cut-out-like figure he had written, ‘Imagine he is the client you hate most and stick a pin anywhere.’ And above it, ‘Just had a frustrated meeting with a frustrated client. This fellow goes on and on. I do not like long telephonic conversations. The client is a Marwari, you know.’ In an invoice to one Mrs Mukati dated ‘9/9/67’, he had jokily scribbled ‘10,000’ under ‘Quantity’ and ‘Good mornings’ under ‘Please receive the following in good order and condition’. The scribble on the invoice, the drawings and the poems, whether early or late, are part of the same vision. Enchanted by the ordinary, Kolatkar made the ordinary enchanting. Which is why, however familiar one may be with his work, it’s always as though one is encountering it for the first time. ‘[T]he dirtier the better’ he says of the ‘unwashed child’ in a poem in Kala Ghoda, ‘The Ogress’, and the same might be said about the subjects he was drawn to: the humbler the better. When the ogress, as Kolatkar calls her, gives the ‘tough customer on her hands’, ‘a furious, foaming boy’, a good scrub, she has a ‘wispy half-smile’ on her face and ‘a wicked gleam’ in her eye. One imagines Kolatkar’s face bore a similar expression when he mischievously transformed the humble invoice into a cheery greeting. What can be more uninspiring, more ordinary, or, sometimes, more enchanting, than the tall stories men tell each other when they meet in a restaurant over a cup of tea? In ‘Three Cups of Tea’ Kolatkar reproduces verbatim, in ‘street Hindi’ (and translates into American English), three such stories. He wrote the poem in 1960, at the beginning of the revolutionary decade that we associate more with Andy Warhol’s 1964 Brillo Box exhibition and the music of John Cage than with Kolatkar’s poem; more with New York than Bombay. Yet the impulse behind their works is the same, to erase the boundaries between art and ordinary speech, or art and cardboard boxes, or art and fart, whose sound Cage incorporated into his music. The impulse has its origin in Marcel Duchamp’s famous ‘ready-mades’, the snow shovels, bicycle wheels, bottle racks and urinals he picked off the peg. It was art by invoice.

Kolatkar's influences

when he moved house from Bakhtavar in Colaba, to a much smaller one-room apartment in Prabhadevi, Dadar, he also sold off his substantial collection of music and science fiction books. Kolatkar may not have had space for books, but he continued to buy them as before, on a scale that would match the acquisitions of a small city library. (He purchased newspapers on the same scale too; five morning and three evening papers every day.) He bought books, read them, and passed them on to his friends. This is how I acquired my copy of Marquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera, which he had bought in hardback soon as it became available at Strand Book Stall. It was only a matter of time before books reappeared in his apartment, covering a wall from end to end. Scanning the titles, I found no poetry or fiction; instead, history. When, in her interview with him, Eunice de Souza remarked on the books on Bosnia on his shelves, Kolatkar dwelt at length on his reading habits: I want to reclaim everything I consider my tradition. I am particularly interested in history of all kinds, the beginning of man, archaeology, histories of everything from religion to objects, bread-making, paper, clothes, people, the evolution of man’s knowledge of things, ideas about the world or his own body. The history of man’s trying to make sense of the universe and his place in it may take me to Sumerian writing. It’s a browser’s approach, not a scholarly one; it’s one big supermarket situation. I read across disciplines and don’t necessarily read a book from beginning to end. I jump back and forth from one subject to another. I find reading documents as interesting as reading poetry. I am interested in the nature of history, which I find ambiguous. What is history? While reading it one doesn’t know. It’s a floating situation, a nagging quest. It’s difficult to arrive at any certainties. What you get are versions of history, with nothing final about them. Some parts are better lit than others, or the light may change, or one may see the object differently. I also like looking at legal, medical, and non-sacred texts – schoolboys’ texts from Egypt, a list of household objects in Oxyrhincus, a list of books in the collection of a Peshwa wife, correspondence about obtaining a pair of spectacles, deeds of sale, marriage and divorce contracts. One dimension of my interest in all this is literary, for example, in the Bible as literature. The Song of Solomon goes back to Egypt and Assyria. I like following these trails. Like all autodidacts, Kolatkar’s dream was to know (‘to reclaim’) everything, to hold all knowledge, like a shining sphere, in the palm of the hand. Nor did he give up reading fiction altogether. One winter I was in Bombay he was reading W.G. Sebald’s Austerlitz. He read widely, and if a question interested him, he would track down everything there was on it. When he was contemplating a poem on Héloïse for Bhijki Vahi (2003), each of whose twenty-five poems is centred around a sorrowing woman – from Isis, Cassandra and the Virgin Mary to Nadezhda Mandelstam, Susan Sontag, and his own sister, Rajani, who lost her only son, a cadet pilot in the Indian Air Force, in an air crash – he collected a shelf-full of books on the subject. Eventually he abandoned the idea of writing on Héloïse, saying to me that he had not been able to find a way into the story, by which he meant a new perspective on it that would make it different from a retelling. He faced a similar problem with Hypatia of Alexandria, which he solved by making St Cyril, who is thought to have had a hand in her murder, the poem’s speaker. [...]

Sarpa Satra

Based in the frame story of the Mahabharata, Sarpa Satra is also a contemporary tale of revenge and retribution, mass murder and genocide, and one person’s attempt to break the cycle. In the story, the divine hero Arjuna decides, ‘Just for kicks, maybe’, to burn down the Khandava forest. In a passage of great lyrical beauty, Kolatkar describes the conflagration in which everything gets destroyed, ‘elephants, gazelles, antelopes’ and people as well. Simple folk, children of the forest who had lived there happily for generations, since time began. They’ve gone without a trace. With their language that sounded like the burbling of a brook, their songs that sounded like the twitterings of birds, and the secrets of their shamans who could cure any sickness by casting spells with their special flutes made from the hollow wingbones of red-crested cranes. Among those who die in the ‘holocaust’ is a snake-woman, to avenge whose loss her husband, Takshaka, kills Arjuna’s grandson, Parikshit. Parikshit’s son, Janamejaya, then holds the snake sacrifice, the Sarpa Satra, to rid the world of snakes: ‘My vengeance will be swift and terrible. / I will not rest / until I’ve exterminated them all.’ Though the mass killing of snakes symbolically represents the many genocides of the last century, Kolatkar, by taking a story from an ancient epic, brings the whole of human history under the scrutiny of his moral vision. In the Mahabharata, Aasitka, whose mother is herself a snake-woman and Takshaka’s sister, is able to stop the sacrifice midway, but Kolatkar’s poem offers no such consolation: When these things come to an end, people find other subjects to talk about than just the latest episode of the Mahabharata and the daily statistics of death; rediscover simpler pleasures – fly kites, collect wild flowers, make love. Life seems to return to normal. But do not be deceived. Though, sooner or later, these celebrations of hatred too come to an end like everything else, the fire – the fire lit for the purpose – can never be put out. In July 2004, as we were on our way by taxi from Prabhadevi to Café Military, Kolatkar, looking out of the taxi window and then at me, remarked on his English and Marathi oeuvres. With the exception of Sarpa Satra, he said, his stance in ‘the boatride’, Jejuri and Kala Ghoda Poems had been that of an observer; he was on the outside looking in. He wondered whether he’d have gone on writing the same way if he’d lived for another ten years. The Marathi books, on the other hand, were all quite different, he said, and there was no obvious thread connecting Arun Kolatkarchya Kavita, Chirimiri and Bhijki Vahi. But there’s something else, too, that links ‘the boatride’, Jejuri and Kala Ghoda Poems. Each of them is arranged in the cyclic shape of the Ouroboros, their last lines suggestingly leading to their opening ones. Jejuri begins with ‘daybreak’ and ends with the ‘setting sun / large as a wheel’. Similarly, Kala Ghoda Poems begins with a ‘traffic island’ ‘deserted early in the morning’ and ends with the ‘silence of the night’, the ‘traffic lights’ ‘like ill-starred lovers / fated never to meet’. In ‘the boatride’, the boat jockeys ‘away / from the landing’ and returns to the same spot when the ride is over. It will fill up with tourists and set off again, just as the state transport bus in Jejuri, at the end of the ‘bumpy ride’, will deliver a fresh batch of ‘live, ready to eat’ pilgrims to the temple priest. His Bombay friends had meanwhile been arriving through the morning to see Kolatkar. It was a Thursday, and the crowd around his bed – Adil Jussawalla, Ashok Shahane, Raghoo Dandavate, Kiran Nagarkar, Ratnakar Sohoni – was a little like the Thursday afternoon crowd around his table at Wayside Inn. Also in the room were Dilip and Viju Chitre. Sohoni was Kolatkar’s Prabhadevi neighbour and had known him since his Design Unit days.

"Drunk and Other songs"

(from poems Kolatkar had set aside for showing AKM)

The first folder I pulled out from it was marked ‘Drunk & other

songs. Late sixties, early seventies’. This was the period when Kolatkar’s

interest in blues, jazz and rock ’n’ roll took a new turn. He learnt musical

notation and took lessons in the guitar and, from Arjun Shejwal, the

pakhawaj, and started to write songs, recording, in 1973, a demo consisting

of ‘Poor Man’, ‘Nobody’, ‘Joe and Bongo Bongo’ and ‘Radio Message from a

Quake Hit Town’. Three of these are “found” songs, further examples of

Kolatkar’s transformations of the commonplace. ‘Joe and Bongo Bongo’ and

‘Radio Message from a Quake Hit Town’ were based on newspaper reports and

‘Poor Man’ took its inspiration from the piece of paper that beggars thrust

before passengers waiting in bus queues and at railway stations. It gives the

beggar’s life story and ends with an appeal for money. ‘Poor Man’ has an

ananda-lahari in the background, an instrument that is popular with both

beggars and mendicants, particularly the Baul singers of Bengal. While its

plangent music is truthful to the origin of the song, the beggar’s appeal, it

also provides a nice contrast to the outrageous lyrics in which the ‘poor man

from a poor land’ is an aspiring rock star, who is singing not for his next

meal but because he wants ‘a villa in the south of france’ and ‘a gold disk

on [his] wall’.

In October 1973, one of Kolatkar’s friends, Avinash Gupte, who was travelling

to London and New York, tried to interest agents and music companies there in

the demo but nothing came of the effort. Kolatkar’s shot at the ‘gold disk’

had ended in disappointment and he abandoned all future musical plans. He

filed away the ‘Drunk & other songs’, never to return to them again. Instead,

in November-December of that year, he sat down and wrote Jejuri, completing

it in a few weeks.

One by one, I read out the ‘Drunk & other songs’, many of which I was seeing

for the first time. I wanted to know which ones to include in The Boatride

and, in case there was more than one version, which version to use. I read

them in the order I found them.

tape me drunk

my sister

my chipmunk

spittle spittle spittle

gather my spittle

but never in a hospital

don’t tie me down

promise me pet

don’t tie me down

to a hospital bed

my salvation i believe

is in a basket of broken eggs

yolk on my sleeve

and vomit on my legs

o world

what is my worth

o streets

where is my shirt

begone my psychiatrist

boo

but before you do

lend me your trousers

because in mine i’ve pissed

‘That sounds honourable enough,’ Kolatkar joked after I’d finished reading

it. I read out the next one:

hi constable tell me what’s your collar size

same as mine i bet this shirt will fit you right

the shirt is yours feel it don’t you like the fall

all you got to do to get it is make one phone call…

‘Drunk,’ he said, by way of categorising the song. During his drinking days,

Kolatkar had had his run-ins with the police, being picked up for disorderly

behaviour on at least one occasion. Years later, he recalled the jail

experience in Kala Ghoda Poems:

Nearer home, in Bombay itself,

he miserable bunch

of drunks, delinquents, smalltime crooks

and the usual suspects

have already been served their morning kanji

in Byculla jail.

They’ve been herded together now

and subjected

to an hour of force-fed education.

(‘Breakfast Time at Kala Ghoda’)

But the poems I was reading to him from the folder were nearer in time to the

experience they described:

nothing’s wrong with me man

i’m ok

it’s just that i haven’t had a drink all day

let me finish my first glass of beer

and this shakiness will disappear

you’ll have to light my cigarette i can’t strike a match

but see the difference once the first drink’s down the hatch

‘Straight drunk,’ came his response, quickly. To other songs, after hearing

the first line, he said I could decide later whether to include them or not

and to those towards the end he said ‘Skip’. Barring two, I have included all

the songs in the folder. They appear in a separate section, ‘Words for

Music’.

Other reviews

from review of Boatride and other poems by Sampurna Chattarji

http://sampurnachattarji.wordpress.com/book-reviews/ Picking up Arun Kolatkar’s The Boatride & other poems feels a lot like revisiting an old friend in anticipation of much joy and newness. Just how much is what’s revelatory about the collection, published five years after Kolatkar’s death in 2004, edited and with a superb introduction by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra. Titled ‘Death of a Poet’, the introduction not only chronicles the last few conversations Mehrotra had with Kolatkar, but also gives us a wonderfully lucid overview of the poet, the man, the mischief-maker, the flaneur/loafer, the fan of American music, of Big Mama Thornton and Elvis, the autodidact and the prodigious reader. Erudite and engaging, the introduction sets the perfect tone for the book, which is divided into five sections—‘Poems in English 1953-1967’, ‘Poems in Marathi’, ‘Words for Music’, ‘Translations’ and the final section, which contains the long poem ‘the boatride’. Right away, the second poem in the book, ‘Of an origin moot as cancer’s’, demonstrates something many poets (especially young poets) forget—namely, the way in which the simplest of words can create the most complex of effects. Wordplay is something Kolatkar revelled in, and the next poem ‘Dual’—with the deliciously apt echo of ‘duel’ ghosting below its surface—is no exception. As “A man and a woman in a radical cage/ Grope and get bruised in an animal light”, the word ‘light’ itself becomes a weapon in the hands of the pitiless observer, the amused spectator. The “unlearnt skin” of the couple, “dazzled/ in the narcotic light, is blunt and smooth/ like the fat palm of an infant cactus.” The short poem ends: The two might declare harsh thorns and live as insensate as a cactus, piteously bristled and opposing the light. ... Kolatkar’s ability to be brutal and beautiful in the same breath is brilliantly apparent in poems like ‘One seldom sees a woman’ which ends: for a moment the saliva of the horse glittered on your finger like a wedding ring then the wind dropped see also: review of boatride, by Akhila Ramnarayan [in http://www.hindu.com/fline/fl2617/stories/20090828261707900.htm|The Hindu]

amitabha mukerjee (mukerjee [at-symbol] gmail) 2012 Nov 25