Visual intelligence: how we create what we see

Donald D. Hoffman

Hoffman, Donald D.;

Visual intelligence: how we create what we see

W. W. Norton & Company, 2000, 294 pages [gbook]

ISBN 0393046699 / 0393319679

topics: | cognitive | psychology | perception | optical-illusion | learning

While we measure people's intelligence by their differing abilities in solving intricate puzzles or doing algebra, we give little thought to our ability to interpret common everyday scenes in terms of their 3D structures. Yet, mathematically, any 2D image can be constructed from an infinite number of 3D scenes. Yet, our visual intelligence almost always provides the valid intepretation for what we see. Computationally, this opens up a large question - how is this possible? This is the question addressed elegantly by Hoffman (cog sci professor at UC Irvine) in this fascinating book. We take visual intelligence to be a given, because most of us effortlessly apply the right "biases" to construct the correct reality - as Hoffman says, we are each of us, a "creative genius", and we have only to open our eyes to see that. The interpretations we give to what impinges on our retina is arrived at by a complex processes, that we don't quite understand. Some of these are programmed into our genes (phylogeny), and some we learn based on what we see during our lifetime (ontogeny). Hoffman manages to hold interest while exploring the process by whith the brain constructs its interpretations of the world.

Extracts: Preface

After his stroke, Mr. P still had outstanding memory and intelligence. He could still read and talk, and mixed well with the other patients on his ward. His vision was in most respects normal---with one notable exception: He couldn't recognize the faces of people or animals. As he put it himself, "I can see the eyes, nose, and mouth quite clearly, but they just don't add up. They all seem chalked in, like on a blackboard ... I have to tell by the clothes or by the voice whether it is a man or a woman ...The hair may help a lot, or if there is a mustache ... ." Even his own face, seen in a mirror, looked to him strange and unfamiliar. Mr. P had lost a critical aspect of his visual intelligence. ... We have long known about IQ and rational intelligence. ... but are largely ignorant that there is even such a thing as visual intelligence---that is, until it is severely impaired, as in the case of Mr. P, by a stroke or other insult to visual cortex. The culprit in our ignorance is visual intelligence itself. Vision is normally so swift and sure, so dependable and informative, and apparently so effortless that we naturally assume that it is, indeed, effortless. But the swift ease of vision, like the graceful ease of an Olympic ice skater, is deceptive. Behind the graceful ease of the skater are years of rigorous training, and behind the swift ease of vision is an intelligence so great that it occupies nearly half of the brain's cortex. Our visual intelligence richly interacts with, and in many cases precedes and drives, our rational and emotional intelligence. To understand visual intelligence is to understand, in large part, who we are. As a culture we vote with our time and wallets and, in the case of entertainment, our vote is clear. Just as we enjoy rich literature that stimulates our rational intelligence, or a moving story that engages our emotional intelligence, so we also seek out and enjoy new media that challenge our visual intelligence.

Ch1 : Creative genius for vision

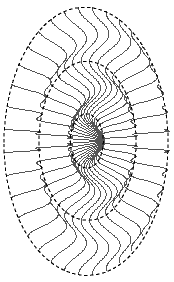

You are a creative genius... in a fraction of a second your visual intelligence can create the strut and colours of a peacock, or the fireworks of an ocean sunset... in repertoire and speed you far surpass the greatest of painters. But perhaps because you are unaware of it, you flatly disbelieve your inner talent. Yet you are constantly constructing images.It is impossible to see this set of lines as a flat drawing. Is this because of something we have learned, or is it programmed in our genes (phylogenetic)? Even bees apparently see it as 3D (p. 7)

If we rotate the picture upside-down, the hills and valleys are interchanged. A possible explanation for this bias may be that we expect to be looking at a scene from above.

The flip (between hills and valleys) appears to occur somewhere past the 90 degree mark. Like most such flips, it depends on which direction one starts from.

A square is clearly manifested among these lines. The central region appears brighter than the surround, though rationally, we also realize they must be the same luminosity. The eye (mind behind it) keeps fooling us. http://www.cogsci.uci.edu/personnel/hoffman/vonSchiller.html Vision, unlike language, is a genius we share with many other animals. [though animals vary widely]. Goldfish have colour vision, with four colour receptors, compared to our three; they also have color constancy - they can continue to find, say, green objects despite changes color of the ambient light. Honeybees have color constancy and can perceive the subjective magic square. They can also navigate using the sun as a compass, even if it's hidden behind a cloud; they find it via the polarization of UV rays from the blue patches in the sky. The fly uses visual motion to compute, in real time, how and when to land on a surface and how to alter its trajectory to intercept another fly. 7 Day-old chicks discriminate spheres from pyramics, and peck preferentially at the spherese (seeds are more likely to be spherical). The praying mantis uses binocular vision to depth-locate a fly and when the fly is at just the right distance, flicks out a foreleg to catch the fly in its tarsal-tibial joint. The mantis shrimp has ten colour receptors, can find the range to a prey with just a single eye, and accurately stuns its prey with a quick strike of its raptorial appendage. Macaque monkeys see "structure from motion" - with just one eye they can construct the 3D shape of a moving object. Niko Tinbergen showed that for blackbird nestlings, "Mom" (or parent) can be as simple as two adjacent disks (and they will gape at the image). One disk must have a diameter about thrice the other. The absolute size of the disks matters little, but if the ratio deviates much, or if there are extra disks, they are not "Mom". 8 Tinbergen also found that for chicken, the same elongated cross-like shape, if moving in the direction of the long arm, is considered harmless (goose, perhaps), but if moving toward the short end, will immediately send them running for cover (hawk). Jorg-Peter Ewert found that the common toad Bofu bofu considers a stripe moving longitudinally as a prey; and a stripe moving sideways as predator. 9

kirkus reviews

A cognitive scientist synthesizes recent findings of vision researchers to unveil some of the secrets and explore still-unsolved puzzles of how we see. Hoffman (Univ. of Calif., Irvine) argues that children are born with innate rules of universal vision just as Noam Chomsky has argued for innate rules of universal grammar. These inborn rules of vision allow children to acquire, through visual experience, rules of visual processing by which the child constructs, in a multiplicity of stages, visual scenes. The first 20 of these roles, as spelled out here, have to do with seeing shapes. Rule 1, for example, is "Always interpret a straight line in an image as a straight line in 3D." Next are eight rules for color and seven rules for motion. These are illustrated with line drawings and photographs--120 in black-and-white and 30 in color--that draw the reader into participating in his demonstrations. The problem of showing motion is neatly solved by Hoffman: he directs readers to his Web site, where all the motion displays discussed here can be viewed. Like V.S. Ramachandran (Phantoms in the Brain, p. 1096), Hoffman draws on patients with pertinent brain anomalies to explain normal visual intelligence. Also like Ramachandran, he uses phantom limbs to explore briefly the sense of touch, for Hoffman is persuaded that the brain constructs not only what is seen, but also what is felt, heard, smelled, and tasted. He closes with a venture into the world of virtual reality that inspires a series of probing questions into the relationship between what we see relationally (i.e., what we interact with) and what we see phenomenally (i.e., what the visual intelligence constructs). With its many fascinating visual demonstrations, Hoffman's presentation fully engagesthe reader, demanding and rewarding attention. - kirkus

Contents

1. A Creative Genius for Vision 17 2. Inflating an Artist's Sketch 35 3. The Invisible Surface that Glows 68 4. Spontaneous Morphing 102 5. The Day Color Drained Away 130 6. When the World Stopped Moving 166 7. The Feel of a Phantom 198 8. Peeking Behind the Icons 211 blurb: In an informal style replete with illustrations, cognitive scientist Donald Hoffman presents the compelling scientific evidence for vision's constructive powers, and in so doing he unveils a grammar of vision - a set of rules that govern our perception of line, color, form, depth, and motion. Hoffman also describes the loss of these constructive powers in patients who have suffered devastating impairments: the artist who can no longer see or dream in color; the woman who, having lost her perception of motion, can no longer cross the street. Finally, Hoffman explores the spinoff of visual intelligence in the arts and technology from the dynamics of film special effects to the visual worlds of virtual reality.

amitabha mukerjee (mukerjee [at-symbol] gmail.com) 2011 Jul 04