Babur and Wheeler M. Thackston (tr.)

The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor

Babur [Babar]; Wheeler M. Thackston (tr.); Salman Rushdie (intro);

The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor

Oxford University Press, 1996 / Modern Library 2002, 554 pages

ISBN 0375761373

topics: | india-medieval | mughal | history | autobiography

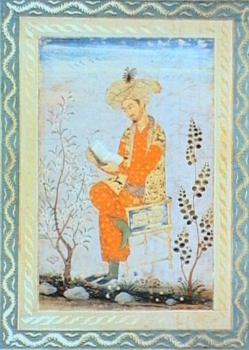

babur portrait - from a mughal period illustrated edition of baburnama.

Born into the minor kingdom of Fergana in strife-torn central Asia (modern Uzbekistan, bordering Kyrgyzstan), Babur went on to conquer a large swathe of South Asia and laid the foundations of the Mughal empire which was to last three centuries.

Babur became king at 12 (1494) when his father died while racing pigeons from a balcony that collapsed. His was a small kingdom in Andijan - today a major town at the easternmost border of Uzbekistan, some 1000km north of Kabul. Three years into his reign, he launched an expedition on Samarkand, but in his absence his own kingdom was usurped, and for many years, he lived as a wandering group, building up alliances. Later, after the technology of matchlock guns came to him from the Ottomans, Babur launched a successful invasion of India, defeating the army of Ibrahim Lodi at Panipat in 1526.

From his accession uutil his death four years after Panipat, he maintained a diary, parts of which he edited extensively in later years. Unfortunately, large chunks have gone missing, including the period of his conquests to India. The diary is written in a elegant style, and is widely considered a classic work of literature. Amitav Ghosh calls it "one of the true marvels of the medieval world. It belongs with that tiny handful of the world’s literary works that can accurately be described as unique: that is without precedent and without imitators." This is because in writing an autobiography, Babur broke new ground in the Mongol tradition. "What made him pen this immense book (382 folio pages in the original Turkish) and how on earth did he find the time? Between the moment when he gained his first kingdom at the age of 12 and his death 35 years later, there seems scarcely to have been a quiet day in Babur’s life."

Babur wrote in the language Chagatai (Chaghtai), a Turkic language named after Chagatai Khan, Genghis' second son. This was the language of a large part of the Mongol empire, the Chagatai Khanate (13th-15th c.). In the time of Babur, a literary form of the language developed among the learned elite in Samarkand and along the Silk Route. Extinct today, Chaghtai is the parent language for modern Kazakh and Uzbek. [The last speakers may have shifted to other languages during the Soviet era. ]

Babur was exposed to the literary traditions in Chaghtai, which he calls Turki, while staying in Herat, a center of Islamic learning. He became familiar with the poetry of Ali-Shir Nava'i (1441-1501), who popularized Chagatai as a literary language. They may have met, for Mir Ali composed some poets for Babur. In any event, Babur was well-versed in Chaghatai poetry, and would often recite poetry in his wine gatherings. This scholarly translation by Wheeler Thackston includes background material in the form of copious notes, maps etc. Thackston has also collated the text from several manuscripts, and related it to the well-known translation into Persian by Abdul Rahim Khan-Khanan (under Akbar). He has also translated a number of Persian texts including Rumi's Signs of the Unseen and Jahangirnama.illustrated page from baburnama, showing animals of india. [text is the Persian translation by Abdul Rahim, ca. 1590]

Excerpts

In the month of Ramadan in the year 899 [June 1494], in the province of Fergana, in my 12th year I became king. [opening line] [Babur then goes on to describe the Fergana valley region, south of the Syr Darya river], "on the edge of the civilized world." After his conquest of India, he often expresses his wonder at this new nation that he was now the overlord of. He marvels at the land: Compared to ours, it is another world. Its mountains, rivers, forests, and wildernesses, its villages and provinces, animals and plants, peoples and languages, even its rain and winds are altogether different. The cities and provinces of Hindustan are all unpleasant. All cities, all locales are alike. The gardens have no walls, and most places are flat as boards. He is not happy with the teeming crowds, and does not like the processes of agriculture. He does not like much of the food and animals. Some of his metaphors describing his displeasure can be quite dramatic: The parrot can be taught to talk, but unfortunately its voice is unpleasant and shrill as a piece of broken china dragged across a brass tray. However, occasionally he may find a good thing though not unmixed: When the mango is good it is really good [...] In fact, the mango is the best fruit in Hindustan. The tree is elegantly tall, but the trunk of the tree is ugly and ill shaped. 344

Letter to Humayun

Through God's grace you will defeat your enemies, take their territory,

and make your friends happy by overthrowing the foe. God willing, this

is your time to risk your life and wield your sword. Do not fail to

make the most of an opportunity that presents itself. Indolence and

luxury do not suit kingship.

Conquest tolerates not inaction; the world is his who hastens most.

When one is master one may rest from everything — except being king....

Item: In your letters you talk about being alone. Solitude is a flaw in

kingship, as has been said. "If you are fettered, resign yourself; but

if you are a lone rider, your reins are free." There is no bondage

like the bondage of kingship. In kingship it is improper to seek

solitude.

--

From fear and hardship we found release - new life, a new world we found.

111

I felt that I could endure no more. I rose and went to a corner of the

orchard. I thought to myself that whether one lived to a hundred of

a thousand, in the end one had to die. 137

For some years we have struggled, experienced difficulties, traversed long

distances, led the army, and cast ourselves and our soldiers into the dangers

of war and battle. . . . What compels us to throw away for no reason

at all the realms we have taken at such cost? Shall we go back to Kabul and

remain poverty-stricken? p.358

[blurb]: Both an official chronicle and the highly personal memoir of the

emperor Babur (1483–1530), The Baburnama presents a vivid and

extraordinarily detailed picture of life in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and

India during the late-fifteenth and early-sixteenth centuries. Babur's

honest and intimate chronicle is the first autobiography in Islamic

literature, written at a time when there was no historical precedent for a

personal narrative — now in a sparkling new translation by Islamic scholar

Wheeler Thackston. This Modern Library Paperback Classics edition includes

notes, indices, maps, and illustrations.

[inherent sense of destiny]

Since we had always had in mind to take Hindustan, we regarded as our own

territory the several areas [...] which had long been in the hands of the

Turk. We were determined to gaincontrol ourselves - be it by

force or peaceful means. 271

The next morning, at a wine party in this same garden, we drank until night,

and had a morning draught. While touring the harvest my companions who were

inclined to wine began to agitate for some. [...] We sat down under the

colorful trees and drank. The party continued there until late that night.

299

Thank goodness now everything is all right. I never knew how precious life

was. 374

If I die with good repute, it is well. I must have a good name, for the body

belongs to death. 384

ALSO: see this review by Sunil Sethi in the Business Standard.

bookexcerptise is maintained by a small group of editors. get in touch with us! bookexcerptise [at] gmail [dot] .com. This review by Amit Mukerjee was last updated on : 2015 Jul 24